Blog entry on Art.School.Differences: bit.ly/a_s_d; 31.10.2017

Paola De Martin,

—

“I really don‘t like words like ‘artist’, or ‘integrity’ or ‘courage’ or ‘nobility’. I have a kind of distrust of all these words, because I don’t really know what they mean, any more than I really know what such words as ‘democracy’ or ‘peace’ or ‘pace-loving’ or ‘warlike’ or ‘integration’ mean. […] The terrible thing is that the reality behind these words depends ultimately on what the human being (meaning every single one of us) believes to be real. The terrible thing is that the reality behind all these words depends on choices one has got to make, for ever and ever and ever, every day.” (James Baldwin)

—

Introduction

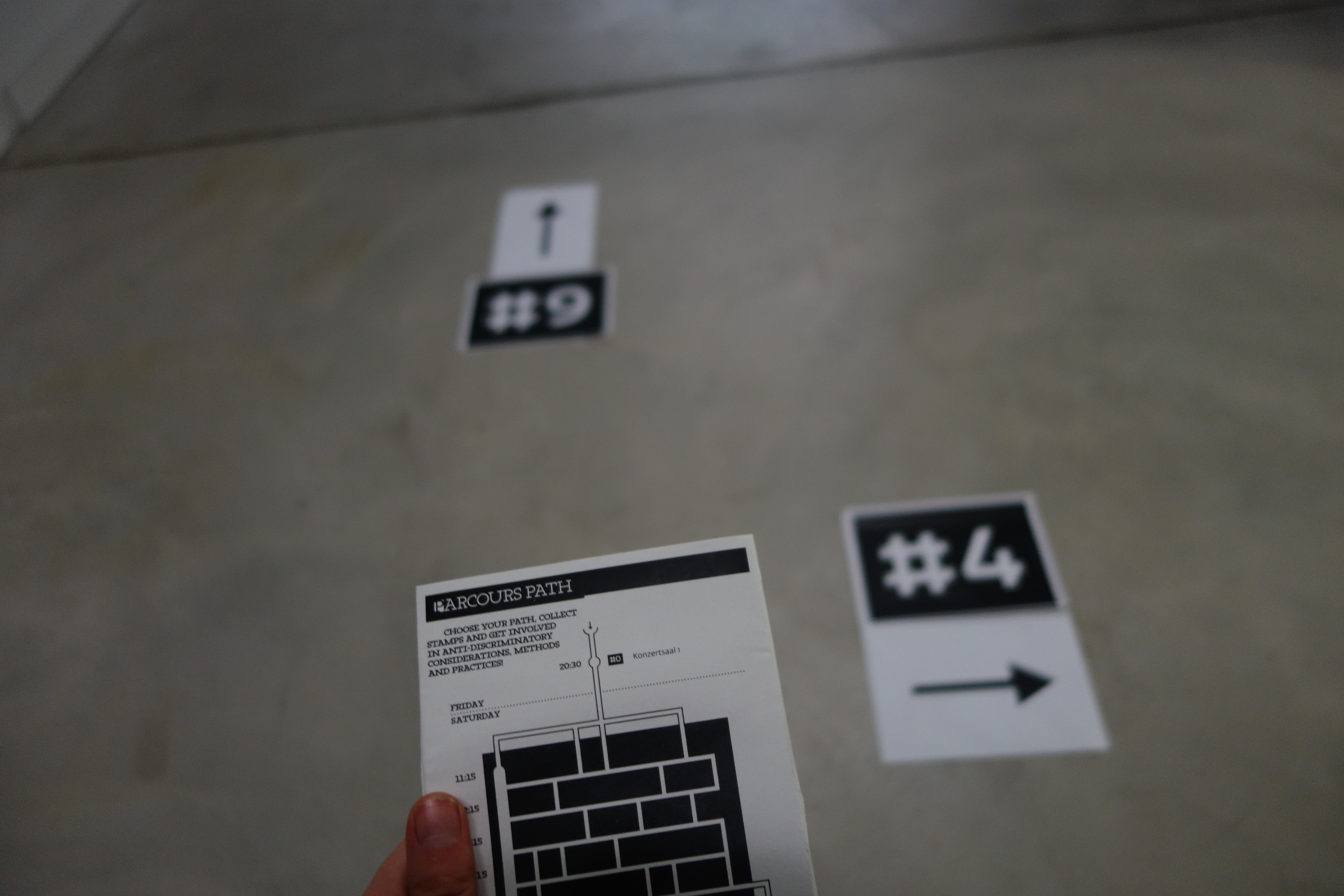

In November 2016 I was invited to hold a workshop (for the description refer to PARCOURS) for the Final Symposium of Art.School.Differences Because it’s 2016. Challenging inclusion and exclusion at Swiss art schools. I presented and worked with material from my ongoing PhD-research (run-time: Sept. 2014–2019). For this workshop I emphazised the epistemic phenomenon I call “a double-quoted world”. The title of my PhD-research is Give us a break! On the taste-biography of designers featuring a working class background in metropolitan Zurich (1970–2010). Interviews with designers are the primary oral sources of my work – designers form different subfields of design, born between the late 1940s and the early 1990s. Some have the Swiss passport, some don’t, but that’s not the main question here, neither the difference made by sex, gender and race. Although my intersectional analysis does take different axes of discrimination into account, my interest focuses on what the interviewees have in common: a pronounced social upward mobility from the lower classes of society into the field of design. I combine the oral sources with visual material mentioned in the interviews or handed out to me by the interviewees. The centre of my interest is the question: What does it mean to become a designer, when socialized in the working classes during the era of neo-liberalism in Zurich? This includes also asking: what does this mean to me – since I feature this “background” too – ? I put “background” between double-quotes, because I actually don’t like to use the term in my context so much anymore. As I realized during the research process and will show below, former working class cultures and spaces are an important source of inspiration for designers, and for this reason working class attitudes morphed into a stunning present of our designed “foreground”. How can you possibly get along within this transformation when moving upward form the working classes? In what ways can you possibly move upward? How can these possibilities be described objectively, i.e. without mystifying these paths?

In my analysis, the collected oral histories function like special lenses that allow us to answer these questions and to understand the overwhelming aesthetic impact of social life. The phenomenon of “a double-quoted world” shows how designers with working class background deconstruct categories of aesthetic quality, such as “formalism”, “reductionism”, “functionalism”, etc. The common sense of good taste takes these categories as universal, and not as socially bound ones. Two dimensions of my analytical compass turned out to be useful, when arguing against the common sense of universalism in good taste. First, the historical, diachronic dimension, i.e. the continuities and discontinuities in the relationship between the milieus of the working classes and the field of design. Second, the sociological, synchronous dimension: i.e. the quality of this relationship in our post-modern, neoliberal or globalized present. Both dimensions are also interwoven in this blog entry. Now, before addressing the topic of my workshop, I will first provide an outline of my research in which it is situated.

Neo-liberalism, the working classes and the field of design in Zurich

Since the late 1970s Zurich’s social structure has undergone a massive change. In this respect, Zurich, the hot spot of my local case study, is comparable to other cities. When presenting my research in an international context, I often hear similar stories like the ones I present here, from London, Izmir, Copenhagen, Toronto, Warsaw, New York or even Ahmedabad and Saigon. What characterizes the change is first the decline of huge productive infrastructures of material labour – in Zurich for example the machine construction industries in the neighbourhood of Zurich-Oerlikon, the industrial milk production factories, the turbine and the detergent industries in the Zurich Industriequartier, the textile industry in Zurich Altstetten, the huge beer industry at Zurich’s riverside of the Limmat, the industrial paper mills at Zurich’s riverside of the Sihl – and second the gentrification of these areas, their social cleansing and takeover by what is called “immaterial labour” (Lazzarato, 1996). Zurich, coined “Rotes Zurich” – meaning the “red city” of the interwar period, a former socialist city with a strong worker’s presence and representation rooted in the socialist movement – is now well known as a centre for finance, higher education, insurance, IT and art & design with international reputation. Social democrats and the green party are representing the majority of the voters in the city’s executive, but their red-green rule is almost completely middle class based today. In the meantime, also the student body of the art & design school has changed. The former Kunstgewerbeschule deliberately attracted worker’s and craftsmen’s sons during the interwar period (not so much daughters, then) – I thereby think of iconic figures like Gottfried Honegger or Richard Paul Lohse. During the Cold War and the golden decades of Keynesian welfare, the school was still quite open to descendants of the skilled workers or craftsmen, such as Willy Guhl or Franco Clivio, for example. Today, due to Bologna reforms and the academization of the Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK) – merger of the major branches of the Zurich educational art institutions since 2007 – the student body of the design department has become similar to the one of the humanities in Swiss universities, such as the University of Zurich. It is dominated by middle or upper middle class adherents, whose parents are well appointed with cultural capital. The loss of talent and potential on the paths from lower classes to higher education is diagnosed by social historians and sociologists as the effect of manifold practices of discrimination that upward-movers must encounter along their way; the metaphor of a “leaky pipeline” is used to illustrate this. There is quite a wide range of scholarly work about this effect. In Switzerland, especially Margrit Stamm’s research stands out (Stamm 2016). None of the studies, whatsoever, look closer at the field of design in Switzerland, with the outstanding exception of the Art.School.Differences project.

And what does it mean to become a designer, when socialized in a working class that has almost disappeared? What did it mean for me? When studying textile design in the 1990s at the Schule für Gestaltung Zurich (today: ZHdK) and even more when being a practitioner, I was first overwhelmed by the way my professors and my peers embraced the new empty post-industrial spaces, by how they turned them quickly and enthusiastically into studios, party locations, art spaces and lofts. Born 1965, I rank among a generation that still can recur to the memory of tattoos, soccer, boxing, bodybuilding, big cars, bling-bling, pop-music, precarious work, physical production inside industrial spaces, transgressive styles and sexually overemphasized attitudes as solely belonging to the lower classes. This radically changed during the late 1980s and early 1990s. I was electrified by the general playfulness and productivity in adopting former modes of lifestyle from the workers, be it in a more sublime or in a more carnivalesque way.

But I also was irritated: Why where designers making fun of the poor? Why where they making poor cultures more sublime, as if poor peoples were the raw material for the real virtue of style? What was so great about this dirty emptiness, this sudden silence of the machine age? What would all the unskilled people do for a living, when all these industries disappeared? So, very soon, my bewilderment mutated into confusion, and confusion into an intangible shame about my real worker’s child past. The French intellectual and sociologist Didier Eribon, in his wonderful sociological self-analysis Retour à Reims calls this kind of shame “social shame” because of its rather political than psychological implications. Being a worker’s child himself and gay, Eribon highlights the fact that in the era of neo-liberalism it was so much easier for him to reject in public the imposition of his sexual than of his “social shame” (Eribon 2016, 19–20). Both deal with the limitations of normativity, one with the heterosexual and the other with the middle class normativity, but the latter is so much less discussed and debated – maybe because it is a new phenomenon we still have to reflect? I can say for sure that in Zurich from the late 1970s on I began to feel my lower class past becoming the loser’s past. But this was an incredibly quick and complex transformation, too tricky to keep up consciously since I was merely a child and teenager then. Talking with Karl Marx, I was „alienated“ from the historical context that shaped my shame (Marx 1957ff., vol. 3, 72 and vol. 40, 512). To survive the changes I displaced the consciousness for being conceived as a neoliberal loser. I displaced the same consciousness for my parents and their friends, and the children of their friends. That was not as bad as it may sound, alienation can be very dazzling. In fact, only today I can see clearly that I was yet very much attracted by the dazzling field of design because of its alienating, illusionary and ahistorical aura.

“Illusio” and other useful terms – a brief excurse into sociology and Zurich’s design scene

The terms “rupture“, “habitus”, “illusio“ etc., that I like to use, are sociological terms, coined first by Pierre Bourdieu and adapted from other scholars ever since, to whom I owe my greatest respect. They helped me to understand the deep political and historical implication of my “social shame” in the design field. A short explanation of these terms situated in the context of Zurich might help the readers, too.

“Illusio“ after Pierre Bourdieu means the faith in the reality of the game you are playing in a very specific professional “field”. Every “field”, e.g. “the field of education”, “the field of the arts”, “the field of science” or the “field of economy” etc., creates its own “illusio”. “Illusio” therefore is the faith or belief that the inputs and outputs of what is at stake are of value (Bourdieu 1996, especially 330–336). For the field of design – or, more precisely, the subfield of design in the greater field of the arts – the “illusio” creates the deep belief that what talented designers really do are beautiful, meaningful and functioning things, and that it is really worth putting all your skills and ambitions to reach this aim. Bourdieu’s concept of “illusio” is helpful to investigate the sober facts behind it. Only then you see how the social structure of inequality within the field is being shaped – beyond the veil, so to speak, of all agents. Inside the field of design and beyond the veil of its “illusio” lies the sober fact that what talented designers do are status objects – and status knowledge of Swiss society is therefore the crucial knowledge for a successful designer in Zurich.

Because the recognition of this factual reality behind the veil would somehow spoil the “illusio”, it must be displaced. But how is this displacement working, and why is it working so well? On a general level, these questions were the driving force behind all endeavours of Bourdieu’s sociology. One of my students once said, after reading Bourdieu in my class, that talking explicitly about the making of status with designers is like talking about what you do while you are seducing somebody. Following her striking remark, one could say that designers are trained to make status differences look sexy. To understand how and why the displacement of status knowledge is working so well, and in Zurich’s design scene it is working extremely well, the concept of “habitus” is helpful. “Habitus” is a set of practices and judgements that are conceived by the common sense to be quite natural. For example, one of the experts of the field, I also interviewed, said that it seems quite natural that a working class child would never become a designer. This naturalization is the effect of a forgotten history under the practical shortage of everyday life, a history that is full of status angst, social struggles and power games. Instead of being outspoken and part of the common design narration in Zurich, these histories are embodied, passed over by attitudes and judgements, performed and re-enacted by the uses of language and by institutional rules from generation to generation – without reflection.

A “rupture“ or “break” in sociological terms defines a moment in life, when specific strategies that you have internalized as a child and teenager in your milieu – your quasi-natural “habitus” – all of a sudden become disfunctional under other circumstances. This “rupture” can be caused by a change of the milieu and/or by a historical change of the social structure as a whole. My interviewees experience both. In fact, I found that they are “rupture” experts after making the effort to understand their statements hidden behind the narrow social limits of their speech. A “rupture” or “break” in this context doesn’t mean a physical or psychological trauma, but rather an epistemic shock. The social world doesn’t make sense in a natural way anymore, it becomes, as the title of my workshop indicates, “a double-quoted world”. It is within these “ruptures” that the forgotten histories of the social struggles in the field of design come to the surface. Some of them are very old, and date back to imperialism of free trade in the 19th century and to World War I. Some of them are younger, they relate our conflicts today to the Great Depression of the 1930s, to World War II, to the Cold War or to the economic crisis of the 1970s. I go into more detail in my dissertation and try to unveil the strong impact that these conflicts have had inside the field of design when it comes to its relationship to the working classes.

It is important to highlight that experiencing an epistemic “rupture” or “break” per se isn’t necessarily a negative experience. Social movements explicitly induce epistemic “breaks”. The feminist critique of “phallo-centrism“, the queer critique of “hetero-normativity“, the postcolonial critique of “euro-centrism“ and “white normativity” – in a very powerful and politically public manner – deconstruct the “illusio” of a naturalized social order. By doing so, they upset the deep faith of the patriarchal, heterosexual, white and western hegemony in culture. But how about class in culture, especially in the design culture of Zurich?

Seeking for appeasement – believing in design

To experience the shock of a “rupture” in a productive way it takes, first of all, reflexivity and then the support of peer groups, for this reason I call my dissertation project Give us a break! It is the attempt to regain the lost public space and the lost public terms of social thinking. I lost my peer group during the late 1970s and the 1980s when I went to high school, the first one in my family since generations and the only one of my whole working class neighbourhood. I also lost reflexivity because of the tensions that were threatening my parents, my sister and my whole milieu during the structural changes in Zurich, as I mentioned above. Today, I can clearly see that I wanted to believe in the “illusio” of the design world because it looked to me as if it was a safe realm – completely untouched by social tensions. I desperately wanted to escape from the harsh violence of the ongoing changes, and my skills and diligence allowed me to enter the world of creativity, of constructive talent and beauty as it was displayed to me in the design school: a wonderful, unspoiled, eternal and magic sphere. Religious connotations are obvious here. I believed in the universal embrace of good taste, in the complete modesty of modernist reductionism, in the unlimited longevity of sustainable design, in the ideologically boundless release given by post-modern irony, in the total approval of transgression by trash, in the socially infinite inclusion of kitsch by its campy sophistication, in craft as the truly unspoiled reference for industrious creativity, in the absolute rule of talent as the only legitimate means for success – and by doing so I learned in an absent-minded way to disdain my former working class self. But that is not all I did. In the context of neo-liberalism and postmodernism it is important to say that I also adapted myself unconsciously to a new symbolic competitiveness and scooped a most valuable resource to make ends meet: my insight into the intimate dreams of the wannabes. I did my part to provide the former industrial spaces with commodified phantoms of my own recent past.

Of course I felt that on the long run something was going terribly wrong, but I displaced this knowledge to keep going. After all, I had put so much time, energy and money to get there. Under these circumstances, being a design student with a strong connection to friends and families of my working class milieu, and even more being a practitioner was a long intensifying nightmare. A nightmare, speaking with Sigmund Freud, is not so much a horrible dream because of its horrible content, in fact, it is a horrible dream because the dream-work does not work and the truth about your wishes cannot be displaced and distorted anymore in order to keep sleeping (Freud, 1999, 578–592 and 688). Finally, this truth came through and made me wake up from somnambulism – it showed its naked face to the conscious mind, sometime around 2001: I had wanted to believe the “illusio” to stay inside the field, I had desperately embodied the role of the wannabe to stay inside, at any price – be it social self-disdain, be it economical and symbolic self-exploitation.

Waking up caused a severe epistemic and social “break” with the realm of design. The years before I had been back and forth in the process of awareness building about the “illusio” of the design scene, but once I allowed myself to see and reflect it, the whole design scene was definitely disenchanted. The universality of good taste became a double-quoted “universality“, modernist reductionism became only “so to speak modest“, sustainable design “pseudo long-lived“ and so on, but most important: the absolute rule of talent as the only legitimate means for success became a very relative and arbitrary rule. In other words, my new sobriety opened the view to highly distinctive, but seemingly invisible class-bound practices and class-bound judgements inside the design field.

This sober gaze was first a shock and became only fruitful with the further steps I took: my studies in economic and social history and art history at the University of Zurich and my dissertation supported by the ETH Zurich. When talking to the designers that are still in the field I am very much aware that my outside position is a now privileged one. Due to my distance as a scholar and to my sense for the special sound of the former worker’s dreams and nightmares inside the design field, I can crystalize class limits that insiders often cannot, even if they wanted. I am confronted with reflexion as well as with the limits of reflexion in the interviews, limits that may seem individually motivated. When considering the existential threat that a disenchanted awareness of the game can be for these agents, I see the limits of speech as manifestations of the narrow limits of open debates about class boundaries inside the field. Thus, I would follow Pierre Bourdieu who says that the practical, physical sense for social borders lends itself to the oblivion of limits (Bourdieu 2010, and 1987, 734). He is pointing out the fact that worker’s children eliminate themselves from highly skilled professions, because they don’t even think that these professions could be suitable for them. All my interviewees talk about the time it took them to overcome this inner gap. Numbers and statistics clearly show the quantitative surface of this habitual self-limitation in Zurich’s design field (Seefranz and Saner 2012; Saner, Vögele, and Vessely 2016). But what happens when you succeed in trespassing the line, despite of everything?

Disappearing behind the middle class mask

The practical sense of one’s place in society makes it seem quite natural that a working class child would not become a designer, like a cat, quite naturally, would not want to swim. So, once you made it nevertheless, things get very tricky. The practical, physical sense for social borders lends itself to the oblivion of limits – but only as long as you stay within the milieus of the working class and reproduce the status of your milieu in your own path. Trespassing the lines therefore means two things. First, that the oblivion is suddenly toothless and you start feeling the limitations offhand, struggling with an unknown sense of morbid strangeness. Second, that you experience the annihilating power of a middle class normativity: you do feel clearly out of place but realize that this out-placed position of yours, in the mind of everybody else accessing the field, does not exist. What does not exist cannot be recognised. This lack of recognition is the external contribution that completes the overall oblivion that trespassers overcome involuntarily. The lack of recognition from inside the field is another interesting thing. Here, once again, one could think that it is a personal attitude of some individuals that are just intellectually too lazy or not emphatic enough. Again, I rather suggest that it is a manifest articulation of the narrow limits of open debates about class boundaries, one coming from inside the field. By reading these articulations against the grain, the objective limits can be named and crystalized. Actually, a chapter of my dissertation is dedicated to the limitations in understanding my research by those who cannot possibly see the middle class normativity from within, like a fish cannot possibly feel the water, or: their own naturalized “middle class habitus” within a “middle class field”.

The denial of the existence of class boundaries inside the design field leads to a complex situation: an embedded loneliness of the “space intruders”, as Sara Ahmed calls social trespassers of all kinds (Ahmed, 2004). What is striking in all my interviews, is the fact that the interviewees are, simultaneously, completely fascinated by the “illusio” of the field, as much as they are forced to experience a “rupture” or “break” with the “illusio” that nobody else must. All of them use at some point the metaphor of a “dry sponge absorbing water” of the design world. And all of them tell me about their isolation, sometimes using positive visualizations such as “floating island”, “martian”, “hermit” or a James Bond-like “secret agent”, sometimes recurring to rather violent connotations such as “prisoner” or “hostage”. In their pronounced isolation it becomes clear that the working class intruders into Zurich’s design field cannot recognize so easily who is also wearing a middle class mask. This isolation is a hardship that some of my interviewees are even able to enjoy, but it is not the only hardship. On top of that lie discriminatory practices and humiliating judgments about their families and peers. The middle class mask is therefore a most ambivalent one: it makes it possible to resist discrimination alone by adopting a middle class “habitus”, but this implies the indignity of your working class self, and the impossibility to be recognized by others and unite in a common struggle against class discriminatory practices.

What a limitation is, after all

In my workshop I opened the reflexive space for discussions about class in design cultures. We did so by listening to the sound of sociological and historical “ruptures” I extracted from my interview transcripts. The examples were always related to very specific, visual and material objects of the Zurich design scene that I cannot display here. It was a great opportunity for me to explain the quality of inequality in Zurich to an international audience and to work with the participants through the oral surface of the quotes, trying to objectify the specificity of the empirical material.

How is it then that designers and social upward movers deconstruct the normativity of aesthetic categories today? I ask back – deriving the leitmotifs from the rich quotes provided by the interviewees, from their stream of unconscious and conscious social critique, from their attitude of rejection and approval of the design world – with the following questionnaire:

• At what point is the postulation for so called “good taste” opening a forum for debates, and when is it – on the contrary – “an aesthetic euphemism for social arrogance“?

• At what point is so called “talent” honored as an aesthetic potential for social revision, and when – on the contrary – is the ritualized regress to talent “an excuse for social reproduction through the similarity between the well-established and the newcomers“?

• At what point are so called “social media” really social in distributing cultural capital, and when – on the contrary – are social media “making a difference that gets bigger and bigger in a very attractive way“?

• At what point is so called “reductionism” a tool for democratic design, and when – on the contrary – “a modernist mannerism completely detached from its economical implication”?

• At what point is so called “inspiration drawn from the working class milieus” an economic acknowledgement of the creativity of the unskilled, and when – on the contrary – is it “a re-edition of slumming practices from Victorian age“?

• At what point is so called “sustainability” a value that works also for the poorest, and when – on the contrary – “an escapist and neurotic cocooning of the worried wealthy with no political grip“?

• At what point is so called “postmodernist irony” a true chance to evade paternalism in aesthetics, and when – on the contrary – “an aesthetically controlled joke at the cost of the underprivileged“?

• At what point does the so called “academization” of design schools help our students to reflect the diverse hierarchies within the design world, and when – on the contrary – is it an „intimidating curricular set of bourgeois attitudes“?

This provisional, incomplete questionnaire is here to consider what an invisible social limit is, after all: a very fine addition of very fine points that the struggle for a better life, at the end of the day, sums up to a great divergence. Further, and inspired by James Baldwin’s opening quotation, I would say that these points in my context are “choices one has got to make, for ever and ever and ever, every day“. Behind these choices lies the “terrible reality”, which is the true cost of what you believe to be real. No wonder Baldwin, in another essay uses quotes when asking: “Who can afford to ‘improvise’, at these prices?” (Baldwin 2010, 41 and 121). I echo this quote by asking who can afford to be “creative” at these prices – in Zurich and elsewhere?

As teachers, supervisors and mentors of the future generations of working class students in design, and as curators, critics, historians and sociologists of design, we should keep in mind the specific hardship of all upward movers into the field. The structure of my questionnaire, far more than its historically contingent content, therefore, is a concrete proposal of an epistemic tool for the gate-keepers and the door-openers of the field. We can use it to recalibrate our practices and judgements when it comes to class in design culture.

References

Opening Quotation

Baldwin, James. 2010. The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity, in: The Cross of Redemption. Uncollected Writings, New York/Toronto: Pantheon Books, p. 41.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Sara. 2004. Space Invaders. Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Space. Oxford/New York: Berg.

Baldwin, James. 2010. The Cross of Redemption. Uncollected Writings, New York/Toronto: Pantheon Books.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1987. Die Feinen Unterschiede. Kritik der gesellschaftlichen Urteilskraft, transl. by Berndt Schwibs and Achim Russer, Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 2010. Distinction. A social critique on the judgement of taste, transl. by Richard Nice, with a new introduction by Tony Bennett, London: Routledge Classics.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. The Rules of Art. Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, transl. by Susan Emanuel, Maldon: Polity Press.

Eribon, Didier. 2016. Rückkehr nach Reims, transl. by Tobias Haberkorn, Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Freud, Sigmund. 1999. Die Traumdeutung. Frankfurt. a. M.: Fischer Taschenbuch.

Marx-Engels Werke. 1957ff. Vol. 1–42, Berlin/DDR: Dietz.

Lazzarato, Maurizio. 1996. Immaterial Labour, in: Virno, Paolo, Michael Hardt, Radical Thought in Italy. A Potential Politics, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, pp. 133–147.

Saner, Philippe, Sophie Vögele, and Pauline Vessely. 2016. Schlussbericht Art.School.Differences. Researching Inequalities and Normativities in the Field of Higher Art Education. Zurich: Institute for Art Education, online: https://blog.zhdk.ch/artschooldifferences/schlussbericht/ (last access: 17.10.2017).

Seefranz, Catrin, and Philippe Saner. 2012. Making Differences: Schweizer Kunsthochschulen. Explorative Vorstudie. Zurich: Institute for Art Education, online: https://blog.zhdk.ch/artschooldifferences/files/2013/11/Making_Differences_Vorstudie_Endversion.pdf (last access: 17.10.2017).

Stamm, Margrit. 2016. Arbeiterkinder an die Hochschulen! Hintergründe ihrer Aufstiegsangst, Dossier 16/2. Fribourg: Swiss Education, online: margritstamm.ch/images/Arbeiterkinder%20an%20die%20Hochschulen!.pdf (last access: 17.10.2017).