Cet article est à disposition qu’en Allemand.

(Deutsch) Aneignungen unserer Institutionen

Désolé, cet article est seulement disponible en Deutsch.

(Deutsch) Demokratisierung der Kunstuniversität: Ein Gespräch an der UdK

(Deutsch) “Let’s talk about race” und “tête noire”

Désolé, cet article est seulement disponible en Deutsch. Continue reading (Deutsch) “Let’s talk about race” und “tête noire”

Lettres ouvertes Black artists in Switzerland et par les étudiants de l’ECAL: Des mesures antiracistes demandées dans des lieux culturels en Suisse

Black Artists and Cultural Workers in Switzerland: Lettre ouverte. https://blackartistsinswitzerland.noblogs.org/

La Matinale / 1 min. / le 3 juillet 2020: https://www.rts.ch/info/culture/11445917-des-mesures-antiracistes-demandees-dans-des-lieux-culturels-en-suisse.html

L’affaire George Floyd a des répercussions dans le monde culturel suisse. Il y a deux semaines, un collectif d’artistes noirs de Suisse a envoyé une lettre à une cinquantaine de lieux culturels pour réclamer des mesures antiracistes. Une démarche similaire est lancée à l’ECAL à Lausanne. Des étudiants de l’Ecole cantonale d’art de Lausanne (ECAL) ont envoyé une lettre ouverte à leur direction et leurs enseignants pour demander des mesures contre les discriminations raciales. Ce collectif, auquel la RTS a pu parler, tient à rester anonyme. Il a publié sa lettre ouverte sur le réseau Instagram et demande à l’ECAL différentes mesures structurelles, comme la transparence sur les sponsors – certains génèrent-ils des fonds provenant d’exploitation coloniale? Mais aussi des mesures incitatives, comme l’invitation d’artistes noirs ou la création de formations obligatoires contre le racisme.

Plus facile d’être homme et blanc

Chercheuse à l’Ecole d’art de Zurich, Sophie Vögele a participé à une étude qui montre qu’en Suisse, les admissions dans les écoles d’art, ainsi que tout le cursus, sont discriminants. Elle soutient la démarche des étudiants de l’ECAL. “Plein de statistiques et de recherches montrent qu’il est beaucoup plus facile d’être un artiste masculin et un artiste blanc dans le monde”, a-t-elle souligné vendredi dans La Matinale. Les écoles font partie de ce champ-là, poursuit-elle. “Dans la lettre, on parle de ‘démanteler les structures du pouvoir blanc’. C’est cela qu’il faut adresser. Comprendre ce qui règne sur notre pensée, ou comment les structures sont imprégnées par une certaine manière de penser, qui est justement très blanche”.

Lettre ouverte des étudiants de l’ECAL [Voir aussi sous le compte Instagram des initiant*es.]“Cher Alexis Georgacopoulos, chers enseignant.e.s, chères personnes au pouvoir, Cette lettre ouverte vise à répondre à notre premier appel en faveur de mesures immédiates que nous pensons que l’ECAL, ainsi que d’autres établissements d’enseignement, ont la responsabilité de mettre en œuvre. La réponse que nous avons reçue du directeur de l’ECAL soutient que notre établissement ne compte prendre aucune mesure particulière pour ouvrir la voie à un changement progressif et durable au sein de l’institution. Étant donné que la réponse de l’ECAL ne répond à aucune des préoccupations que nous avons décrites en détail dans notre première lettre, nous vous demandons une fois de plus de prendre en considération les mesures à long terme proposées contre les discriminations raciales, et en faveur de plus de transparence et d’inclusion. En tant qu’établissement d’enseignement supérieur qui n’a pas de politique, de programme ou de système mis en place afin de lutter contre la racialisation, la symbolisation* et la discrimination des étudiant.e.s, il est extrêmement contestable pour l’ECAL d’affirmer être un établissement précurseur de l’industrie de l’art et du design. Dès lors, revendiquer une notion d’unité et d’ouverture est insuffisant, spécialement en considérant que cette responsabilité nous est remise à nous, étudiant.e.s blanc.h.e s et étudiant.e.s de couleur. En grande majorité, nous sommes déçu.e.s par le manque d’action et de soutien visant à démanteler les structures de pouvoir blanc au sein de l’ECAL, et c’est pourquoi nous vous invitons à mettre en pratique la liste des demandes structurelles** que nous avons décrite dans notre première lettre. Bien que nous prenions en compte la considération que notre lettre a suscitée, nous estimons toujours que la position neutre de l’ECAL est totalement inacceptable dans cette situation. En ce sens, nous ne pensons pas que garder le silence soit une posture légitime, ni en tant qu’entité publique, ni dans un espace interne et structurel. Nous comprenons qu’il s’agit d’un moment critique de questionnement pour les personnes non-touchées par le racisme, et nous invitons la direction de l’ECAL à se joindre au corps étudiant, principalement blanc, afin d’ensemble réfléchir à des questions que nous n’avons pas examinées auparavant. Nous voulons également souligner l’importance d’avoir un dialogue ouvert entre la direction de l’ECAL et ses élèves, afin que nous puissions travailler ensemble vers une école qui reflète nos valeurs. Dans sa réponse, le directeur de l’ECAL a appuyé ses propos sur une citation de Nelson Mandela qui dit que “l’éducation est l’arme la plus puissante que vous pouvez utiliser pour changer le monde”. Nous sommes en accord avec ces mots, et c’est précisément l’une des raisons pour lesquelles beaucoup d’entre nous ont décidé de poursuivre des études supérieures. Cependant, l’ECAL, qui se prévaut d’un enseignement critique, encourage pourtant le corps étudiant à développer cette même éducation selon leur libre arbitre et intérêts personnels. Un établissement qui se positionne comme progressif ne peut pas laisser la responsabilité d’une éducation critique au bon-vouloir de ses étudiant.e.s. Notre système éducatif ne devrait pas se sentir en droit de s’approprier les travaux critiques des élèves à son profit, et ainsi se décharger de la culpabilité de son échec à résoudre les problèmes critiques de race, de classe et de sexe depuis l’intérieur. Nous insisterons à ce sujet jusqu’à ce que des mesures concrètes soient prises. Nous attendons de l’ECAL qu’elle se joigne au mouvement mondial contre le racisme, et agisse contre la complicité institutionnelle d’un système bénéficiant aux personnes blanches. Prenons par exemple le manque de transparence concernant les sponsors et les partisans de l’ECAL: quelles politiques existantes sont mises en place pour garantir que les fonds ne proviennent pas de sources qui profitent directement ou indirectement de l’exploitation des populations noires? Nous attendons un changement radical dans la transparence, et le réexamen des pouvoirs en place. Ce manque d’implication provoque également certains conflits en termes d’attentes académiques: comment l’ECAL peut-elle s’attendre à ce que le travail des élèves soit critique, lorsque l’école n’est pas disposée à dispenser une telle éducation? Comment peut-elle revendiquer le mérite d’un travail étudiant critique, tout en refusant de mettre en place des structures internes activement antiracistes? De quelle manière l’ECAL préconise-t-elle et donne-t-elle de la visibilité aux projets qui remettent en question les structures de pouvoir existantes définies par la race, la classe et le genre? Pour conclure, nous tenons à souligner qu’il est crucial pour l’ECAL (ainsi que d’autres établissements d’enseignement) d’utiliser son pouvoir et son impact dans le monde de l’art en s’exprimant en faveur des préoccupations susmentionnées. Nous attendons de notre université qu’elle offre à ses étudiant.e.s la perspective d’un avenir conforme à nos valeurs : celles qui accordent à tous.tes la possibilité d’évoluer en toute sécurité et dignité, et de prospérer en égalité dans leurs carrières. Le corps étudiant de l’ECAL** Nous vous invitons à mettre promptement en vigueur la liste suivante non exhaustive de demandes structurelles : Transparence sur les sponsors – Qui sont les sponsors / donateurs de l’ECAL, et génèrent-ils de quelque manière que ce soit des fonds provenant d’exploitation coloniale ? – Quelle éthique l’ECAL applique-t-elle lorsqu’il s’agit du choix des sponsors desquels accepter des financements ? – Y’a-t-il des fonds mobilisés pour des causes inclusives, que ce soit sous forme de dons à des organisations ou en interne sous forme de bourses ? Transparence sur toute éventuelle différence salariale – Y a-t-il des différences salariales en fonction de la couleur de peau ou du genre ? Si oui, pouvez-vous y remédier ? Transparence concernant l’emploi de personnel noir, tout en leur fournissant un environnement de travail sûr – Les cachets pour le travail d’artistes noir.e.s sont-ils les mêmes que pour le travail d’artistes blanc.he.s ? – Quelles mesures l’ECAL prend-elle pour offrir un environnement de travail sûr aux personnes noires et de couleur ? – Y’a-t-il un système en place qui assure un moyen digne de signaler les cas de racialisation, de discrimination et de symbolisation** ? – L’ECAL prend-elle des mesures spécifiques afin de fournir un environnement de travail sécurisé aux artistes racisé.e.s qui sont invité.e.s à donner des workshops /conférences ? Si oui, de quelle manière ? – Quelles sont les mesures prises par l’ECAL pour offrir un environnement de travail sûr aux personnes noires et aux personnes de couleur ? – Les enseignant.e.s sont-ielles invité.e.s et encouragé.e.s à s’informer activement sur un ensemble d’artistes, de curateur.trice.s et de galeries plus inclusives ? Invitez activement les enseignant.e.s à se renseigner sur les artistes, les curateur.tric.x.e.s et les galeries noires – Les artistes noir.x.e.s sont-ils pris en compte au même degré sans avoir à forcément devoir travailler sur des questions raciales ? – Dans quelles mesures les opinions coloniales sont-elles sérieusement remises en question en ce qui concerne l’art et la culture qui sont discutés au sein de l’institution ? – Comment l’ECAL garantit-elle une formation critique à ses employé.e.s ? Invitez des artistes racisé.e.s à organiser des conférences et des ateliers, tout en veillant à leur fournir un environnement de travail sûr Workshops obligatoires contre le racisme – Supposer et éloger l’union ne suffit pas. Que faites-vous pour démanteler la suprématie blanche dans votre établissement ? – Votre personnel est-il informé des préjugés suprémacistes blancs qui sont ancrés dans la société, la culture et la politique suisse et occidentale ?” – Accueillez-vous les plaintes des étudiant.e.s et les rapports sur les mauvais comportements des autres étudiants, des membres du personnel et des enseignants, et faites-vous en sorte que les étudiants qui les signalent se sentent en sécurité ? – Pouvez-vous régulièrement effectuer des sondages périodiques (démonstratifs des notions d’égalité et de diversité) qui recueillent les opinions et la satisfaction des étudiant.e.s concernant le corps des enseignants, des intervenant.e.s et le contenu de cours ? L’éducation extracurriculaire – Puisque l’ECAL encourage les étudiant.e.s à poursuivre une éducation critique en dehors du programme d’études, quelles mesures ont été prises par l’établissement pour fournir l’infrastructure, les outils et les ressources nécessaires? Ce point est particulièrement important puisque dans le dernier mail (10/06/20), l’ECAL y encouragerait les étudiant.e.s à développer un point de vue critique en dehors du cadre éducatif de l’école. * Symbolisation Le terme symbolisation a été utilisé en l’absence d’un terme français équivalent au terme anglais tokenisation, c’est-à-dire l’acte de faire un geste vers l’inclusion des membres de groupes minoritaires, destiné à créer une apparence d’inclusivité pour s’écarter des allégations de discrimination.

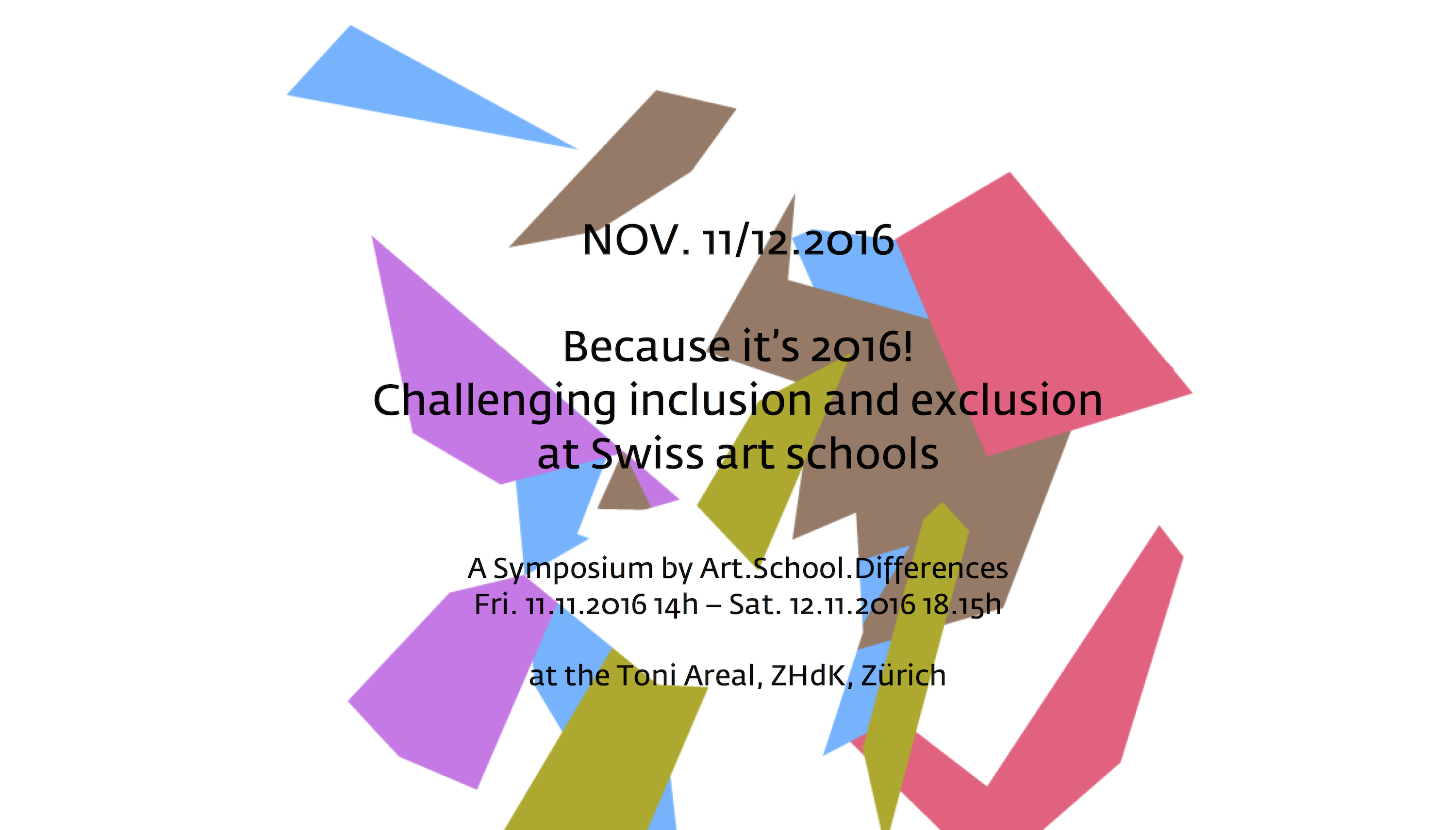

PARSE conference 2017 EXCLUSION

The 2017 biennal PARSE conference on EXCLUSION tackled very current questions of inequality, neocoloniality and legitimacy as they are expressed and produced through culture and cultures of artistic education.

November 15–17, 2017. Venue: Faculty of Fine, Applied and Performing Arts, Gothenburg, Sweden.

copyright of photo: Minjeong Ko, Globala Tanter at PARSE Gothenburg, 2017

The conference was structured in 6 strands:

Indigeneity is for many a politically enabling construct in resisting ongoing colonialisms, expropriations, and associated epistemic violence. It is also marked by multiple exclusions: conceptually, as irredeemably rooted in essentialism, primordialism and primitivism; strategically, as counter-productively factionalising and exoticising; juridically and pragmatically, as untenable within the various regimes of globalisation.

Educational exclusion addresses mono-cultural aspects of arts education as well as proposes how education in the arts can be fundamentally reshaped to become more accountable to manifold embodied knowledge practices.

Colonisation and Decolonisation addresses colonial and master paradigms in the arts as well as institutional, communal and collective perspectives and looks to strategies for a new arts and humanities that embraces epistemic and disciplinary disobedience, non-capitalist, pluri-national institutions and modes of aesthetic production.

Geographies of Exclusion addresses how social, cultural, political and economic barriers produce and sustain public spaces, public spheres, public memory, borders and migrants and their experiences of movement through the logic of circulation managed, controlled, and regulated by state authorities, public institutions, NGOs and private firms. It also addresses how such dominating modes of productions can be transgressed through civil counter-actions and independent self-organised practices.

Vocabularies of Exclusion focuses on forms of exclusion produced through language as well as embodied and discursive practices. Reflecting on the terms and conditions of artistic and political work in cross-disciplinary contexts, it explores and interrogates languages of inclusion, separation, and participation as they are produced and enacted in the present moment in the field of cultural production and its context in wider socio-political arenas.

Participation as Exclusion deals with the fact that “participatory turn” in cultural production, urban development, and so forth is now a dominant theme in Western art and design discourses and practices as well municipal governance, where it has moved from a marginalised area of community practice into the mainstream. This consideration inquires who the subjects of participation are and how and from where they were selected. It addresses questions such as Why are certain people seen to be in greater need of receiving participatory “support”? How, if at all, is power and decision-making redistributed?

Art.School.Differences was present in the Educational Exclusion strand with a presentation about: Exclusion from inside out: The intersectional working of class in artistic education. Refer to the web for the abstract. See the powerpoint presentation Exclusion inside out for download.

To watch the conference keynotes online, please refer to PARSE conference Afterwards. Meanwhile the Parse Journal “Exclusion”, Issue 8 Autumn 2018 with conference contributions has been published.

For an action plan to curb ongoing exlusion of minority groups, refer to the list proposed by Craig Wilkins during his talk that he made available for our blog.

Refer also to the Manifesto launched at PARSE Exclusion Conference November 2017. The Manifesto is the result of a two-day Learning Lab inspired by the self-organising work of the Restad Gård Support Group Network at Akademin Valand, Göteborgs Universitetet (see also Kultur i Väst). The Manifesto author’s shared aim is to highlight the current realities of social and cultural segregation effecting asylum-seekers and refugee communities living in Gothenburg and to make improvements to this situation. The Manifesto has been collectively drafted by members of the Restad Gård Self-Support Group Network, representatives from Valand Academy, Outgrain, Counterpoints Arts and individuals from a range of arts and educational organisations in Gothenburg in the surrounding Västra Göteland region.

We are inviting organisations regionally, nationally and internationally to sign up to the Manifesto. Please contact Adndan Abdul Ghani or Denise Langridge Mellion by e-mail: Adnan.Abdul.Ghani@rb.se or denise.mellion@akademinvaland.gu.se.

A double-quoted world

Blog entry on Art.School.Differences: bit.ly/a_s_d; 31.10.2017

Paola De Martin,

—

“I really don‘t like words like ‘artist’, or ‘integrity’ or ‘courage’ or ‘nobility’. I have a kind of distrust of all these words, because I don’t really know what they mean, any more than I really know what such words as ‘democracy’ or ‘peace’ or ‘pace-loving’ or ‘warlike’ or ‘integration’ mean. […] The terrible thing is that the reality behind these words depends ultimately on what the human being (meaning every single one of us) believes to be real. The terrible thing is that the reality behind all these words depends on choices one has got to make, for ever and ever and ever, every day.” (James Baldwin)

—

Introduction

In November 2016 I was invited to hold a workshop (for the description refer to PARCOURS) for the Final Symposium of Art.School.Differences Because it’s 2016. Challenging inclusion and exclusion at Swiss art schools. I presented and worked with material from my ongoing PhD-research (run-time: Sept. 2014–2019). For this workshop I emphazised the epistemic phenomenon I call “a double-quoted world”. The title of my PhD-research is Give us a break! On the taste-biography of designers featuring a working class background in metropolitan Zurich (1970–2010). Interviews with designers are the primary oral sources of my work – designers form different subfields of design, born between the late 1940s and the early 1990s. Some have the Swiss passport, some don’t, but that’s not the main question here, neither the difference made by sex, gender and race. Although my intersectional analysis does take different axes of discrimination into account, my interest focuses on what the interviewees have in common: a pronounced social upward mobility from the lower classes of society into the field of design. I combine the oral sources with visual material mentioned in the interviews or handed out to me by the interviewees. The centre of my interest is the question: What does it mean to become a designer, when socialized in the working classes during the era of neo-liberalism in Zurich? This includes also asking: what does this mean to me – since I feature this “background” too – ? I put “background” between double-quotes, because I actually don’t like to use the term in my context so much anymore. As I realized during the research process and will show below, former working class cultures and spaces are an important source of inspiration for designers, and for this reason working class attitudes morphed into a stunning present of our designed “foreground”. How can you possibly get along within this transformation when moving upward form the working classes? In what ways can you possibly move upward? How can these possibilities be described objectively, i.e. without mystifying these paths?

In my analysis, the collected oral histories function like special lenses that allow us to answer these questions and to understand the overwhelming aesthetic impact of social life. The phenomenon of “a double-quoted world” shows how designers with working class background deconstruct categories of aesthetic quality, such as “formalism”, “reductionism”, “functionalism”, etc. The common sense of good taste takes these categories as universal, and not as socially bound ones. Two dimensions of my analytical compass turned out to be useful, when arguing against the common sense of universalism in good taste. First, the historical, diachronic dimension, i.e. the continuities and discontinuities in the relationship between the milieus of the working classes and the field of design. Second, the sociological, synchronous dimension: i.e. the quality of this relationship in our post-modern, neoliberal or globalized present. Both dimensions are also interwoven in this blog entry. Now, before addressing the topic of my workshop, I will first provide an outline of my research in which it is situated.

Neo-liberalism, the working classes and the field of design in Zurich

Since the late 1970s Zurich’s social structure has undergone a massive change. In this respect, Zurich, the hot spot of my local case study, is comparable to other cities. When presenting my research in an international context, I often hear similar stories like the ones I present here, from London, Izmir, Copenhagen, Toronto, Warsaw, New York or even Ahmedabad and Saigon. What characterizes the change is first the decline of huge productive infrastructures of material labour – in Zurich for example the machine construction industries in the neighbourhood of Zurich-Oerlikon, the industrial milk production factories, the turbine and the detergent industries in the Zurich Industriequartier, the textile industry in Zurich Altstetten, the huge beer industry at Zurich’s riverside of the Limmat, the industrial paper mills at Zurich’s riverside of the Sihl – and second the gentrification of these areas, their social cleansing and takeover by what is called “immaterial labour” (Lazzarato, 1996). Zurich, coined “Rotes Zurich” – meaning the “red city” of the interwar period, a former socialist city with a strong worker’s presence and representation rooted in the socialist movement – is now well known as a centre for finance, higher education, insurance, IT and art & design with international reputation. Social democrats and the green party are representing the majority of the voters in the city’s executive, but their red-green rule is almost completely middle class based today. In the meantime, also the student body of the art & design school has changed. The former Kunstgewerbeschule deliberately attracted worker’s and craftsmen’s sons during the interwar period (not so much daughters, then) – I thereby think of iconic figures like Gottfried Honegger or Richard Paul Lohse. During the Cold War and the golden decades of Keynesian welfare, the school was still quite open to descendants of the skilled workers or craftsmen, such as Willy Guhl or Franco Clivio, for example. Today, due to Bologna reforms and the academization of the Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK) – merger of the major branches of the Zurich educational art institutions since 2007 – the student body of the design department has become similar to the one of the humanities in Swiss universities, such as the University of Zurich. It is dominated by middle or upper middle class adherents, whose parents are well appointed with cultural capital. The loss of talent and potential on the paths from lower classes to higher education is diagnosed by social historians and sociologists as the effect of manifold practices of discrimination that upward-movers must encounter along their way; the metaphor of a “leaky pipeline” is used to illustrate this. There is quite a wide range of scholarly work about this effect. In Switzerland, especially Margrit Stamm’s research stands out (Stamm 2016). None of the studies, whatsoever, look closer at the field of design in Switzerland, with the outstanding exception of the Art.School.Differences project.

And what does it mean to become a designer, when socialized in a working class that has almost disappeared? What did it mean for me? When studying textile design in the 1990s at the Schule für Gestaltung Zurich (today: ZHdK) and even more when being a practitioner, I was first overwhelmed by the way my professors and my peers embraced the new empty post-industrial spaces, by how they turned them quickly and enthusiastically into studios, party locations, art spaces and lofts. Born 1965, I rank among a generation that still can recur to the memory of tattoos, soccer, boxing, bodybuilding, big cars, bling-bling, pop-music, precarious work, physical production inside industrial spaces, transgressive styles and sexually overemphasized attitudes as solely belonging to the lower classes. This radically changed during the late 1980s and early 1990s. I was electrified by the general playfulness and productivity in adopting former modes of lifestyle from the workers, be it in a more sublime or in a more carnivalesque way.

But I also was irritated: Why where designers making fun of the poor? Why where they making poor cultures more sublime, as if poor peoples were the raw material for the real virtue of style? What was so great about this dirty emptiness, this sudden silence of the machine age? What would all the unskilled people do for a living, when all these industries disappeared? So, very soon, my bewilderment mutated into confusion, and confusion into an intangible shame about my real worker’s child past. The French intellectual and sociologist Didier Eribon, in his wonderful sociological self-analysis Retour à Reims calls this kind of shame “social shame” because of its rather political than psychological implications. Being a worker’s child himself and gay, Eribon highlights the fact that in the era of neo-liberalism it was so much easier for him to reject in public the imposition of his sexual than of his “social shame” (Eribon 2016, 19–20). Both deal with the limitations of normativity, one with the heterosexual and the other with the middle class normativity, but the latter is so much less discussed and debated – maybe because it is a new phenomenon we still have to reflect? I can say for sure that in Zurich from the late 1970s on I began to feel my lower class past becoming the loser’s past. But this was an incredibly quick and complex transformation, too tricky to keep up consciously since I was merely a child and teenager then. Talking with Karl Marx, I was „alienated“ from the historical context that shaped my shame (Marx 1957ff., vol. 3, 72 and vol. 40, 512). To survive the changes I displaced the consciousness for being conceived as a neoliberal loser. I displaced the same consciousness for my parents and their friends, and the children of their friends. That was not as bad as it may sound, alienation can be very dazzling. In fact, only today I can see clearly that I was yet very much attracted by the dazzling field of design because of its alienating, illusionary and ahistorical aura.

“Illusio” and other useful terms – a brief excurse into sociology and Zurich’s design scene

The terms “rupture“, “habitus”, “illusio“ etc., that I like to use, are sociological terms, coined first by Pierre Bourdieu and adapted from other scholars ever since, to whom I owe my greatest respect. They helped me to understand the deep political and historical implication of my “social shame” in the design field. A short explanation of these terms situated in the context of Zurich might help the readers, too.

“Illusio“ after Pierre Bourdieu means the faith in the reality of the game you are playing in a very specific professional “field”. Every “field”, e.g. “the field of education”, “the field of the arts”, “the field of science” or the “field of economy” etc., creates its own “illusio”. “Illusio” therefore is the faith or belief that the inputs and outputs of what is at stake are of value (Bourdieu 1996, especially 330–336). For the field of design – or, more precisely, the subfield of design in the greater field of the arts – the “illusio” creates the deep belief that what talented designers really do are beautiful, meaningful and functioning things, and that it is really worth putting all your skills and ambitions to reach this aim. Bourdieu’s concept of “illusio” is helpful to investigate the sober facts behind it. Only then you see how the social structure of inequality within the field is being shaped – beyond the veil, so to speak, of all agents. Inside the field of design and beyond the veil of its “illusio” lies the sober fact that what talented designers do are status objects – and status knowledge of Swiss society is therefore the crucial knowledge for a successful designer in Zurich.

Because the recognition of this factual reality behind the veil would somehow spoil the “illusio”, it must be displaced. But how is this displacement working, and why is it working so well? On a general level, these questions were the driving force behind all endeavours of Bourdieu’s sociology. One of my students once said, after reading Bourdieu in my class, that talking explicitly about the making of status with designers is like talking about what you do while you are seducing somebody. Following her striking remark, one could say that designers are trained to make status differences look sexy. To understand how and why the displacement of status knowledge is working so well, and in Zurich’s design scene it is working extremely well, the concept of “habitus” is helpful. “Habitus” is a set of practices and judgements that are conceived by the common sense to be quite natural. For example, one of the experts of the field, I also interviewed, said that it seems quite natural that a working class child would never become a designer. This naturalization is the effect of a forgotten history under the practical shortage of everyday life, a history that is full of status angst, social struggles and power games. Instead of being outspoken and part of the common design narration in Zurich, these histories are embodied, passed over by attitudes and judgements, performed and re-enacted by the uses of language and by institutional rules from generation to generation – without reflection.

A “rupture“ or “break” in sociological terms defines a moment in life, when specific strategies that you have internalized as a child and teenager in your milieu – your quasi-natural “habitus” – all of a sudden become disfunctional under other circumstances. This “rupture” can be caused by a change of the milieu and/or by a historical change of the social structure as a whole. My interviewees experience both. In fact, I found that they are “rupture” experts after making the effort to understand their statements hidden behind the narrow social limits of their speech. A “rupture” or “break” in this context doesn’t mean a physical or psychological trauma, but rather an epistemic shock. The social world doesn’t make sense in a natural way anymore, it becomes, as the title of my workshop indicates, “a double-quoted world”. It is within these “ruptures” that the forgotten histories of the social struggles in the field of design come to the surface. Some of them are very old, and date back to imperialism of free trade in the 19th century and to World War I. Some of them are younger, they relate our conflicts today to the Great Depression of the 1930s, to World War II, to the Cold War or to the economic crisis of the 1970s. I go into more detail in my dissertation and try to unveil the strong impact that these conflicts have had inside the field of design when it comes to its relationship to the working classes.

It is important to highlight that experiencing an epistemic “rupture” or “break” per se isn’t necessarily a negative experience. Social movements explicitly induce epistemic “breaks”. The feminist critique of “phallo-centrism“, the queer critique of “hetero-normativity“, the postcolonial critique of “euro-centrism“ and “white normativity” – in a very powerful and politically public manner – deconstruct the “illusio” of a naturalized social order. By doing so, they upset the deep faith of the patriarchal, heterosexual, white and western hegemony in culture. But how about class in culture, especially in the design culture of Zurich?

Seeking for appeasement – believing in design

To experience the shock of a “rupture” in a productive way it takes, first of all, reflexivity and then the support of peer groups, for this reason I call my dissertation project Give us a break! It is the attempt to regain the lost public space and the lost public terms of social thinking. I lost my peer group during the late 1970s and the 1980s when I went to high school, the first one in my family since generations and the only one of my whole working class neighbourhood. I also lost reflexivity because of the tensions that were threatening my parents, my sister and my whole milieu during the structural changes in Zurich, as I mentioned above. Today, I can clearly see that I wanted to believe in the “illusio” of the design world because it looked to me as if it was a safe realm – completely untouched by social tensions. I desperately wanted to escape from the harsh violence of the ongoing changes, and my skills and diligence allowed me to enter the world of creativity, of constructive talent and beauty as it was displayed to me in the design school: a wonderful, unspoiled, eternal and magic sphere. Religious connotations are obvious here. I believed in the universal embrace of good taste, in the complete modesty of modernist reductionism, in the unlimited longevity of sustainable design, in the ideologically boundless release given by post-modern irony, in the total approval of transgression by trash, in the socially infinite inclusion of kitsch by its campy sophistication, in craft as the truly unspoiled reference for industrious creativity, in the absolute rule of talent as the only legitimate means for success – and by doing so I learned in an absent-minded way to disdain my former working class self. But that is not all I did. In the context of neo-liberalism and postmodernism it is important to say that I also adapted myself unconsciously to a new symbolic competitiveness and scooped a most valuable resource to make ends meet: my insight into the intimate dreams of the wannabes. I did my part to provide the former industrial spaces with commodified phantoms of my own recent past.

Of course I felt that on the long run something was going terribly wrong, but I displaced this knowledge to keep going. After all, I had put so much time, energy and money to get there. Under these circumstances, being a design student with a strong connection to friends and families of my working class milieu, and even more being a practitioner was a long intensifying nightmare. A nightmare, speaking with Sigmund Freud, is not so much a horrible dream because of its horrible content, in fact, it is a horrible dream because the dream-work does not work and the truth about your wishes cannot be displaced and distorted anymore in order to keep sleeping (Freud, 1999, 578–592 and 688). Finally, this truth came through and made me wake up from somnambulism – it showed its naked face to the conscious mind, sometime around 2001: I had wanted to believe the “illusio” to stay inside the field, I had desperately embodied the role of the wannabe to stay inside, at any price – be it social self-disdain, be it economical and symbolic self-exploitation.

Waking up caused a severe epistemic and social “break” with the realm of design. The years before I had been back and forth in the process of awareness building about the “illusio” of the design scene, but once I allowed myself to see and reflect it, the whole design scene was definitely disenchanted. The universality of good taste became a double-quoted “universality“, modernist reductionism became only “so to speak modest“, sustainable design “pseudo long-lived“ and so on, but most important: the absolute rule of talent as the only legitimate means for success became a very relative and arbitrary rule. In other words, my new sobriety opened the view to highly distinctive, but seemingly invisible class-bound practices and class-bound judgements inside the design field.

This sober gaze was first a shock and became only fruitful with the further steps I took: my studies in economic and social history and art history at the University of Zurich and my dissertation supported by the ETH Zurich. When talking to the designers that are still in the field I am very much aware that my outside position is a now privileged one. Due to my distance as a scholar and to my sense for the special sound of the former worker’s dreams and nightmares inside the design field, I can crystalize class limits that insiders often cannot, even if they wanted. I am confronted with reflexion as well as with the limits of reflexion in the interviews, limits that may seem individually motivated. When considering the existential threat that a disenchanted awareness of the game can be for these agents, I see the limits of speech as manifestations of the narrow limits of open debates about class boundaries inside the field. Thus, I would follow Pierre Bourdieu who says that the practical, physical sense for social borders lends itself to the oblivion of limits (Bourdieu 2010, and 1987, 734). He is pointing out the fact that worker’s children eliminate themselves from highly skilled professions, because they don’t even think that these professions could be suitable for them. All my interviewees talk about the time it took them to overcome this inner gap. Numbers and statistics clearly show the quantitative surface of this habitual self-limitation in Zurich’s design field (Seefranz and Saner 2012; Saner, Vögele, and Vessely 2016). But what happens when you succeed in trespassing the line, despite of everything?

Disappearing behind the middle class mask

The practical sense of one’s place in society makes it seem quite natural that a working class child would not become a designer, like a cat, quite naturally, would not want to swim. So, once you made it nevertheless, things get very tricky. The practical, physical sense for social borders lends itself to the oblivion of limits – but only as long as you stay within the milieus of the working class and reproduce the status of your milieu in your own path. Trespassing the lines therefore means two things. First, that the oblivion is suddenly toothless and you start feeling the limitations offhand, struggling with an unknown sense of morbid strangeness. Second, that you experience the annihilating power of a middle class normativity: you do feel clearly out of place but realize that this out-placed position of yours, in the mind of everybody else accessing the field, does not exist. What does not exist cannot be recognised. This lack of recognition is the external contribution that completes the overall oblivion that trespassers overcome involuntarily. The lack of recognition from inside the field is another interesting thing. Here, once again, one could think that it is a personal attitude of some individuals that are just intellectually too lazy or not emphatic enough. Again, I rather suggest that it is a manifest articulation of the narrow limits of open debates about class boundaries, one coming from inside the field. By reading these articulations against the grain, the objective limits can be named and crystalized. Actually, a chapter of my dissertation is dedicated to the limitations in understanding my research by those who cannot possibly see the middle class normativity from within, like a fish cannot possibly feel the water, or: their own naturalized “middle class habitus” within a “middle class field”.

The denial of the existence of class boundaries inside the design field leads to a complex situation: an embedded loneliness of the “space intruders”, as Sara Ahmed calls social trespassers of all kinds (Ahmed, 2004). What is striking in all my interviews, is the fact that the interviewees are, simultaneously, completely fascinated by the “illusio” of the field, as much as they are forced to experience a “rupture” or “break” with the “illusio” that nobody else must. All of them use at some point the metaphor of a “dry sponge absorbing water” of the design world. And all of them tell me about their isolation, sometimes using positive visualizations such as “floating island”, “martian”, “hermit” or a James Bond-like “secret agent”, sometimes recurring to rather violent connotations such as “prisoner” or “hostage”. In their pronounced isolation it becomes clear that the working class intruders into Zurich’s design field cannot recognize so easily who is also wearing a middle class mask. This isolation is a hardship that some of my interviewees are even able to enjoy, but it is not the only hardship. On top of that lie discriminatory practices and humiliating judgments about their families and peers. The middle class mask is therefore a most ambivalent one: it makes it possible to resist discrimination alone by adopting a middle class “habitus”, but this implies the indignity of your working class self, and the impossibility to be recognized by others and unite in a common struggle against class discriminatory practices.

What a limitation is, after all

In my workshop I opened the reflexive space for discussions about class in design cultures. We did so by listening to the sound of sociological and historical “ruptures” I extracted from my interview transcripts. The examples were always related to very specific, visual and material objects of the Zurich design scene that I cannot display here. It was a great opportunity for me to explain the quality of inequality in Zurich to an international audience and to work with the participants through the oral surface of the quotes, trying to objectify the specificity of the empirical material.

How is it then that designers and social upward movers deconstruct the normativity of aesthetic categories today? I ask back – deriving the leitmotifs from the rich quotes provided by the interviewees, from their stream of unconscious and conscious social critique, from their attitude of rejection and approval of the design world – with the following questionnaire:

• At what point is the postulation for so called “good taste” opening a forum for debates, and when is it – on the contrary – “an aesthetic euphemism for social arrogance“?

• At what point is so called “talent” honored as an aesthetic potential for social revision, and when – on the contrary – is the ritualized regress to talent “an excuse for social reproduction through the similarity between the well-established and the newcomers“?

• At what point are so called “social media” really social in distributing cultural capital, and when – on the contrary – are social media “making a difference that gets bigger and bigger in a very attractive way“?

• At what point is so called “reductionism” a tool for democratic design, and when – on the contrary – “a modernist mannerism completely detached from its economical implication”?

• At what point is so called “inspiration drawn from the working class milieus” an economic acknowledgement of the creativity of the unskilled, and when – on the contrary – is it “a re-edition of slumming practices from Victorian age“?

• At what point is so called “sustainability” a value that works also for the poorest, and when – on the contrary – “an escapist and neurotic cocooning of the worried wealthy with no political grip“?

• At what point is so called “postmodernist irony” a true chance to evade paternalism in aesthetics, and when – on the contrary – “an aesthetically controlled joke at the cost of the underprivileged“?

• At what point does the so called “academization” of design schools help our students to reflect the diverse hierarchies within the design world, and when – on the contrary – is it an „intimidating curricular set of bourgeois attitudes“?

This provisional, incomplete questionnaire is here to consider what an invisible social limit is, after all: a very fine addition of very fine points that the struggle for a better life, at the end of the day, sums up to a great divergence. Further, and inspired by James Baldwin’s opening quotation, I would say that these points in my context are “choices one has got to make, for ever and ever and ever, every day“. Behind these choices lies the “terrible reality”, which is the true cost of what you believe to be real. No wonder Baldwin, in another essay uses quotes when asking: “Who can afford to ‘improvise’, at these prices?” (Baldwin 2010, 41 and 121). I echo this quote by asking who can afford to be “creative” at these prices – in Zurich and elsewhere?

As teachers, supervisors and mentors of the future generations of working class students in design, and as curators, critics, historians and sociologists of design, we should keep in mind the specific hardship of all upward movers into the field. The structure of my questionnaire, far more than its historically contingent content, therefore, is a concrete proposal of an epistemic tool for the gate-keepers and the door-openers of the field. We can use it to recalibrate our practices and judgements when it comes to class in design culture.

References

Opening Quotation

Baldwin, James. 2010. The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity, in: The Cross of Redemption. Uncollected Writings, New York/Toronto: Pantheon Books, p. 41.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Sara. 2004. Space Invaders. Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Space. Oxford/New York: Berg.

Baldwin, James. 2010. The Cross of Redemption. Uncollected Writings, New York/Toronto: Pantheon Books.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1987. Die Feinen Unterschiede. Kritik der gesellschaftlichen Urteilskraft, transl. by Berndt Schwibs and Achim Russer, Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 2010. Distinction. A social critique on the judgement of taste, transl. by Richard Nice, with a new introduction by Tony Bennett, London: Routledge Classics.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. The Rules of Art. Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, transl. by Susan Emanuel, Maldon: Polity Press.

Eribon, Didier. 2016. Rückkehr nach Reims, transl. by Tobias Haberkorn, Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Freud, Sigmund. 1999. Die Traumdeutung. Frankfurt. a. M.: Fischer Taschenbuch.

Marx-Engels Werke. 1957ff. Vol. 1–42, Berlin/DDR: Dietz.

Lazzarato, Maurizio. 1996. Immaterial Labour, in: Virno, Paolo, Michael Hardt, Radical Thought in Italy. A Potential Politics, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, pp. 133–147.

Saner, Philippe, Sophie Vögele, and Pauline Vessely. 2016. Schlussbericht Art.School.Differences. Researching Inequalities and Normativities in the Field of Higher Art Education. Zurich: Institute for Art Education, online: https://blog.zhdk.ch/artschooldifferences/schlussbericht/ (last access: 17.10.2017).

Seefranz, Catrin, and Philippe Saner. 2012. Making Differences: Schweizer Kunsthochschulen. Explorative Vorstudie. Zurich: Institute for Art Education, online: https://blog.zhdk.ch/artschooldifferences/files/2013/11/Making_Differences_Vorstudie_Endversion.pdf (last access: 17.10.2017).

Stamm, Margrit. 2016. Arbeiterkinder an die Hochschulen! Hintergründe ihrer Aufstiegsangst, Dossier 16/2. Fribourg: Swiss Education, online: margritstamm.ch/images/Arbeiterkinder%20an%20die%20Hochschulen!.pdf (last access: 17.10.2017).

Mise en ligne du nouveau site web: Réseau Suisse de recherche sur les discriminations

Nouveau SITE WEB du SNDF/RSRD. Vous trouverez ici des informations concernant la recherche sur les discriminations en Suisse.

Le RSRD met en contact des chercheuses et chercheurs qui travaillent en Suisse sur les discriminations dans différentes disciplines. Les buts du réseau sont:

– le renforcement d’échanges inter-disciplinaires sur la recherche en discriminations,

– le développement de projets de recherche,

– l’organisation de congrès et de colloques, et

– la diffusion d’informations sur des projets de recherche en Suisse.

Are You Good Enough? The Notion of «Good Design»

THE NOTION OF «Good Design» AND ITS ROLE IN DESIGN EDUCATION

Sarah Owens

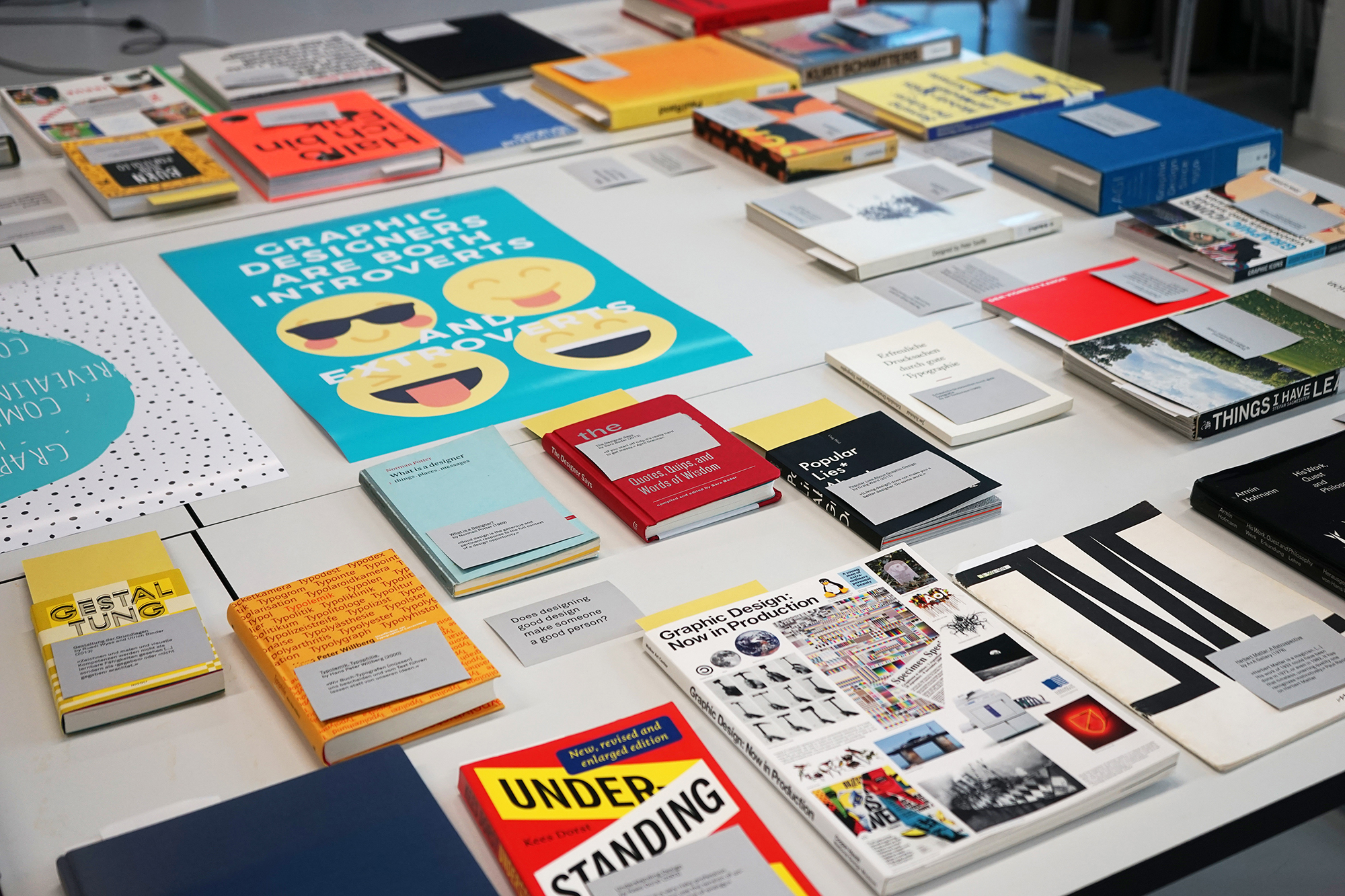

The workshop «Are You Good Enough?», held at the final Art.School.Differences Symposium (for the workshop description see PARCOURS) in November 2016, intended to galvanise questions and preliminary insights that emerged during co-research in the field of graphic design education. This research was based on the premise that the term «good design» has recently made a comeback and is becoming increasingly evident in design discourse. Good design – and by extension, the good designer – are said to possess certain characteristics that are used to explain a very diverse set of aspects ranging from aesthetic qualities to market success. The good designer is true to form, to content, and to herself or himself. Historically, the idea of good design is likely rooted in the notion of «good form», which brought with it connotations of universalism and the assumption that there is a right solution to every problem. In the more recent guise of social design, good design suggests that even economic, social and political problems may be solved through design.

The workshop was centred around an installation of books and posters highlighting statements that allude to «goodness» within the graphic design discourse, either as a marker of quality of work, of morality and behaviour, or of social engagement. It identified problematic narratives that repeatedly form the basis of life stories or anecdotes about graphic designers, condensed in types such as the «Rebel» (a designer who breaks all the rules), the «Tomboy» (a woman who becomes successful by being «one of the boys») or the «Pioneer» (a designer who «conquers» new graphic design «territory»). It also considered how graphic designers in various time periods were portrayed by others or how they portrayed themselves – for instance Peter Saville, who stated: «Graphic Design was where I wanted to belong. I wanted to be cool», in effect rendering graphic design a desirable lifestyle in which aloofness and non-mainstream savviness can contribute to being considered competent. Remarkable are also those instances in which specific personality traits are ascribed to those who are seen as good designers, as in this statement by Hans Wichmann about the Swiss designer Armin Hofmann: «His quality as a designer and teacher stems from that rare combination of deep understanding of formative aesthetic values, [and] uncompromising honesty, patience, kindness.»

Whenever a field lacks strong counter-narratives that are able to provide alternative descriptions and explanations, statements such as the above consolidate normative assumptions. In graphic design, they are able to influence ideas about who can be considered qualified or skilled, about what constitutes relevant or outstanding design, as well as impacting on notions of how design students should be educated. Such statements may become imperatives, in that they set tight boundaries as to what can be considered appropriate behaviour. They also provide a comfortable basis for categorisation and judgement as long as they remain undisputed.

A particular focus within the installation lay on the way in which the graphic design curriculum normalises certain attitudes, values and beliefs. Quotes from books on design education were juxtaposed with statements from students who reflected on entering a field that sets questionable conditions («It seems the ideal graphic design student is one who is extraordinarily ambitious, hard-working and single-minded in the sense that she or he lives for design») and positions that surface on the part of educators in situations of appraisal, for example in admissions exams («The ideal graphic design student is a blank slate, and is ready to be shaped by design education»). The resulting dialogue illustrated how graphic design students grapple with the expectations of conformance directed towards them, and revealed the pervasive (and obviously persuasive) nature of normative messages within educational settings.

The workshop aimed to leave its attendees with more questions than answers. The lively discussion surrounding the presented statements furthermore indicated that there are numerous issues demanding a more in-depth inquiry. Such inquiry can provide design educators with a basis for re-evaluating criteria and assumptions concerning good design, and hopefully will inspire graphic design history and theory to recognise alternative voices and knowledge.

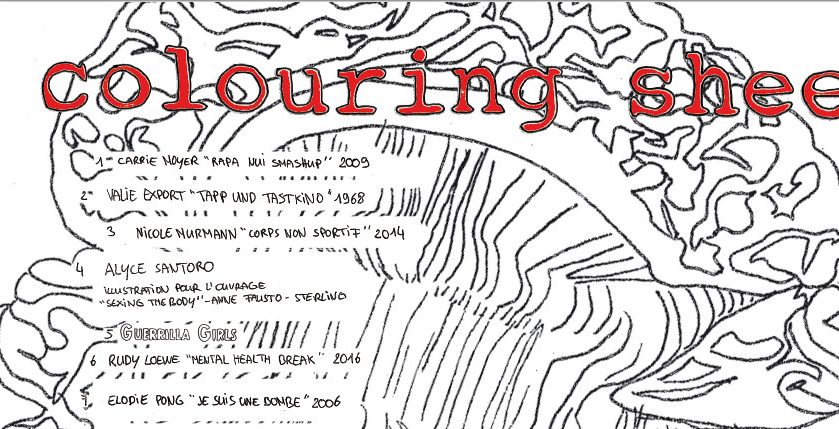

Zine Art Related Feminist Practices

ART RELATED FEMINIST PRACTICES COLOURING SHEETS.

Artists at Work from Talk to Action. How to Deviate from Normativities?

Maëlle Cornut, Marie-Antoinette Chiarenza

The ART RELATED FEMINIST PRACTICES COLOURING SHEETS resulted out of the Workshop offered at the Symposium (see PARCOURS for the workshop description). It re-staged a work situation in a fictional studio inspired by the studios of existing artists. A fifteen-minute document was played twice; the first time, as an audio file and the second time as a video file to enable a multi-layered understanding of a specific topic. Using this approach, questions such as: what are the references that we are using? How do artists research a specific issue? And what do we bring from the brain to the hands and vice versa? were collectively addressed.

WdKA makes a Difference Reader 2017

Research Project WdKA makes a Difference

WdK A makes a Difference is an action based research project interested in the possibilities of decolonial approaches within the Willem de Kooning Academy, which was conducted from

January 2015 till December 2016.

Principle investigator: Nana Adusei-Poku

Co-researchers: Teana Boston-Mammah, Jan van Heemst

Contributors: Marleen van Arendonk, Rudi Enny, Esma Moukhtar, Mark Mulder, Remko van de Pluijm, Reinaart Vanhoe

WdKA makes a Difference READER 2017

WdK makes a Difference WEBSITE

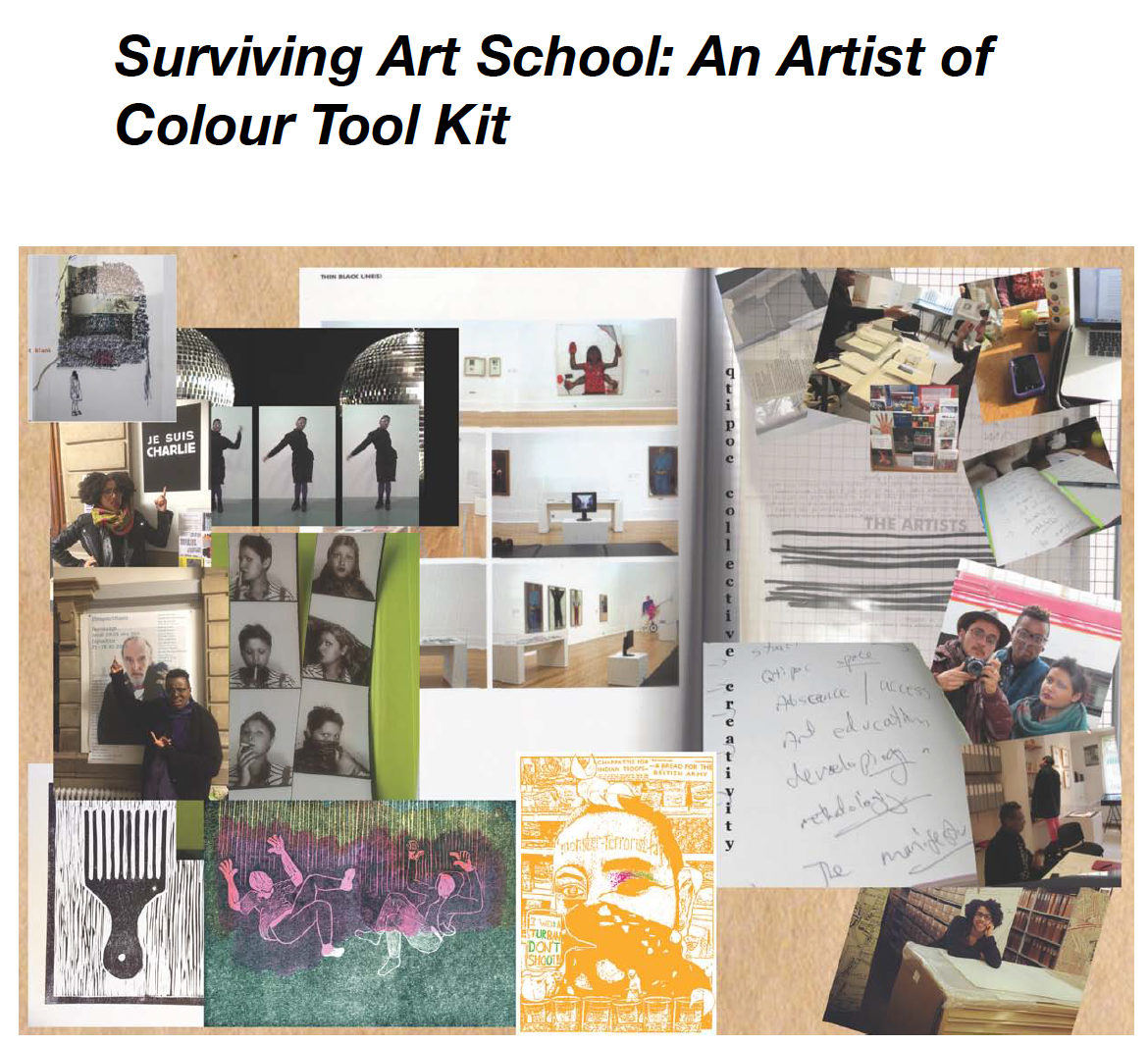

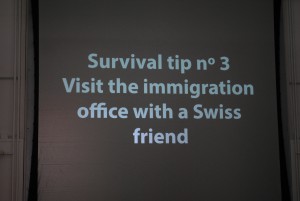

Swiss Art School Jungle

How to Survive in the Swiss Art School Jungle?

The daily micro-practices of discrimination of international students at art schools

by Coko Nuts Collective (represented by Daniel Zea, Hyunji Lee, & Andrea Nucamendi)

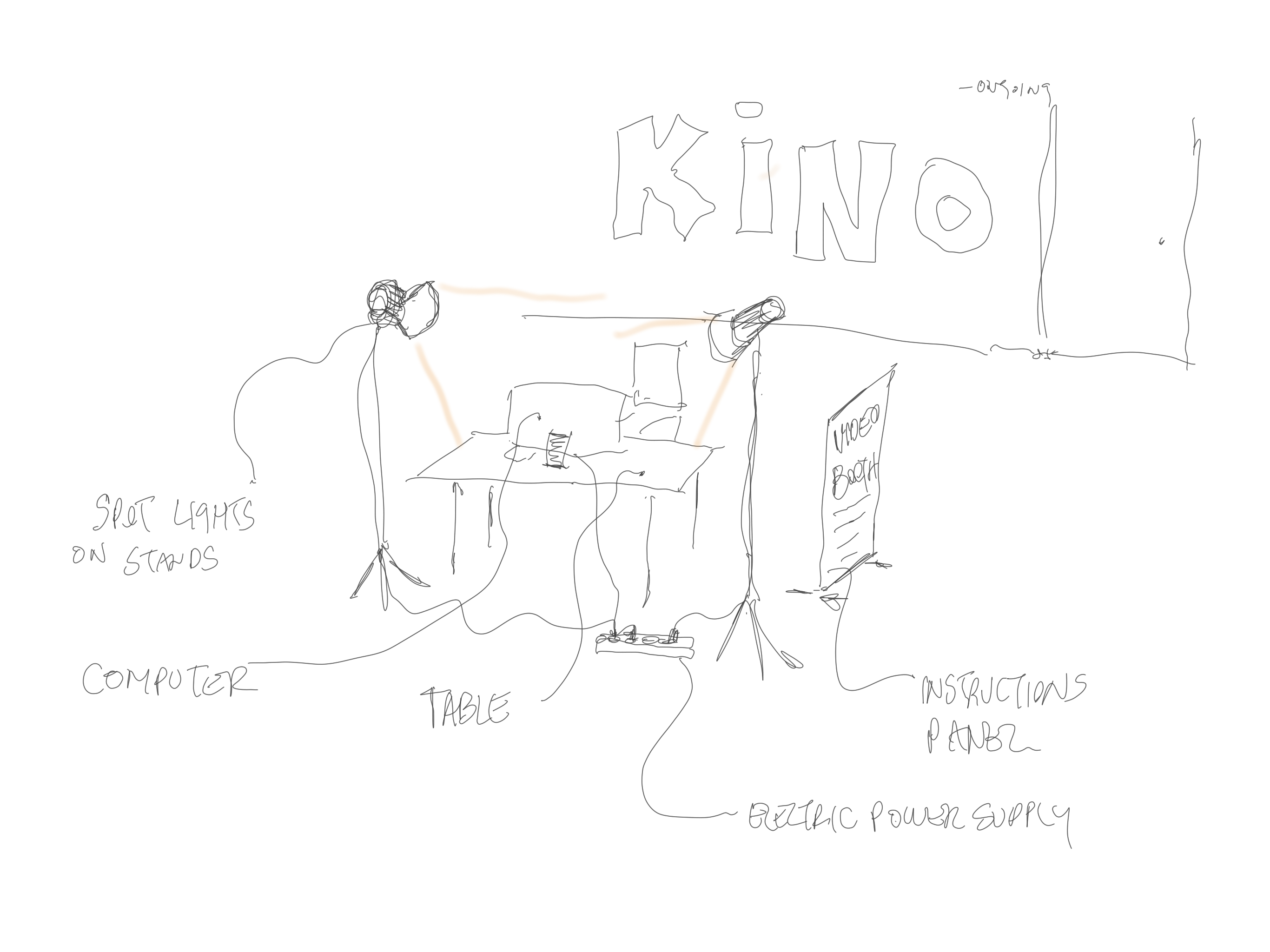

Inspired by several activist artists and collectives, as well as other art projects, the Coko Nuts collective uses real-life testimonies and a lot of humour to address inequities within art institutions and society in general. Coko Nuts questions, what are successful strategies by non-European students to deal with inequities encountered at their schools? How can these strategies be depicted in art projects? And how can a more equitable treatment of non-European students lead to a more successful internationalisation of Swiss art schools? They present a series of video interviews with foreign students who have faced exclusion, in one way or another, during their student life in Geneva’s Art Schools (HEAD – Genève & HEM Genève – Neuchâtel) in order to provide some answers and raise new questions (see also CO-RESEARCH).

During the final symposium’s PARCOURS the testimonies were shown in the Toni Kino and a VIDEO BOOTH INSTALLATION allowed people to share their own videos with the Coko Nuts Collective.

Have you experienced any exclusion or marginalization due to your diversity?

Art.School.Differences final report and statements

Le rapport final Art.School.Differences, les prises de positions des écoles partenaires et la meta-prise de position à leur sujet du comité scientifique international sont en ligne sous rapport final et prises de position.

Le chapitre 9 synthétise les conclusions, chapitre 10 rassemble les champs d’action identifées pour parvenir à une école d’art plus inclusive.

Disability inclusion

REPORT ON THE FINAL ART.SCHOOL.DIFFERENCES SYMPOSIUM by Nina Mühlemann*

I attended the Symposium ‘Because it’s 2016! Challenging inclusion and exclusion at Swiss art schools’ as someone with a strong interest both in the performing arts and in disability inclusion. Growing up as a wheelchair user in Zurich and studying English and German literature in Basel, a critical analysis of disability or its representation was never part of the curriculum alongside gender, race or sexuality, even though I longed for theoretical frameworks that included disability. Once I discovered Disability Studies and realised that this was an emerging field in the UK and the USA, I decided to pursue a Master’s degree in the UK. Currently I am writing my doctoral thesis at King’s College London about the vibrancy of disability arts in the UK. When I arrived to do my master’s degree in London in 2010, I was amazed and delighted to discover the high professional standard of disabled artists in the UK in all art fields. Often, this work gives profound insight into different ways of being in the world and how we, as a society, value them.

I was very curious to hear at the Symposium what the situation is like in Switzerland for young disabled people who are keen to become professional artists. Where do Swiss art schools stand at the moment when it comes to inclusion? What are the barriers, and how can they be removed? What kind of insight can experts give who have been working in the field or art school inclusions all over the world? What can we learn from their experiences? This report will be written from a perspective that focuses on how disability was addressed during the Symposium, and I will attempt to insert disability into some of the questions or issues that were raised during those two days.

The day at ZHdK started off with Sophie Vögele, Philippe Saner, Pauline Vessely and Carmen Mörsch presenting their research on social differences in the admission process at Swiss art schools. The participating schools were the Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK), the Haute école d’art et de design – Genève (HEAD – Genève) and the Haute école de musique Genève – Neuchâtel (HEM).

The researchers took a report from the UK as a starting point, Jackie McManus’ study ‘Art for a Few’, which stated that art schools are for the privileged, people who are white and middle-class. The researchers were then interested to find out how art schools in Switzerland recruit, evaluate and select their candidates – what is the ‘ideal student’ in this process, and furthermore, how do students cope with the idea of this ‘ideal student’? Are there any mechanisms that effect the exclusion of very specific social groups? In their results, they found, for example, that more and more students of artistic disciplines have at least one parent with a university degree and come from culturally privileged families.

When it came to presenting fields of tensions within the selection process at art schools, the group stated that the criteria this process is based on is often very vague, which in theory could open up a space for the unexpected, for students who are ‘other’ – yet, this was not what the researchers found, on the contrary, a normative identity seems to remain a requirement.

When it comes to disability, in particular, one finding was difficult to swallow: During the open days at ZHdK for the degrees in theatre and dance, it has been stated very openly by the art school that a normative physicality and mental wellbeing is a requirement for admission. This requirement is stated publicly, which perhaps shows that discrimination of disabled people is still something that happens very openly in Switzerland. In other parts of the assessment it is also made clear that it is a requirement to be in full physical and mental health to be able to do this degree. Why is this still acceptable? The title of the evening was after all ‘Because it’s 2016!’, and that such open discrimination in 2016 is still possible made me feel furious. It also made me feel extremely grateful that this research project and the rigorous work of the researchers was there to uncover this discrimination, put it on the table and offer it up for discussion.

Many of the rigorous requirements in traditional arts training are tied to able-bodiedness – Can students practice day and night? Can they mould their bodies for their artform in a way that makes their identity disappear? Can they adapt themselves and their artwork to whatever ideal their teachers or the market demands from them? All forms of perceived difference that deviate from a fabricated normative ideal are seen automatically as lesser, as not good enough.

Not demanding compulsory able-bodiedness from students would mean to let them mould the artform so that it suits their bodies and competences, not the other way around. As disabled artists in the US and in the UK have shown repeatedly, opening up art forms – dance, theatre, visual arts, performance – to disabled bodies can enrich these art forms and release new creative possibilities. This does not mean that whole curricula have to be changed, but it does demand a more flexible approach towards assessing students’ competences and a willingness to imagine a potential that goes beyond the already familiar from teachers and admission officers. It requires a willingness of teachers to be taught by their students sometimes, too.

The researchers then gave us a little preview of the reader, which will be available from early 2017. It was created based on the findings of their research, and texts in English, German and French. The reader will have five volumes and one of them focuses on disability inclusion. The reader was created as a tool and resource for teaching, but also as a support for negotiations that happen within the sector of higher education.

After this first insight, we heard the first two keynotes, which were both fantastic. First on was Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández, with a talk entitled ‘Creation, Participation, and the Political Life of Cultural Production’. It centred around the idea of cultural production, and how it can be used. Within this rhetoric, artistic forms are understood as processes, taking material conditions, cultural contexts and social circumstances into account. What cultural production is currently granted the status of ‘the arts’? Gaztambide-Fernández explored how particular conditions are needed to achieve this status, and he wondered whether it was possible for us, as a society, to relocate or resignify what we mean by the arts and to destabilise the hierarchy that often structures what is seen as arts and what is not.

Gaztambide-Fernández explained that traditionally, but also in a neoliberal context specifically, the arts are often framed as a substance or medicine that can be injected and has transformative qualities, as a tool to civilise citizens and especially young people. As a result, what we understand as ‘the arts’ becomes trapped by its own rhetoric, being seen as something that maintains ‘European civilization’, or in other words, European cultural supremacy.

Although Gaztambide-Fernández did not mention this, the injection of arts as ‘medicine’ is highly visible within a disability context where art is often seen as a form of rehabilitation or therapy. While art of course can be therapeutic, in these contexts the produced art is often seen as of little value, simply because it was produced as a means of therapy.

The second keynote was by Nana Adusei-Poku, entitled ‘Everyone Has to Learn Everything!’. She was talking about her own experience as a researcher and teacher within higher education at Rotterdam University of Applied Science. She explained that while the general population of Rotterdam consists of 55% people of colour and 45% white people, she does not see this population reflected in her class rooms. Adusei-Poku introduced me to the concept of racial time with the example that up until some decades ago, books were first given to white schools and then handed down to black schools. This delay produced a knowledge gap. Currently, there is another knowledge gap produced by racial time at schools, as the core curriculum is always based on white history, while black history is deemed ‘elective’ and absent in the canon. Adusei-Poku sees her work as decolonising work and acknowledged that this work is uncomfortable as it is destabilizing hierarchies, and as such is often met with resistance.

Adusei-Poku further talked about her experience of caring for her white students as a black educator and the emotional labour that comes from discussing whiteness with white people. This kind of emotional work that educators take on themselves is extremely necessary and, at the same time, under-appreciated and devalued.

While Adusei-Poku voiced some frustrations about her role, as most often she can only reach those who are already willing to listen, her talk also showed how important it is for inclusion not only to happen on a student level, but also on a staff level, in order to provide an inclusive and stimulating environment to all students. To see some of the work Adusei-Poku has done and what she has achieved together with her students and allies was extremely inspiring and left me feeling very positive.

What followed after these two wonderful keynotes was somewhat disheartening and also a clear example of the resistance Adusei-Poku mentioned that her work towards inclusion is often met with.

It was now time for three directorate-members of the art schools participating in the study to respond to the findings of the report. Hartmut Wickert of ZHdK, Lysianne Léchot Hirt of HEAD – Genève and Xavier Bouvier of HEM Genève-Neuchatel started the discussion on a defiant note, with Bouvier stating that everything he was going to say would get deconstructed anyway as he was seen as ‘the voice of power’. Wickert expressed that he found the fields of action identified in the report disappointing and unsatisfying, as the school had to adhere to strict frameworks already given and that enacting change would be difficult. Léchot Hirt was prepared to claim more responsibility for the findings of the study in her answer, saying that results came as a shock to her as the institution considers itself as innovative, and the study proved a rigidity and a predictability of the institution that she did not realize was there.

In their responses, all three educators repeatedly brought up the marketplace and the standard the market expects from absolvents of art schools, suggesting implicitly that the market demands certain kinds of people, especially ones that are already privileged. Some statements also made it seem as if rigid policies implemented on a cantonal and national level made it next to impossible for the schools themselves to evoke change. The three educators also questioned the methodology of the study, which seemed to serve as a distraction to respond to the real issues the report had pointed out. As the discussion progressed it became clear that many in the audience, myself included, were dismayed by the reaction of the gatekeepers of these three institutions.

I appreciate the gatekeeper’s presence at the discussion, because this is not something that can be taken for granted, and it shows a readiness to listen. Léchot Hirt also stayed for most of the 2-day symposium, which shows a willingness to learn about the issues discussed and openness for change. I am also aware that there well may be instances where a lack of funding or rigidly imposed frameworks make it difficult for the schools to enact change. However, as I mentioned at the beginning of the post, when it comes to disability there has been the case of such discouragement towards disabled students that has come from the ZHdK itself that I know there are profound misunderstandings and shortcomings which need to be addressed urgently.

In the discussion Wickert brought up DisAbility on Stage as an example where a step towards inclusion had already been taken, a research project at ZHdK which “aims to foster a discourse on dis/ability within Swiss Art Schools and universities by questioning models of dis/ability in theoretical reflection, performing practice and education. It brings together a unique team with members from national universities, art schools, dance and theater companies, and festivals, by including the three major Swiss language regions.” I am very excited about this project, but also dubious whether it is enough to readdress the systematic exclusions of disabled performers that have been happening for decades at Swiss art schools. DisAbility on Stage aims to bring disabled artists and art students together to foster understanding and collaboration, but it does not change the fact that disabled students are discouraged to apply to ZHdK.

I voiced this concern in the discussion and was told that the curricula of the art programmes at ZHdK could not be changed overnight and yet again that the art schools depend on applicants who the market has a demand for. Several people furiously spoke out against this response – as someone pointed out, justifying your exclusions and ableism with the fact that the same thing is happening on ‘the market’ is not good enough, especially as other countries such as the UK have shown that a) including disabled students does not require a complete change of the curricula and b) there is a market for disabled artists.

Once the discussion round was over I felt angry and disappointed, but also hopeful and, once again grateful for the people who did this research and organized this symposium to address the inequalities their research brought to light. A very energetic performance by Ntando Cele finished the day on a quite provocative note – Ntando slipped into different roles and the show encompassed a monologue chock-full of dark humour and punk songs performed live on stage, all the while addressing the systemic racism present in the art world, but also in Switzerland generally.

This full-on day left me quite exhausted for the 9am start on Saturday, but the two keynotes were once again fascinating: Cornelia Bartsch talked about the gendered and queer spaces she found in the music of Bach, and the music included in her presentation felt wonderfully soothing after the highly emotional experiences on the day before. Rena Onat and Bahareh Sharifi discussed the current situation in Germany, where a recent political decision to let refugees into the country was accompanied with funding of cultural education for those refugees, even though a further art school education is most of the time not a possibility for them. Furthermore, they brought in examples of artists in Germany and elsewhere who have experienced racism and used these experiences to think through structures of support.

After the two keynotes, there was a parcours where different rooms invited us to engage further with some of the questions and issues raised in the keynotes and presentations. While I enjoyed the two rooms I visited, I really needed the time to properly digest all the input from the two days, and more importantly, to connect with other people who attended the symposium. This was one of the most gratifying insights from the symposium: It opened up a room where alliances could be voiced and built. Fields that work with identity can sometimes be a little inward looking. In disability studies, we sometimes think about disability without taking other markers of difference or intersectionality into account when in reality, it can be so productive to look outwards, to share our insights and to listen to the insights of others.

In the afternoon, Melissa Steyn gave the final keynote about the important decolonizing work she has done within education in South Africa, and then Adusei-Poku, Jackie McManus, Olivier Moeschler, Ruth Sonderegger, Melissa Steyn and Ulf Wuggenig in their capacities as International Advisory Board members did a conference wrap-up. They highlighted again how important this work of the report is, and that the resistance that was shown towards it showed how necessary it was to get the ball rolling. I was very glad that I attended the symposium, even if it was upsetting for me to be confronted with the findings of the report. I left the symposium on a hopeful note, feeling inspired about all the fascinating research I heard about, especially as I think it will have an impact on the way I approach the classrooms I am teaching in. I am very excited for the readers to be published and hope that this research has been an important milestone which will evoke change at Swiss art schools and beyond.

*Nina Mühlemann is a doctoral student and Teaching Assistant at King’s College London at the Department for English Literature. Her focus is to analyse works of disabled artists and compare them to mainstream representations of disability. The title of her thesis is ‘Beyond the Superhuman: Performing Disability Arts Around London 2012’.

I’M HERE AND I’M BLACK, BUT I’M NOT HERE TO BE BLACK

ART.SCHOOL.DIFFERENCES: REPORT ON THE FINAL SYMPOSIUM by Quentin Delval*

Arriving at the Toni Areal after a long day and a longish train ride, I wasn’t in top form when I entered the Hörsaal 1 around 7:15pm. But the setting instantly refreshed me. Attendees were engaged in an intense discussion. “So you’re basically saying you can’t improve living conditions of minority students because that’s not what the market wants, even though you’re part of what creates that market?” was an attendee asking, the microphone in her hands. An art school representative sitting on stage had just explained to the audience that schools depend on what the “market” wants, in terms of student output. “The reality is that we depend on that”, he said, “so it is a bit more complex than just changing curriculum and practices”. He wouldn’t get away with such a “chicken and egg” contradictory stance. I heard someone whisper “so we don’t end colonialist thinking because it expects us not to?”. I raised an eyebrow. Art.School.Differences, you had my attention.

The conversation revolving around how to circumvent institutional inertia (“of course we need to change things, and of course we can’t wait until society’s ready, but we need to do it the smart way”, i.e. not now, not radically) was brought to a halt by the categorical imperative of the clock. But it was only to give us time to attend the next part of the evening, a performance that would show exactly why Art is a necessary part of thinking and changing (minds about) inequalities. Half part prejudice-triggering show, half part Fanon-based concert, the performance was a real chance for one to burst their little own racist bubble. Emphasizing that “I’m here and I’m black, but I’m not here to be black”, the artist also reminded us that “black people can write (books) too” and we should read them. How many books have you read, this year, that have been written by black authors?

Refreshed by the scent of smart, radical questioning emanating from this first evening, I went to sleep with a feeling of impatience for the next day.

TRANSFORMING THE GAZE

It wasn’t just out of personal need for academic brainstorming and entertainment that I appreciated this start of the week-end. One of the main challenges of equality in Universities of Applied Sciences in Switzerland today lies in the need to make contact with and convince the ones who need to be. Transforming the gaze of the people operating at key positions of the power structures. Extend the talk beyond the inner circle of the people already working in the field of equal opportunity and/or social justice. How do you convince people who, most of the time, won’t even hear the words you have to say, won’t share your definitions, perceptions of reality, and immediate interests? The second day of Art.School.Differences’ final symposium would provide ample choice of answers.

The keynotes, to start with, highlighted what certainly are major aspects of how domination is maintained, namely the illusion that it comes from a rhetoric construction one would just have to debunk in order to see equality advance, and the illusion that theoria is how you rebalance the access to the power structures of society. The focus of the talks therefore opened room for a materialist understanding of domination (in Delphy’s sense) coupled with the need of praxis spaces: the sexist and racist theories and distribution of power are the symptom of a power structure that also has to be addressed by granting access to a praxis, a collective experience, interaction, even at a local level, which empowers the individuals with more than words, and potentially changes the minds.

DECENTRALIZE YOUR ASS

And coherently enough, this is what the parcours was all about. Five hours of workshops, interactive performances, questioning discussions – and walking around the building, here getting a glimpse of ballet dancers practicing, there being caught by the red sound of a trumpet – all served the purpose of bringing your senses to your attention. Inequality is not (only) staged in the conscious mind, it is performed by all senses, by all forms of attention, and they all need their time of deconstruction and reconstruction. “What is this?” asks a performer, holding coffee beans in her hands, standing in a dark room in which selective lighting directs your attention, “what is this?”. Someone says “coffee beans” and she reacts “really? Really?”. It is true that we could have said “the direct consequence of a collusion between colonialist structures of power and neoliberal economy” (ah, are those different?), which are also alive in the other items on that table, chocolate, tea, bananas…. It is true we should decentralize our perspective if we were to understand the fabric of the worlds, both objective and subjective. It is true that what we have to decentralize is not only our minds, granting us with the comfortable feeling of having “understood” exclusion or privilege, but it is our very ass that needs to move aside. It is true we have a responsibility in giving birth to the freedom of our perception. That we have to remove our mask and stop expecting others to put one on.

Maybe it is my background in philosophy (or, as one workshop organizer emphasized, aren’t backgrounds rather foregrounds? I had spent the week reading about students with “Migrationshintergund” and that remark hit the right spot), but I found these phenomenological experiences quite on point. They were asking us to think with more than the theoretical bits we had acquired through the years, they were actually asking what thinking really was about. In another workshop, art-related feminist practices were “offered” to the attendees. One could listen to a video by Judith Butler and/or draw and/or look around the room for feminist manifestos and/or take interest in national statistics on gender inequality and/or do nothing. Which was a good revelator of our relative incapacity to seize our curiosity and be an active part of our “decentralization” – most of us were just expecting to be told about this passage from talk to action. But it was ours to build.

HOLDING POWER STRUCTURES ACCOUNTABLE