Colloquium no. 3: Friday 27th February 2015, 18.00 at HEAD-Genève

“Exception is a comfortable situation, allowing elasticity and singularity in our daily work, in our daily institutional management and in our world view.” Lysianne Léchot, dean of Studies at Geneva University of Art and Design was clear in her welcome address: notions of exceptionalism are at the heart of art school and need to be rethought. “Exception can be precious when it comes to art and design: aesthetic beauties and intellectual strength are, in the very best examples, exceptional,” Léchot continued. “But exception can also be a pitfall. Especially in a public educational institution. When schools reproduce social, ethnic or gender inequalities in their daily work, in their daily management and in their world view, they should be criticised, and transformed, so as to match the democratic ambition of equal opportunity for all.”

If notions of being exceptional and therefore somehow outside or above society allow art schools to measure things with a different yardsticks and to be less transparent and less accountable, institutionalized exceptionalism is indeed a pitfall. Such art school exceptionalism undermines broader attempts to dismantle structural discrimination in tertiary education. As I see it, it inhibits the frequently invoked quest for “diversity” – the discovery of supposedly unexpected talent that can innovatively undermine the normative. Who determines who is, objectively speaking, exceptional and talented enough to be admitted into higher art education? How ‘objective’ are the supposedly objective selection criteria, when notions of who has “potential” and what potential looks like, tend to be inherently classed and racialized? What criteria can we establish to ensure that “the chosen few“ entering and completing art school come from a range of socio-economic and cultural backgrounds?

Some of these questions were discussed in the afternoon session preceding the public evening lecture evening (opened by Lysianne Léchot). The seven co-research groups, consisting of students and teachers from ZHdK, HEAD and HEM, discussed a preliminary booklet of recommendations on how to foster equality and plurality at art schools which has been compiled by Art.School.Differences. These recommendations set out the areas of conflict within the admissions process at the three schools. Among other things, they indicate the proportion of Swiss art students from migrant backgrounds, so-called ‘secondas’ and ‘secondos’, and highlight that, although gender considerations have been integrated into the admission process, they revolve around binary, hetero-normative understandings of gender; and thus ideas about the masculine or feminine characteristics of an applicant are made, without consideration of gender-queer or non-normative femininities. The recommendations also include concrete tools and criteria with which to further reflect on and make more transparent the processes of admission. The co-researchers especially welcomed the recommendation that all candidates, not least the rejected ones, should be given a feedback – even if they do not dare to ask for it. Institutional feedback would turn the admissions process into a learning experience, which is valuable especially to those who could not afford to attend foundation courses (propadeutika).

Public Lecture 1: Gender discrimination in French Art schools

Fabienne Dumont, École Européenne Supérieure d’Art de Bretagne EESAB, Quimper

Lecture 1 by Fabienne Dumont, 27.2., at HEAD.

The first evening lecture by Fabienne Dumont, art historian, art critique, and professor for contemporary art at the “école européenne supérieure d’art de Bretagne“ focused on the marginalization of women in art schools by comparing the under-representation of women in the French art world of the 1970s and of today. She analysed gender inequality in the 1970s by looking at the small percentage of women artists represented in art exhibitions, museums and magazines. She blamed the lack of female professors and directors at Art French schools for female art students‘ internalization of limitations. Nowadays, 60% of all art students in France and a third of all art school teachers and directors are female, and the percentage of women artists in exhibitions and at biennales in France has risen to 30%. However, the fact that the number has stagnated indicates that the glass ceiling is still intact.

Speaking of her work at an art school in a marginal region of France, where many students have a limited educational background and few of them go on to pursue professional artistic careers, Dumont suggested that the curriculum should be less narrowly oriented towards the contemporary art world. More open interactive educational formats need to be integrated, without, however, privileging the attendance of male students, who are still treated as the sole future breadwinners. Dumont doubted that the charter against discrimination, currently being developed at French Art schools (mostly in response to increasing numbers of students claims of sexism and sexual harassment), will bring much change. Given that a similar policy is already in place, Dumont proposed that anti-discriminatory laws should be accompanied by the creation of “listening spaces,” which include teaching staff and administrators. The fact that female students do not receive the best marks and are less encouraged to pursue careers as professional artists, could be rectified by augmenting the numbers of female art teachers to at least 40%. “Because even if these women are not feminists, the perception of the possibility of being female artist would become more widespread amongst students.” Dumont references the “Feminist Art Program” a collective of female art students and teachers in California who rejected the idea of male genius and worked towards developing artistic criteria that legitimated “practices related to the experiences of women.” In conclusion, however, Dumont held that these women-only initiatives have lost their appeal and cannot be replicated today, but that “we obviously need programs that teach gender, postcolonial or class in the curriculum, to legitimize aspirations for greater social justice.”

GenderDiscriminationInFrenchArtSchools_FabienneDumont

Discussion: As Dumont did not focus much on the practical implementation of her suggestions, for example, the idea of creating a “listening space,” she was asked to explain how exactly spaces of reflection could be fostered within today’s art schools. Dumont’s personal teaching practice of forming small groups of students interested in questions of gendered inequality and empowering them by broadening their horizon, did not seem to yield the basis for a broader conversation about how to foster critical discussions on norms and inequalities across schools. Dumont’s main suggestion of fighting gender discrimination by raising the number of “women” art professors was critiqued on the grounds that it reifies “women” as a seemingly static category, and did not account for intersecting categories such as race or class. Even if “counting men and women” seemed to be the easiest way to address the complexities of gender imbalances, such an approach was problematic if it reproduced a binary construction of gender and stabilized the unmarked position of white women. Rather than reifying a male-female division and thus rendering invisible non-normative gender identifications, it might be more fruitful, discussants argued, to raise the number of teachers who inhabit a variety of “minoritized positions”.

Public Lecture 2: Decolonising Art and Education through Creative Practice

Evan Ifekoya & Rudy Loewe, interdisciplinary visual and performance artists, London

Lecture 2 by Rudy Loewe and Evan Ifekoya, 27.2. at HEAD.

The twin-presentations by Evan Ifekoya and Rudy Loewe focused on their individual work and facilitation practices as artist-activists in London, exploring anti-racist and anti-sexist methodologies by “utilising archives, contemporary culture and lived experience.” Both Ifekoya and Loewe identify as non-binary persons and prefer the gender-neutral pronoun “they” (hence also: their, them) in lieu of he or she. Both are committed to working with and making visible the (archived) works of people of colour. And both are generous in sharing their projects and ideas online, even if “this might not be a good business plan.” They like the idea of being a resource to all – while being aware, however, that the internet is not accessible to everyone either.

Evan Ifekoya’s aim of decolonising artistic practice began with re-naming themselves: Rather than using the British surname of their Nigerian father, Evan took on their mother’s maiden name Ifekoya, a name that existed prior to the insertion of British names and colonial naming practices in West Africa.

Ifekoya is part of QTIPOC, a London-based group of Queer, Trans* and Intersex People Of Colour. QTIPOC meets on a monthly basis to foster collective forms of creativity and make visible the works and histories QTIPOC. http://qtipoccollectivecreativity.tumblr.com Their homepage says: “As a collective of QTPOC artists who have all in some way felt failed by the art academy and our formal educations, this project offers up a space to critically reflect on those experiences and examine the gaps and absences in art institutions.“

Ifekoya teaches art to children who have been excluded from “normal” schools. She also takes working-class youth and children into art galleries and museums. In a school workshop taught at the Tate Modern in 2013, Ifekoya made their own body into an art project. Incited by one of the pupils who questioned Ifekoya’s sex/gender identity, Ifekoya invited all pupils to ask the visitors of the Tate, to comment on Ifekoya’s body and identity. The responses were written on stickers and posted on Ifekoya’s body. The process amounted to a way of learning about the relativeness of categorization, while also putting at center-stage a black, gender-queer body within a colonial museum space. (The Tate was built on money gained during the transatlantic slave trade.)

“Artfunshack” Ifekoya’s colourful, weekly online art show, draws on pop culture images and uses tropes of childhood such as the legendary U.S. TV program “Sesame Street” to address, in particular, children of colour. In one video, for instance, they are making bounty balls, in reference to the Bounty Bar – a popular chocolate bar in the U.K. which consists of coconut covered in chocolate. A ‘bounty bar‘ or ‘coconut‘ is also a derogatory term for a person of colour who does not conform to internalised stereotypical ideas about how a person of African or Asian decent is supposed to behave, and is thus criticised for being “white on the inside and brown on the outside,” Ifekoya’s “compulsory visibility” as black and gender-queer body, emerges as an important starting point for their playful work around questions of identity and authenticity and their search for utopian spaces.

Rudy Loewe is a visual artist, educator and storyteller who works primarily in comic and zine format. Lead by an autobiographical focus, Loewe addresses issues concerning gender, race, sexuality, trauma, and mental health.

Loewe’s prints and comics speak about “bad therapy” and about trying to access mental health services in London. They represent traumatic experiences of domestic violence and abuse through a child’s eyes , and they evoke sudden falls and accidents as pivotal moments in our lives. The latter comic, on “free falling,” explores the tension between being in a constant state of flux and fall, while having to be tough and compelled to compartmentalize psychological things in order to survive economically and emotionally. Loewe’s take on “free falling” ties in with an interest in how everyday uncertainties and physical trauma are passed down to us generation for generation, from mothers to daughters. Loewe’s focus on the impact of (mental) health issues on the lives of people of colour draws attention to the bodily impact of structural discrimination.

Trying to escape the black-white logic, Loewe “brown washes” their work. Instead of working in black and white, Loewe uses brown paper and brown colours, in order to make brown people central to their stories. As educator and facilitator, Loewe often works in public libraries with working class black and brown kids. Loewe seeks to cultivate a space in which children, who may not consider their experiences important, begin to explore their own narratives. Conversations that touch on gendered and bodily experiences are part of these sessions. While queerness and sexuality is only addressed indirectly, many conversations with black boys revolve around being “stopped and searched” by the police.

Finally, Loewe talks about their interest in making archives accessible. Loewe was commissioned to make a comic on the late black modernist artist Claude McKay, a radical queer socialist who had some fame in the 1920s but was then largely forgotten again. By highlighting and reinvigorating different parts of McKay’s subjectivity, Loewe seeks to work against the marginalization of black artists and muses who “disappear” again, as they do not seem to be part of a larger tradition or not known to young artists of colour.

Discussion: Though Loewe and Ifekoya work mostly with kids and youth outside higher art schools, their intersectional practices could be considered a response to Dumont’s paper. While Dumont’s quest to contest gender discrimination at art schools, centers around the figure of the “woman” professor, in Loewe’s and Ifekoya’s teaching practice, gender is inextricably intertwined with conversations about race and sexuality. These issues are brought into conversations by using their own bodies to interrupt ideas of what constitutes the sexual and gender identity of a black/racialized person and by prompting pupils and arts teachers to rethink preconceived notions of masculinity and femininity.

The question, however, arises to what extent they can protect themselves from the unwanted attention their openness might trigger. Making their bodies and their traumatic experiences the site for instigating conversations on mental health and on what it means “be othered,” requires certain measures of self-protection. Their work implies a weaving in and out of art, academia and community spaces and requires a constant contending with the position of being simultaneously an insider and an outsider.

Public Displays of Accountability: Addressing Race in the Arts / Curriculum

Workshop by Evan Ifekoya and Rudy Loewe

Workshop by Rudy Loewe and Evan Ifekoya, 28.2., at HEAD

Saturday 28th February, 9.00 at HEAD:

The workshop elaborated on the issues Rudy Loewe and Evan Ifekoya raised in their lecture the previous evening. Besides introducing contemporary arts projects that challenge institutional frameworks (the links to these projects are listed in their Power Point Presentation: PublicDisplaysOfAccountability_Loewe_Ifekoya), the focus was on practical tools for addressing race and racism and on decolonizing art school teaching practices. Drawing on African-American feminist scholars and activists bell hooks and Audre Lorde, Loewe and Ifekoya advocated “the dismantling of the master house” in the art school curriculum, and hence the undermining of the “whiteness and hetero-patriarchy” of the curriculum. This implies not only engaging black teachers and professors, but teaching the writings of postcolonial scholars as part and parcel of the art school curriculum.

In terms of developing a radical pedagogy, Loewe and Ifekoya themselves have been inspired by texts such as Paulo Freire’s “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” and bell hooks’ books “Teaching Community: A Pedgagy of Hope” and “Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom.” hooks thinks through “how we are as bodies” in the learning/teaching environment and focuses specifically on the ways in which we navigate the spaces we enter as learner and/or and facilitators.

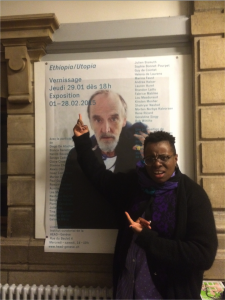

The core theme of the session was accountability. “By accountability we are referring to the process by which actions and language can be questioned in a non confrontational way.” While the workshop participants did not raise any issues that might need to be addressed, Loewe and Ifekoya tested our capacity to have non-confrontational conversations by speaking about their unease upon entering the HEAD and being confronted with two posters that offended them. One of the posters advertised an art exhibition entitled Utopia/Ethiopia. Yet, none of the artists listed seemed to be of Ethiopian background or to work on Ethiopian art. Rather the poster featured a grey-haired white man, thus reproducing the white male gaze that tends to “other” subject positions such as the ones inhabited by Ifekoya or Loewe. The other poster, in black and white, featured the sentence “JE SUIS CHARLIE.” Although a comic artist herself, Loewe could not identify with the practices of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. In fact Loewe felt hurt by the magazine’s “very violent, racist, sexist and islamophobic content” contributed to “violence against people of colour on the street.” Loewe’s and Ifekoya’s statements triggered a discussion about the degree to which it is possible to critique the position of Charlie Hebdo subsequent to the attacks in Paris within the context of a Swiss French art school. It was observed that counter-discourses and positionings, such as “Je suis Ahmed” (Ahmed, was one of the policemen killed in the event) had only little exposure at the HEAD and appeared to be almost unspeakable.

In the final section participants were invited to give a visual response to the session by producing their own zine, addressing the question: What would an accountability process look like?

By Serena O. Dankwa

Work in progress: Co-research projects of Art.School.Differences at the 3rd colloquium

The Saturday afternoon of this 3rd colloquium was fully dedicated to the seven Art.School.Differences co-research projects. Carmen Mörsch, who supervised the working session, emphasized a joint, collective and friendly, but critical questioning by the audience of each group’s presentation of their work in progress. This, on one hand, to give space to the potential arising out of the multitude of different experiences, disciplinary and working perspectives present at the colloquium, as well as, on the other, to allow questions and uncertainties of each research-group to emerge and to be addressed.

The group from Art Education at ZHdK led by Lorenz Bachofner, Laura Ferrara, Julia Kuster and Nora Schiedt focuses on the important, but contradictory role of «one’s own artistic / creative expression» in (higher) art education. On one hand, this idea is strongly related to problematic notions of talent or the genius (as well as the creatio ex nihilo). On the other, it reflects the widespread conviction that the artistic expression can be taught and learned in school. Drawing on their experience at the ZHdK, they explain that this claim was and still is not met within their own education, and go on arguing that the concept of the ‹singularity› tends to be a «Leerformel» in the sense of Ernst Topitsch. Furthermore, their research project mirrors their personal interest to break the «circle of reproduction» as they themselves are coming from high school and returning there after their studies as teachers. Methodologically, they aim at looking at the curricula («Lehrpläne») of three different high schools in the canton of Zurich and to conduct in-depth interviews with teachers while the latter are assessing their pupils’ artistic works. Possible research questions are the following: What effects do these curricula have on the individual teachers? How do teachers deal with it in their classes? How do they value work? And how do they speak about a student’s work while assessing it?

The research group from Fine Arts at ZHdK led by Romy Rüegger and Yvonne Wilhelm is interested in the question of what happens during the mentoring of a student by a teacher. These mentoring situations are of overall importance within fine arts education as working processes are individualized and have to be adapted to the interaction between teachers and students. Although this format opens up spaces for transgression and bears the overcoming of gridlocked structures inherent to teaching, it entails important moments of normativity as well as inclusion and exclusion. The research wants to address these by questioning the importance given to certain artistic values or references and canons. It also inquires the perspectives and positions taken on by speakers and how they reflect privileges. They started to collect and document research materials on an internal blog with students. To be able to overcome the challenge of their institutional positions as teachers, Romy Rüegger and Yvonne Wilhelm chose to stage a mentoring situation with students from the MA Fine Arts and from BA Kunst & Medien program and alumni at ZHdK (Onur Akyol, Martina Baldinger, Angelo Brem, Berivan Güngör, Bleta Jahaj, Patrick Kull, Rina von Burg). Some of them will take on the respective role as students and teachers while being observed by the others. Their experience and observations will be compared to the ones by the teachers themselves. The goal is to think of and establish other kinds of mentoring formats without them having to be new. While presenting their project, Romy Rüegger and Yvonne Wilhelm recalled the students group to first have been surprised about the idea of questioning the mentoring process. This suggests a strong expectation from the students that their mentors should define this situation instead of themselves. The example very well illustrates how the hierarchy of the teacher – student at art school is internalized and is reinforced in every day practice of teaching and learning.

Sarah Owen with Tingshan Cavelti and Allaina Venema from the design department at ZHdK, are researching the representations of the «ideal designer» in the educational system as well as «on the market»: Preferred are white, male, heterosexual and preferably Swiss, if not then Dutch or British subjectivities. Although abstract criteria are set up during the admission process, ideal types of designers are very prevalent. Among others, there is the maverick («Abenteurer»), lonesome wolf type, opposed to the bureaucratic designer («Gestaltungsbürokrat») type. Although both constructed ideal types differ in their narrative as well as visual representation, they nevertheless have something in common, as was pointed out in the discussion: both know the specific ‹traditions› of the design field very well: Even the one who aims to break the rules, has to know the rules beforehand. The group aims to work on questions that are interwoven with design education in Switzerland and beyond, also looking into the system of design education that is evaluated by the SERI (State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation) and peer reviewed every 5 years. Leading questions are: What does a designer need to know – and need to learn in order to be successful? The methodology consists in recording events and situations from everyday teaching and learning practices in which these or diverging representations of the «ideal designer» are articulated and reproduced, but also subverted. Their aim lies in constructing a sort of «counter-mythical person» in order to disrupt the relationship between a piece of work and its author.

Daniel Zea with Hyunji Lee and Andrea Nucamendi from HEAD-Genève have put their research focus on inequalities that foreign students encounter during their studies at the HEAD-Genève. They chose to especially emphasize non-European communities, as they seem to be particularly exposed. So far, they have identified a range of realms that impact equity and which they would like to touch on more in depth: Money, papers, language, artistic and conceptual references, discrimination and lack of technical lessons. As their group is composed of two foreign art students, one from Mexico and one from Korea, and is led by a Colombian teacher, their idea is to «get in contact with the subject of study, by the subjects being studied». They want to document all these inequities in video, photographs and sound recordings, in order to create a collection of material that forms an «artistic case-study» talking to students as well as teachers. Thereby, the emphasis is on how inequalities make students feel. As a final result, the group imagines an artistic piece that can have the form of a film, or an installation, or even a performance.

Martine Anderfuhren, Patricio André, Claire Bonnet, Fabio Fernandes Da Cruz and Ivan Gulizia from visual communication at HEAD-Genève are planning a series of events that, as a result, include the Otherness of students – the motto being «what you are reinforces your creativity». As a final result, their Otherness should be included into their course work and rendered productive on an overall basis instead of hampering. The planned events will at first be conducted within their own department of visual communication, such as an organizing of shared meals or quiz etc. These will enable exchanging on different professional developments, and on cultural and technical knowledge. In order for these exchanges to be fruitful, they propose to first make mini-events to create «godparent» relationships among all the students and teachers. The first of these mini-events has been planned in detail and will be announced by a «fire alarm». As they argue, it will allow for their project to start within a humoristic ambiance, as well as to have the entire school present on the same spot and to initiate the godparent relationships. However, they will keep the secret on further events and just give the advice to people that they should keep in touch with their godparents and godchildren, suggesting its helpfulness for the future. The first event is to take place mid of may.

Patrik Dasen with Soojin Lee from HEM Genève are leading a research amongst non-European students of the school with the aim of highlighting their socio-cultural and socio-economic background and current situation of studying in Geneva. This project, thus, evaluates both the music students potential needs in terms of a better integration in the general life of the institution and the potential socio-cultural added value each foreign student is, or can be, for the institution. In terms of methodology, the group first works on the a priori representation of music and students among students as well as reflected by the school, questioning Western traditional music and its symbolic power, as well as the economical, social and cultural students’ background, etc. They will conduct semi-directive interviews, starting with a few preliminary interviews with informants to establish the interview guideline. Second, they will also look into the effects of the relationship between interviewers and interviewees to reflect power relations inherent to the interview situation.

The team of Victor Cordero, Bernardo Di Marco and Micha Seidenberg works on the theoretical knowledge of music from the perspective of non-European students. Having an eliminatory function if not passed within the admissions’ process, the test of musical theory has exclusionary effects for specific student groups. It is actually highly based on competences acquired before the entry at the high school. Being given that the HEM wishes to integrate international students and thus students with a quite different knowledge from those built by the school of musical theory in Europe, a conflict of interest emerges that is the object of the research lead by this group. In order to prepare interviews with students and teachers, they are looking into the statistics made by the school for the admissions process, on, for example, the nationalities of the candidates – accepted and non-accepted – and other information gathered every year by the HEM. They also already have contacted students from non-European countries in order to exchange with them to know more about their relation to theory of music and the way it is taught at the HEM.

By Philippe Saner, Pauline Vessely, and Sophie Vögele