Von Musik über Schauspiel bis hin zum Mediendesign – das künstlerische Feld ist von Vielfalt gekennzeichnet. Deutlich weniger vielfältig ist die soziale Zusammensetzung der Studierenden an den Kunstuniversitäten. Vielmehr genießen künstlerische Studien, und mit ihnen das künstlerische Feld insgesamt, den fragwürdigen Ruf, eine Angelegenheit für privilegierte „rich white kids“ zu sein. Inwiefern dieses Bild der Realität entspricht und was gegebenenfalls dagegen getan werden kann, besprechen Sophie Vögele und Philippe Saner im Interview mit Florian Walter für die KUPFzeitung. Die Kurzversion des Interviews findet sich auf der Website der KUPF. Unter Publikationen sind die vollständigen bibliographischen Angaben.

Florian Walter: Als „Auswahl der Auserwählten“ beschreiben Sie im Abschlussbericht zu ihrem Projekt Art.School.Differences die Aufnahmeverfahren an Kunsthochschulen. Wer schafft es an einer Kunstuni aufgenommen zu werden, wer nicht? Welche spezifische Rolle spielt Klasse(nzugehörigkeit) im Verhältnis zu anderen Faktoren wie etwa Geschlecht und Ethnizität?

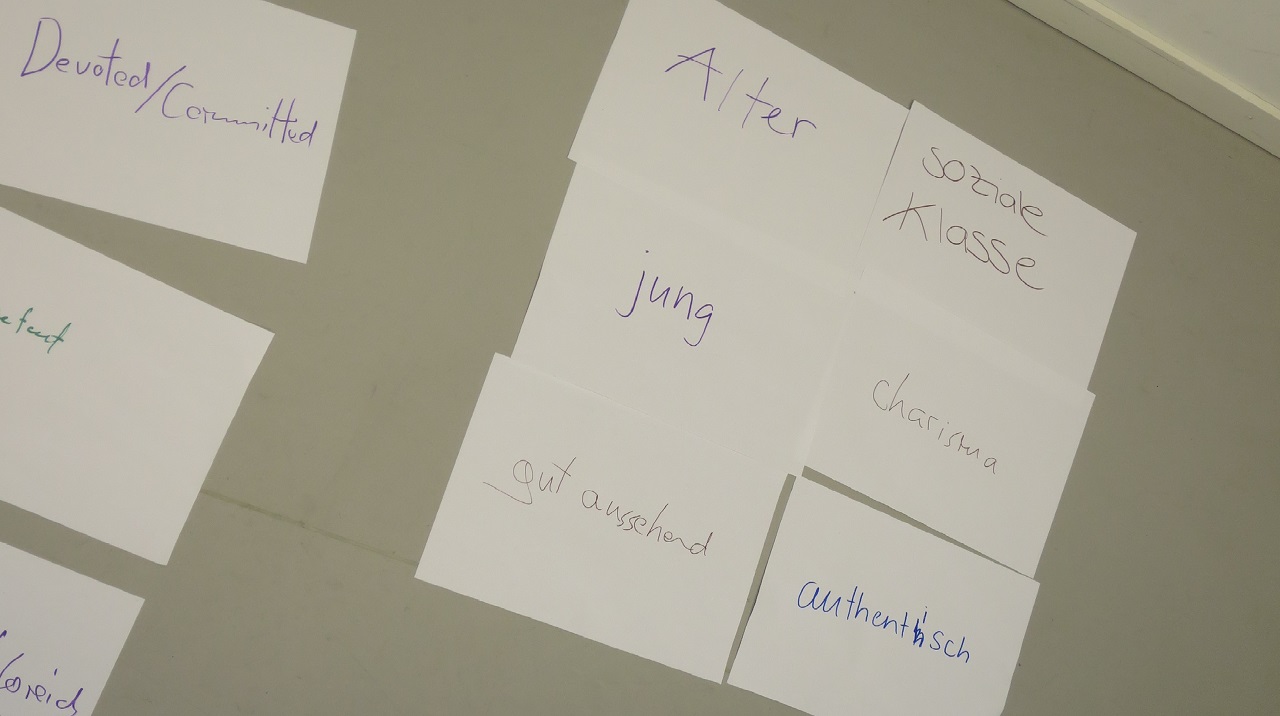

Sophie Vögele und Philippe Saner: Um zu verstehen, wer Zugang zum Kunsthochschulstudium hat ist es wichtig zuerst kurz auf die engen Verschränkungen zwischen den verschiedenen Identitätskategorien einzugehen und dabei vor allem hervorzuheben, dass es um Machtverhältnisse geht, die unterschiedlich wirken – wir orientieren uns hier am Konzept der Intersektionalität, wie es etwa von María do Mar Castro Varela und Nikita Dhawan verwendet wird.(1) Soziale Klassen, Geschlecht, Sexualität, race/Ethnizität und unsere Vorstellungen eines normativen Körpers sind historische Konstruktionen, die u.a. durch ein europäisches Verständnis einer aufgeklärten Moderne und in Abgrenzung zu den Kolonien etabliert wurden. Vorherrschende Bilder und Meinungen in unseren Köpfen bestätigen diese Verständnisse und definieren eine klar abgesetzte Norm. Unsere Studie zeigt deutlich auf, dass auch Schweizer Kunsthochschulen aus privilegierten Verhältnissen stammende, weisse, schweizerische, heterosexuelle Personen mit leistungsstarken, jungen und gesunden Körpern als Norm setzen. Alles was davon abweicht, wird als anders definiert. In der Verschränkung der Kategorien zeigt sich aber, dass gewisse Personen weder als anders klassifiziert werden noch die Möglichkeit haben, überhaupt in diesem Feld sichtbar zu sein. Bspw. ist der Zugang für ethnisch markierte und aus weniger privilegierten Verhältnissen stammende Leute nur sehr erschwert möglich. Personen, die als be/hindert oder körperlich beeinträchtigt erscheinen, müssen weiss sein und aus privilegierten Verhältnissen stammen, um als Andere aufzutauchen. Wenn also Personen mit weniger privilegiertem Hintergrund überhaupt aufgenommen werden, sind diese immer weiss, jung mit einem gesund anmutenden Körper. In diesem Sinne ist auch die „Auswahl der Auserwählten“ zu verstehen: Die Gruppe, die überhaupt in Frage kommt Zugang zur Kunsthochschule – und damit auch eine Sichtbarkeit – zu erhalten, setzt sich bereits aus „Auserwählten“ zusammen. Die Ausgrenzung aufgrund der Klassenzugehörigkeit kann deshalb nicht im Verhältnis zu anderen Diskriminierungskategorien verstanden werden, sondern ist nur in der Verschränkung mit diesen aufschlussreich. Diese Normierung der Studierenden – aber auch der Dozierenden und weiteren Mitarbeitenden der Kunsthochschulen – unterscheidet sich nicht wesentlich unter den Studiengängen.

Gibt es Unterschiede zu anderen Hochschulen?

In unserer Studie haben wir drei Schweizer Kunsthochschulen untersucht, die eine etwas andere Tradition als die österreichischen Kunstuniversitäten bzw. Akademien aufweisen. Die Tradition der Kunstgewerbeschule, die bis heute ein wichtiger Bezugspunkt für die Identität der heutigen Kunsthochschulen darstellt, hat sich lange durch die Zugänglichkeit für Kinder aus Arbeiter*innen- und Handwerker*innenfamilien ausgezeichnet – wobei allerdings Frauen bis weit in die zweite Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts marginalisiert blieben. Heute gehören die Kunsthochschulen im Schweizerischen Bildungssystem zu den Fachhochschulen, von denen sie sich in verschiedenen Punkten deutlich unterscheiden. Bezüglich der sozioökonomischen Herkunftsmilieus (gemessen an Berufen und Bildungsabschlüssen der Eltern der Studierenden) sind sie den Universitäten, und hier v.a. traditionellen Elite-Ausbildungen wie Medizin oder Jurisprudenz, deutlich näher. Ein wichtiger Grund für diese exklusive Zusammensetzung sind die strengen Aufnahmeverfahren, die im Schweizer Bildungssystem nur in der Medizin vorzufinden sind. Um diese bestehen zu können, bedarf es der jahrelangen künstlerischen Praxis und Vorbereitung, was wiederum nicht allen sozialen Klassen gleichermaßen zugänglich ist. Hinzu kommt, dass das Studium sehr anspruchsvoll, zeitintensiv und körperlich streng ist. Gerade in den darstellenden Disziplinen wie Schauspiel und Musik, teilweise aber auch in den anderen, ist bereits das Studium auf permanenten Wettbewerb ausgerichtet. Es stellt sich also nicht nur die Frage, wer kommt rein, sondern auch: wer verfügt über die notwendigen Ressourcen, um drin zu bleiben.

Um im Kulturbereich erfolgreich zu sein, braucht man ein finanzstarkes Elternhaus (und eine Eigentumswohnung), muss man sich in abgehobenen Kunstdiskursen mitteilen können und auf ein Netzwerk im Kunstbetrieb bauen können. Soweit die Annahme. Stimmt das? Und was hat das alles mit „Klasse“ zu tun?

Wie schon erwähnt sind für eine erfolgreiche Aufnahme und dann auch noch ein erfolgreiches Studium alle genannten Ressourcen notwendig. Wenn davon etwas nicht aufgebracht werden kann, muss es kompensiert werden durch noch bessere Leistungen etc. Beispielsweise gibt es die Möglichkeit für Aufnahmen sur dossier, etwa wenn der erforderliche Bildungsabschluss (in der Regel eine Maturität) fehlt. In der Terminologie der Kapitalien nach Bourdieu entspricht die Norm an Kunsthochschulen einer privilegierten Herkunft: Sie stammen überwiegend aus den Klassen der soziokulturellen Professionellen bzw. Semi-Professionellen(2) wie Künstler*innen, Lehrpersonen, Akademiker*innen etc. – also denjenigen Berufen, zu denen sie als Absolvent*innen von Kunsthochschulen teilweise selbst zählen werden. Hier bildet sich also ein auch gesamtgesellschaftlich betrachtet überaus hohes Mass an sozialer Reproduktion ab. Unsere Ergebnisse zeigen, dass insbesondere kulturelles und soziales Kapital, das nicht bereits von zu Hause mitgebracht wird, anderweitig kompensiert werden muss. Dies führt sinngemäß zu zusätzlichen Belastungen, die neben einem intensiven Studium, Erwerbsarbeit und z.T. auch Betreuungsverpflichtungen für nicht-weisse, aus nicht privilegierten Verhältnissen stammende Personen sehr schwierig zu stemmen sind. Zusätzlich problematisch hierbei ist, dass sich diese Prozesse des Ausschlusses aus dem Kunsthochschulfeld nur punktuell zeigen und sonst verdeckt bleiben: Ausgeschlossene suchen Erklärungen in ihren persönlichen Präferenzen und Leistungen, das Scheitern wird als individuelles Versagen betrachtet. Eine Auswahl wird von allen Akteur*innen (Kandidat*innen wie Dozierenden) als notwendig erachtet – gerade auch von denjenigen, die aufgrund nicht-normativer Hintergründe oder Erfahrungen mit institutionellen Diskriminierungen rechnen müssen. Die beschriebene vorherrschende Norm an Schweizerischen Kunsthochschulen (unter 1a) definiert nicht nur die Auserwählten, sondern verbirgt auch die Prozesse von Ein- und Ausschluss, die zur Entstehung dieser Gruppe notwendig sind: Es kann von einer Camouflage von Diskriminierung durch Normierung gesprochen werden.

Ist die Ungleichheit an Kunstuniversitäten nur eine Fortsetzung der Auswahl in den Kindergärten und Schulen? Oder wählen Unis anders aus als Kindergärten, Volks- und Mittelschulen?

Selbstverständlich finden Praktiken von Ein- und Ausschluss schon vorher in den unterschiedlichen Vorbildungen statt. Und die Kunsthochschulen können aus den bereits vorausgewählten Kandidat*innen auswählen – „es kommt bereits alles gemacht“, wie es ein Dozierender in einem Interview formulierte. Diverse Reformen in der Hochschulpolitik (Einführung des Fachhochschulstatus, die Bologna-Reformen und die Fusion verschiedener Hochschulen) in den 1990er und 2000er Jahren haben dazu geführt, dass sich die frühere Heterogenität der Zugangswege markant reduzierte, während gleichzeitig die gymnasiale Maturität mit Anteilen zwischen 50–70% zum eigentlichen Standard wurde. Die soziale Exklusivität des Feldes erhöht sich also auch über die unterschiedlichen schulischen Zugangswege und bildet somit die elterlichen Bildungshintergründe bzw. Berufsklassen ab. Allerdings hat unsere Studie auch gezeigt, dass die Aufnahmeverfahren selbst nicht immer linear funktionieren: Kandidat*innen können vorgezogen werden und einzelne Ausbildungsphasen überspringen, wenn ihr „Talent“ als besonders groß erachtet wird. Andere wiederum werden in ‚Warteschlaufen‘ (weitere Vorbereitungskurse) geschickt, mit der Bitte, es doch im nächsten Jahr nochmal zu versuchen. Die verschiedenen Vorläuferinstitutionen (künstlerische Gymnasien, Vorkurse und Vorstudium etc.) sind oft miteinander verknüpft, es bestehen auch personelle Austauschbeziehungen, ‚man kennt sich‘. In dieses Feld überhaupt reinzukommen und sich darin behaupten zu können, ist insofern sicherlich eine wichtige Voraussetzung. Neben der ‚offiziellen‘ Auswahl im Prozess der Aufnahmeverfahren sind des weiteren spezifische Informations- und Adressierungspolitiken zu nennen, bspw. in gedruckten Materialien oder Webauftritten: Hier hat unsere Studie auch gezeigt, dass die Kunsthochschulen nicht einfach alle potentiellen Kandidierenden ansprechen, sondern durch Bilder und Texte ganz bestimmte Gruppen adressieren, während viele gar nicht erst auftauchen. Hier sind insbesondere Kandidat*innen aus migrantischen Arbeiter*innenmilieus zu nennen, denen die Fähigkeit abgesprochen wird, sich überhaupt im Umfeld einer Kunsthochschule bewegen zu können.

Die Einkommensverteilung entwickelt sich zunehmend auseinander. Die Reichen werden reicher, die Armen ärmer. Welche Folgen hat das auf den Kunstbetrieb? Werden sich bald nur mehr Rich Kids leisten können, Kunst und Kultur zu machen?

Wir haben die zunehmende Ungleichheit in der Einkommens- und Vermögensverteilung nicht spezifisch untersucht. Was die Kunsthochschulen allerdings gegenüber anderen Schulen und Hochschulen auszeichnet, sind die Internationalisierungsbestrebungen, was an die vorherige Antwort anschließt: Unsere Studie hat gezeigt, dass vermehrte Rekrutierung von sogenannten ‚internationalen Studierenden‘ ganz deutlich zu einer Verstärkung der existierenden sozialen und kulturellen Ungleichheiten beiträgt. Studierende mit transnationalen Biografien, die sich in verschiedenen Sprachen eloquent im Kunstfeld bewegen können, sind natürlich gerne gesehen. Zum notwendigen kulturellen und sozialen Kapital kommt spezifisch bei diesen Studierenden viel ökonomisches Kapital sowie die ‚richtige‘ Staatsangehörigkeit hinzu, die solche Arbeits- und Lebensweisen überhaupt ermöglichen. Wie ja auch die Studie von Barbara Rothmüller zur Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien gezeigt hat, sind ökonomisch gut situierte Studierenden aus EU-Mitgliedsstaaten deutlich übervertreten.(3) Insofern wird die zunehmende Internationalisierung bestimmt Folgen für den Kunstbetrieb haben; welche, darüber können wir allerdings bloß spekulieren.

Wie haben sich Zugangsbarrieren an Kunstunis in den vergangenen Jahren/Jahrzehnten entwickelt? In welchen Bereichen gibt es einen Anstieg der Zugangsungleichheit?

Wir konnten die Zugangsbarrieren nicht in einer historisch-vergleichenden Perspektive untersuchen. Was sich allerdings aus den Ergebnissen zur sozialen Zusammensetzung der Studierenden bezüglich elterlichen Berufsgruppen und Bildungsmilieus sowie den genannten Internationalisierungsbestrebungen andeutet, ist eine deutliche Zunahme von Studierenden aus sozioökonomisch privilegierten Milieus mit hohem kulturellen Kapital – dies betrifft insbesondere die stark internationalisierten Bereiche der Kunsthochschulen, wie die klassische Musik und die bildende Kunst. Schauspiel mit seinem Fokus auf die deutsche Sprache, Design und künstlerische Vermittlung (Lehramt) in geringerem Ausmaß, weil diese noch stärker auf die hiesigen Kunst- bzw. Arbeitsmärkte ausgerichtet sind.

Was spricht dagegen, dass nur mehr Rich Kids Kunst studieren? Wie bringen wir mehr Kinder aus Arbeiter/innenfamilien an die Kunstunis? Warum überhaupt sollten Arbeiterkinder an die Kunstuni wollen, wenn danach ein prekäres Künstler/innenleben auf sie wartet?

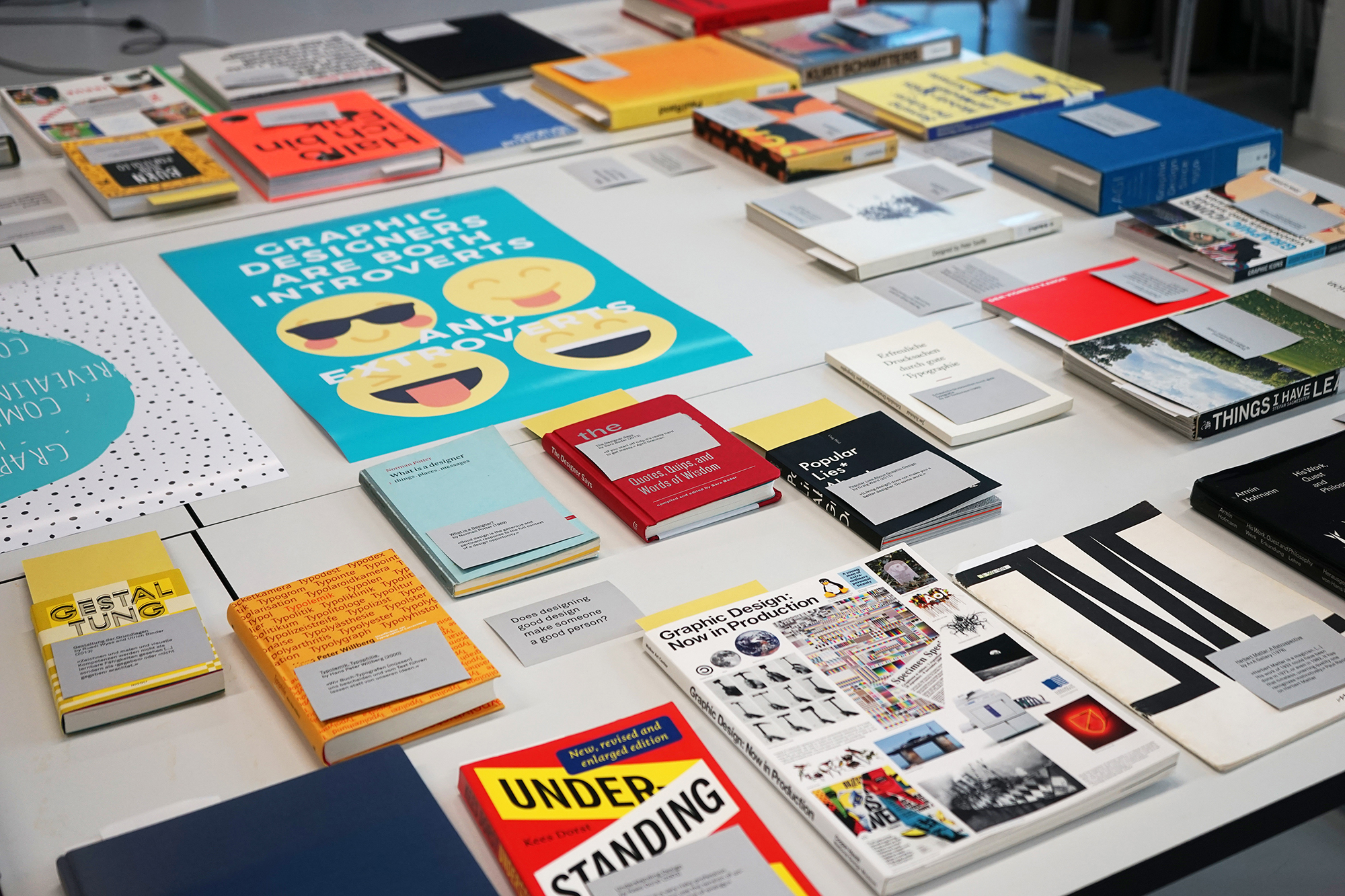

Zunächst einmal scheint es uns wichtig darauf hinzuweisen, dass Kunsthochschulen – wie auch andere Institutionen des Kunstfeldes wie Museen, Theater oder Opernhäuser – als öffentlich finanzierte Bildungsinstitutionen für alle zugänglich sein sollten. Gerade im Wissen um die sozialen ungleichen Zugangsbedingungen – die Erkenntnis ist ja keineswegs neu, wenn man an die Arbeiten Bourdieus in den 1960er Jahren denkt – sollten diese kontinuierlich an der Öffnung und Demokratisierung der Zugangswege und auch ihrer eigenen Strukturen arbeiten. Das geschieht im Kunstfeld in regelmäßigen Abständen schon, nur allzu oft verpuffen die Bemühungen nach einer gewissen Zeit. Außerdem handelt es sich um ein Feld, das obwohl prekarisiert, weiterhin ein hohes Ansehen genießt und mit Versprechungen von Offenheit, Innovation und Kreativität operiert. Wie etwa die Arbeiten zum „neuen Geist des Kapitalismus“(4) gezeigt haben, wurden diese Begriffe und Konzepte längst auf andere Bereiche übertragen und haben insofern gesellschaftliche Wirkungsmacht erlangt. Auch scheint uns wichtig einzubringen, dass Kunst eine Vielfalt an wirkmächtiger „Sprache“ bemüht, die kritisch und politisch sein kann. Es scheint uns deshalb grundlegend, dass nicht nur eine kleine Gruppe von „Auserwählten“ auf Bühnen auftritt oder Filmszenarien schreibt, sondern stattdessen die gesellschaftliche Diversität der Kultur- und Kunstschaffenden, die es jenseits der Kunsthochschulen ja durchaus gibt, in den genannten Institutionen auch repräsentiert wird.

Wie können die Zugangsbarrieren verringert werden? Werden Maßnahmen – etwa seitens der Kunsthochschulen oder der Politik – umgesetzt oder sind sie möglicherweise gar nicht erwünscht? Will man lieber unter sich bleiben?

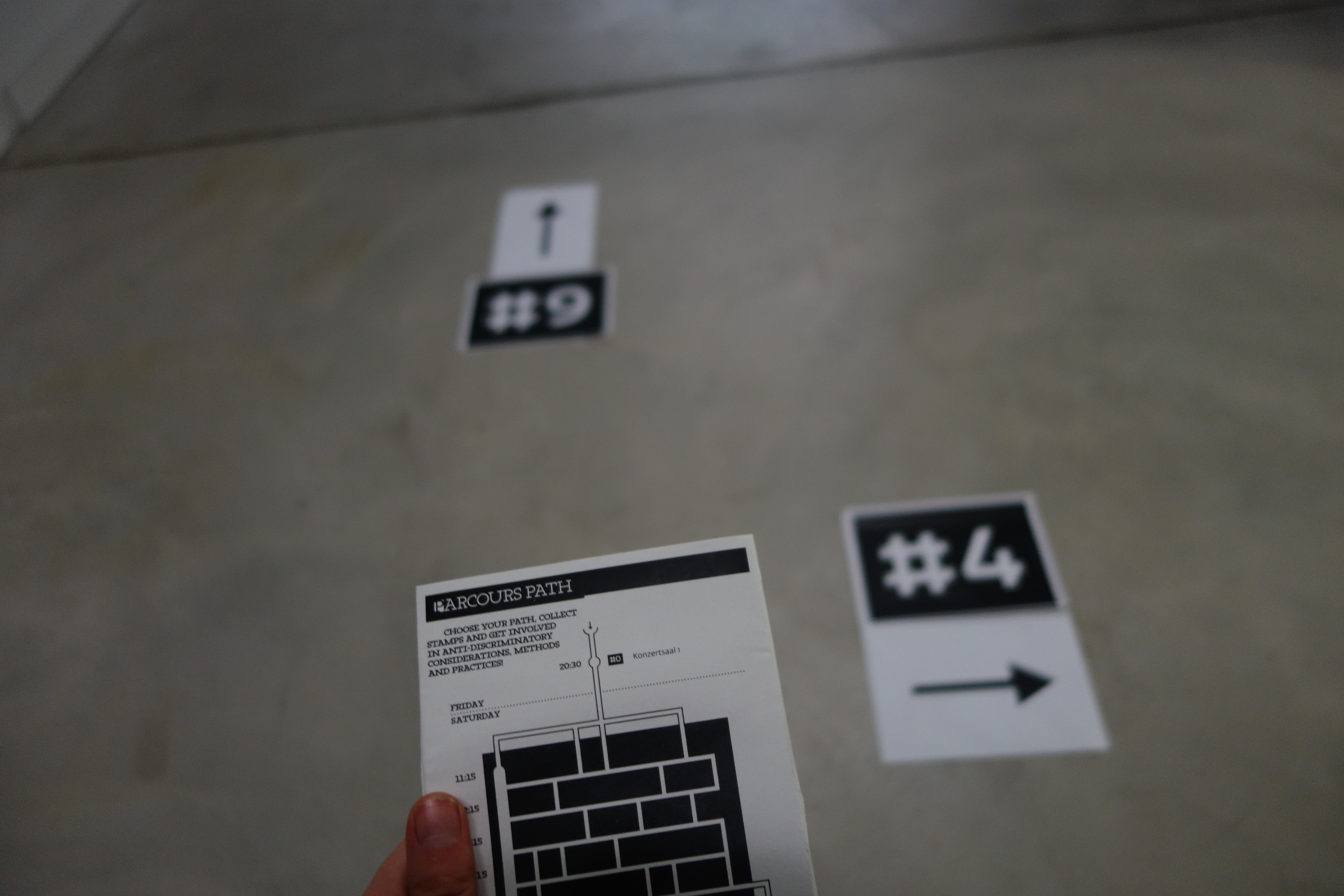

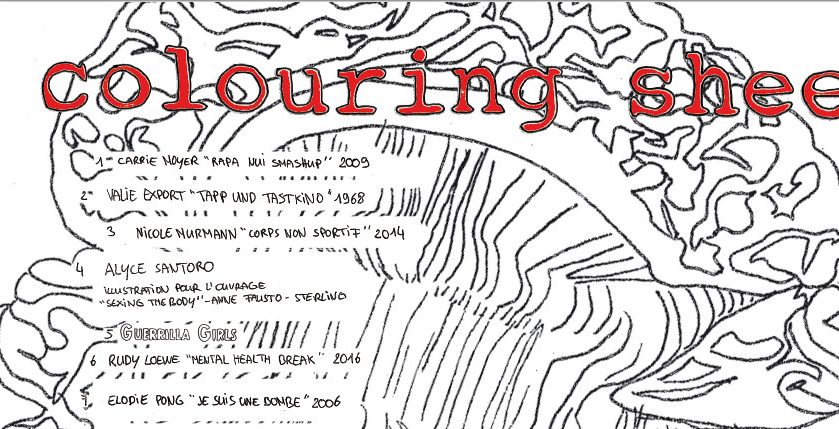

Wir haben in unserem Abschlussbericht auf sechs verschiedene Handlungsfelder hingewiesen, die von den Aufnahmeverfahren und deren Ausgestaltung (bspw. Informationspolitiken, finanzielle Anforderungen, Auswahlkriterien) über die Curricula und die Bedingungen während des Studiums bis hin zu den Organisationsstrukturen und Politiken der Hochschulen reichen. Neben der Adressierung konkreter Mechanismen des Ein- und Ausschlusses von Kandidat*innen ging es auch um organisatorische, letztlich gesellschaftliche Fragen demokratischer und inklusiver Prozesse innerhalb der Kunsthochschulen und darüber hinaus. Leider hat sich allerdings sehr großer institutioneller Widerstand gezeigt, den wir nicht nachvollziehen können: eine zeitgemäße, kritische Auseinandersetzung mit den Erkenntnissen der Studie und mit Diversität (5), d.h. mit gesellschaftlichen Vorstellungen und der intersektionalen Verschränkung von Klasse, Geschlecht, Sexualität, race/Ethnizität und Körper und ihren Auswirkungen in Aufnahmeverfahren, Studium und Curricula sollte zum Kerninhalt der institutionellen Hochschul- und Qualitätsentwicklung werden. Dies würde langfristig den Bestrebungen nach mehr internationaler Visibilität und gleichbleibenden oder sogar steigenden Bewerber*innenzahlen entsprechen wie eine niederschwellige Weiterführung der Auseinandersetzung in einem Studiengang Bachelor Art Education gezeigt hat. Die Hochschulen unterstützen bisher diese Initiativen nicht obwohl das im Wortlaut ziemlich exakt auf die Formulierung ihrer strategischen Ziele passt und haben sich – wenn überhaupt – lediglich mit den ‚technischen Fragen‘ wie der Formulierung von Aufnahmekriterien beschäftigt. Es scheint uns, dass die Verweigerung der Auseinandersetzung mit diesen Inhalten auf die Sicherung eigener Privilegien und der Wahrung bestehender Machtverhältnisse innerhalb der Hochschulen zurück zu führen sind.

Wie wirkt sich die Ungleichheit an den künstlerischen Hochschulen auf den Kunstbetrieb im Allgemeinen aus? Welche Handlungsaufträge ergeben sich für Kulturhäuser, Theater, Museen, etc.?

Bisher haben wir uns nicht konkret mit anderen Institutionen des Kunstfeldes befasst. Trotzdem scheinen uns die identifizierten Handlungsfelder aufgrund unserer Studie auch für Museen, Theater oder Opernhäuser relevant zu sein: Wir erachten eine kritische Auseinandersetzung mit Machtverhältnissen, die das Kunstfeld und Gesellschaft überhaupt regieren, als notwendig. Die Auseinandersetzung mit diesen Fragen sollte weder an künstlerische Produktionen, die dies in unterschiedlicher Form ja durchaus verhandeln, noch an die institutionell schwach positionierten Gleichstellung- bzw. Diversity-Fachstellen ‚ausgelagert‘ werden. Die eigenen Prozesse und Verfahren diesbezüglich kontinuierlich zu befragen mit dem Ziel deren Veränderung sollte zu einem der Kernanliegen der jeweiligen Organisationen und ihrer weiteren Entwicklung werden.

Florian Walter ist Politologe und Kulturarbeiter, u.a. beim Kulturverein `waschaecht‘ (Wels, Österreich) und Vorstand der Kulturplattform Oberösterreich

(1) Castro Varela, María do Mar/Dhawan, Nikita (2011): Soziale (Un)Gerechtigkeit. Kritische Perspektiven auf Diversity, Intersektionalität und Antidiskriminierung. Berlin: LIT.

(2) Die Bezeichnung entnehmen wir Oesch, Daniel (2006): Redrawing the Class Map. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

(3) Rothmüller, Barbara (2010): BewerberInnen-Befragung am Institut für Bildende Kunst 2009. Wien: Akademie der bildenden Künste. Online unter: https://www.akbild.ac.at/Portal/organisation/uber-uns/Organisation/arbeitskreis-fur-gleichbehandlungsfragen/endbericht.pdf?set_language=de&cl=de (letzter Zugriff: 31.05.2018).

(4) Boltanski, Luc/Chiapello, Eve (2003): Der neue Geist des Kapitalismus. Konstanz: UVK.

(5) Steyn, Melissa (2015): Critical diversity literacy. In Vertovec, Steven (Hrsg.), Routledge International Handbook of Diversity Studies. New York & Abingdon: Routledge, 379-389.