A good life for all within planetary boundaries

If all people are to lead a good life within planetary boundaries, then our results suggest that provisioning systems must be fundamentally restructured to enable basic needs to be met at a much lower level of resource use.

Source: Nature Sustainability volume 1, pages 88–95 (2018)

doi:10.1038/s41893-018-0021-4

One of the authors has summarised the paper in The Conversation.

The data are also available via an interactive website (https://goodlife.leeds.ac.uk), which allows users to query the dataset, generate visualizations and produce ‘safe and just space’ plots

Excerpt from the Article:

A good life for all within planetary boundaries:

[…]

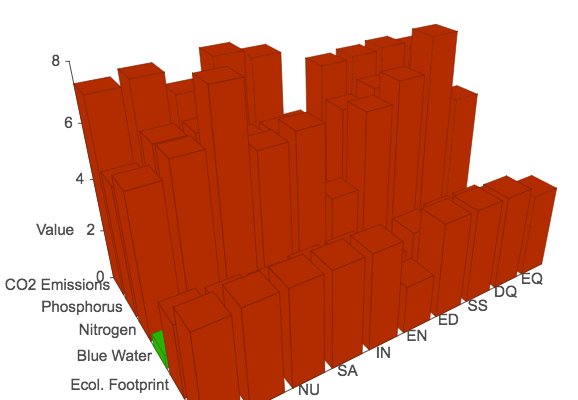

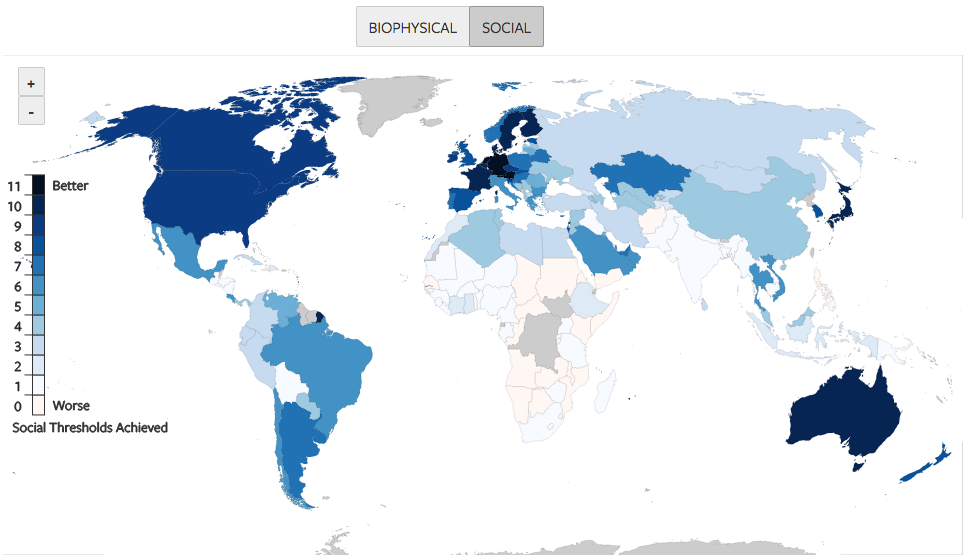

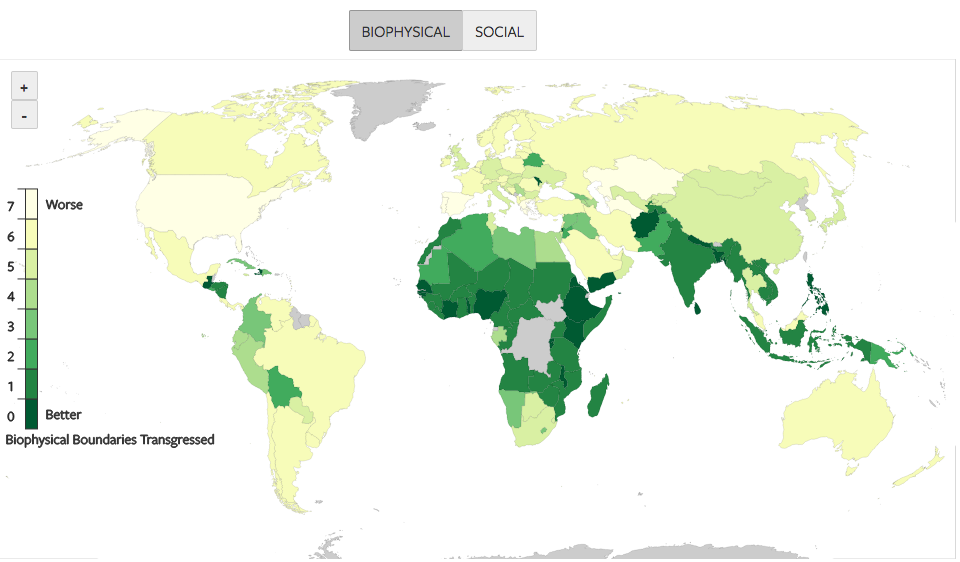

This Article addresses a key question in sustainability science: what level of biophysical resource use is associated with meeting people’s basic needs, and can this level of resource use be extended to all people without exceeding critical planetary boundaries? To answer this question, we analyse the relationships between 7 indicators of national environmental pressure (relative to biophysical boundaries) and 11 indicators of social outcomes (relative to sufficiency thresholds) for over 150 countries. Our study measures national performance using a ‘safe and just space’ framework1,2 for a large number of countries, and provides important findings on the relationships between resource use and human well-being.

[…]

Discussion

„These findings represent a substantial challenge to current development trajectories. Given that the United Nations ‘medium variant’ prediction is for global population to rise to 9.7 billion people by 2050, and 11.2 billion by 210041, the challenge will be even greater in future if efforts are not also made to stabilize global population. It is possible that the doughnut-shaped space envisaged by Raworth1,2 could be a vanishingly thin ring.

Physical needs (that is, nutrition, sanitation, access to energy and elimination of poverty below the US$1.90 line) could likely be met for 7 billion people at a level of resource use that does not significantly transgress planetary boundaries. However, if thresholds for the more qualitative goals (that is, life satisfaction, healthy life expectancy, secondary education, democratic quality, social support and equality) are to be universally met then provisioning systems—which mediate the relationship between resource use and social outcomes—must become two to six times more efficient.

Based on our findings, two broad strategies may help move nations closer to a safe and just space. The first is to focus on achieving ‘sufficiency’ in resource consumption. For most of the biophysical–social indicator pairs analysed in this study, each additional unit of resource use contributes less to social performance, particularly beyond the turning point where the estimated linear–logarithmic or saturation curves flatten out (Supplementary Table 3). Our results suggest resource use could be reduced significantly in many wealthy countries without affecting social outcomes, while also achieving a more equitable distribution among countries. A focus on sufficiency would involve recognizing that overconsumption burdens societies with a variety of social and environmental problems42, and moving beyond the pursuit of GDP growth to embrace new measures of progress43. It could also involve the pursuit of ‘degrowth’ in wealthy nations15, and the shift towards alternative economic models such as a steady-state economy24,44.

Second, there is a clear need to characterize and improve both physical and social provisioning systems. Physical improvements include switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy, producing products with longer lifetimes, reducing unnecessary waste, shifting from animal to crop products, and investing in new technologies5,29. Remaining within the 2 °C climate change boundary is a particular challenge, requiring the majority of energy generation to be decarbonized by 205045. While the cost of wind and solar energy is falling dramatically, which could lead to a major shift in infrastructure46, the fossil fuel industry remains remarkably resilient, subsidized, and still capable of tipping us over the limit47. Moreover, improvements in resource efficiency are unlikely to be enough on their own, in part because more efficient technologies tend to lower costs, freeing up money that is inevitably spent on additional consumption (the so-called rebound effect)48.

For this reason, improvements in social provisioning are also required, in particular to reduce income inequality and enhance social support. Both of these indicators are only weakly correlated with resource use in our analysis (Supplementary Table 3), but have a demonstrated positive effect on a broad range of social outcomes49,50. Given the high resource use associated with qualitative goals such as life satisfaction (Fig. 4), these goals may be better pursued using non-material means. The combined effects of a few social and institutional factors such as social support, generosity, freedom to make life choices and absence of corruption have been shown to explain a substantial amount of the variation in life satisfaction among countries49.

Overall, our findings suggest that the pursuit of universal human development, which is the ambition of the SDGs, has the potential to undermine the Earth-system processes upon which development ultimately depends. But this does not need to be the case. A more hopeful scenario would see the SDGs shift the agenda away from growth towards an economic model where the goal is sustainable and equitable human well-being. However, if all people are to lead a good life within planetary boundaries, then the level of resource use associated with meeting basic needs must be dramatically reduced.“

Source: Nature Sustainability volume 1, pages 88–95 (2018)

doi:10.1038/s41893-018-0021-4

Source Pictures: https://goodlife.leeds.ac.uk