→ Druckbare PDF-Version herunterladen

Sehr geehrte Kunsthochschulen,

wir müssen Ihnen leider mitteilen, dass die studentische Kommission nach der gemäßen Ordnung festgestellt hat, dass die erforderlichen Kompetenzen für die Durchführung eines fairen Auswahlverfahrens nicht in ausreichendem Maße vorhanden sind. Der Antrag zur Weiterführung des Verfahrens ist daher abgelehnt. Die studentische Kommission begründet die Entscheidung wie folgt:

a Die Bewertungskriterien der Bewerbungsverfahren sind intransparent.

b Die Bewerbungsinformationen sind auf den Webseiten der Kunsthochschulen nicht leicht zu finden.

c Viele wichtige Bewerbungsinformationen stehen nur in deutscher Sprache zur Verfügung.

d Die Studienfächer und Studieninhalte sind überwiegend eurozentrisch geprägt.

e Viele Kunsthochschulen haben keine zugängliche Bewerbungsberatung.

f Die Bewerbungsanforderungen, besonders das Erstellen einer Bewerbungsmappe, verstärkt die Chancenungleichheit unter den Bewerber*innen.

g Das Bewerbungsverfahren ist nicht barrierefrei.

h Bewerber*innen müssen Bewerbungsgebühren zahlen.

i Die Zusammensetzung der Auswahlkommissionen ist nicht divers.

j Im Bewerbungsprozess steht den Auswahlkommissionen zu wenig Zeit zur Verfügung, um die Motivation der Bewerber*innen zu verstehen.

k In Bewerbungsgesprächen werden von den Auswahlkommissionen diskriminierende sowie machtmissbrauchende Fragen gestellt und Aussagen getätigt.

l In Bewerbungsgesprächen werden von den Auswahlkommissionen übergriffige Fragen zu Herkunft und Identität gestellt, die zu einer Exotisierung von Bewerber*innen und ihren Arbeiten führen.

m In Bewerbungsgesprächen werden von den Auswahlkommissionen unangebrachte Kommentare zu Aussehen und Bekleidung der Bewerber*innen geäußert.

n Der in Bewerbungsverfahren verwendete Begriff „künstlerisches Talent“ impliziert das Konstrukt einer ‚naturgegebenen‘ Begabung, welche unterschiedliche Voraussetzungen und Sozialisierungen von Bewerber*innen außer Acht lässt.

o In Bewerbungsverfahren wird eine westliche Ästhetik bevorzugt. Nicht-westliche Ästhetiken werden von den Auswahlkommissionen als kitschig abgewertet.

p Die Auswahlkommissionen bevorzugen Studierende, die denselben Habitus haben wie Mitglieder der Kommission.

q Die Auswahlkommissionen erwarten fachspezifisches Wissen, welches nur mit einer jahrelangen Vorbildung erlangt werden kann.

r Die Auswahlkommissionen kommunizieren kein ausführliches Feedback an die Bewerber*innen.

s Die Auswahlkommissionen begrenzen die Aufnahme von Bewerber*innen, obwohl die räumlichen und personellen Kapazitäten für mehr Studierende ausreichen würden.

t Die Mappen der Bewerber*innen werden beschädigt oder gehen verloren.

u In Bewerbungsverfahren nimmt die Diversität der Bewerber*innen mit jedem weiteren Auswahlschritt ab.

v Die Universitätsgebäude und Kurse sind nicht barrierefrei.

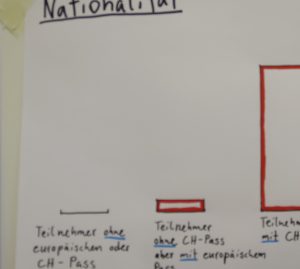

w Der Nachweis deutscher Sprachkenntnisse und die Durchführung des Unterrichts in deutscher Sprache schließt zahlreiche Bewerber*innen und Student*innen aus.

x Es werden keine kostenlosen Deutschkurse angeboten.

y Der Studienalltag der Kunsthochschulen ist mit hohen Materialkosten und großem Zeitaufwand verbunden.

z Die Ausschlüsse, die durch das Bewerbungsverfahren und den Studienalltag der Kunsthochschulen entstehen, werden nicht reflektiert, sondern ignoriert und reproduziert.

Die studentische Kommission fordert die Kunsthochschulen auf, das Auswahlverfahren und den Studienalltag auf die Ablehnungsgründe a – z zu prüfen und zu überarbeiten.

Bitte bewahren Sie diesen Bescheid auf, falls Sie ihn in den nächsten Jahren zur Vorlage bei anderen Stellen benötigen. Zweitschriften können nicht ausgestellt werden.

Mit frustrierten Grüßen,

die Studentische Kommission

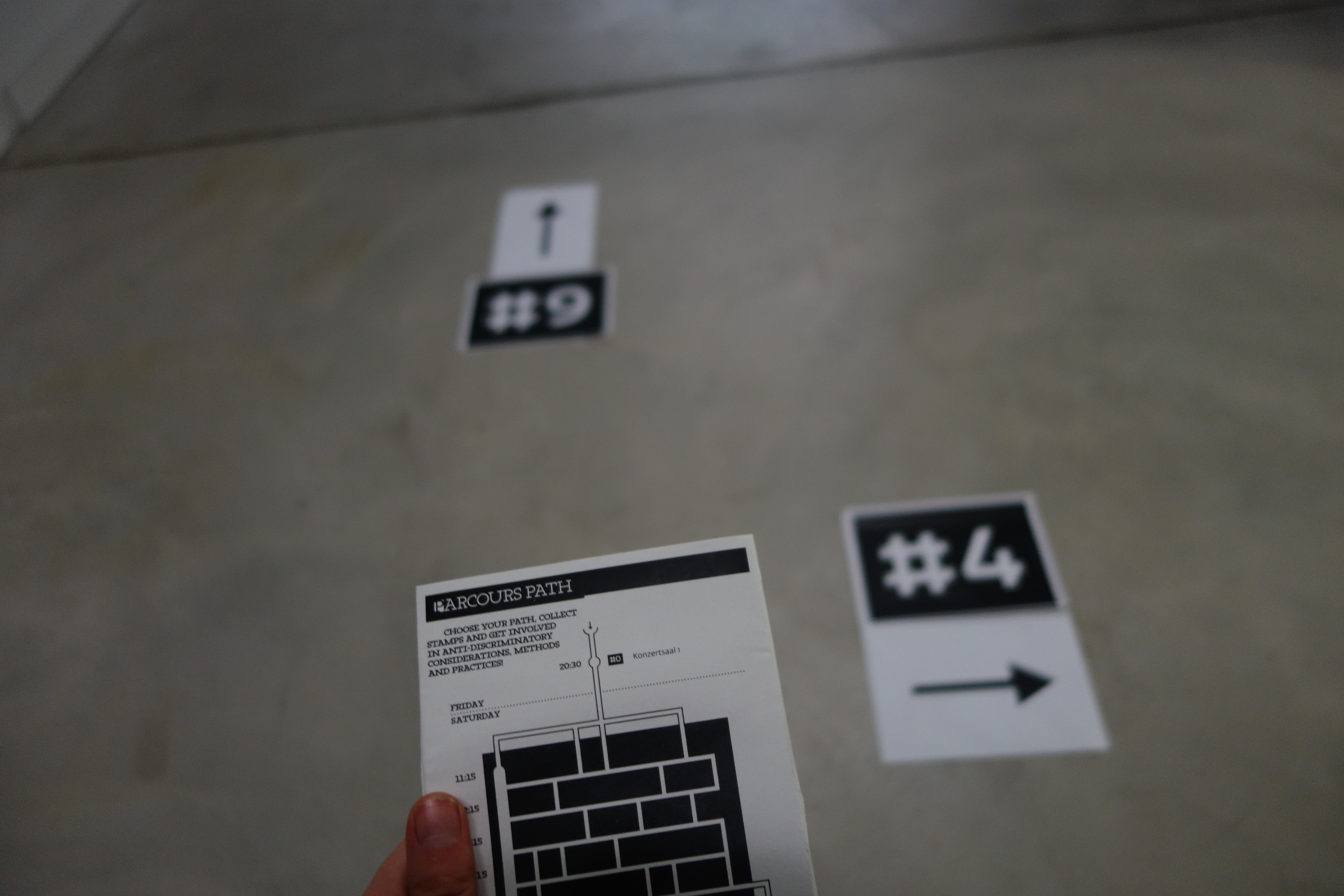

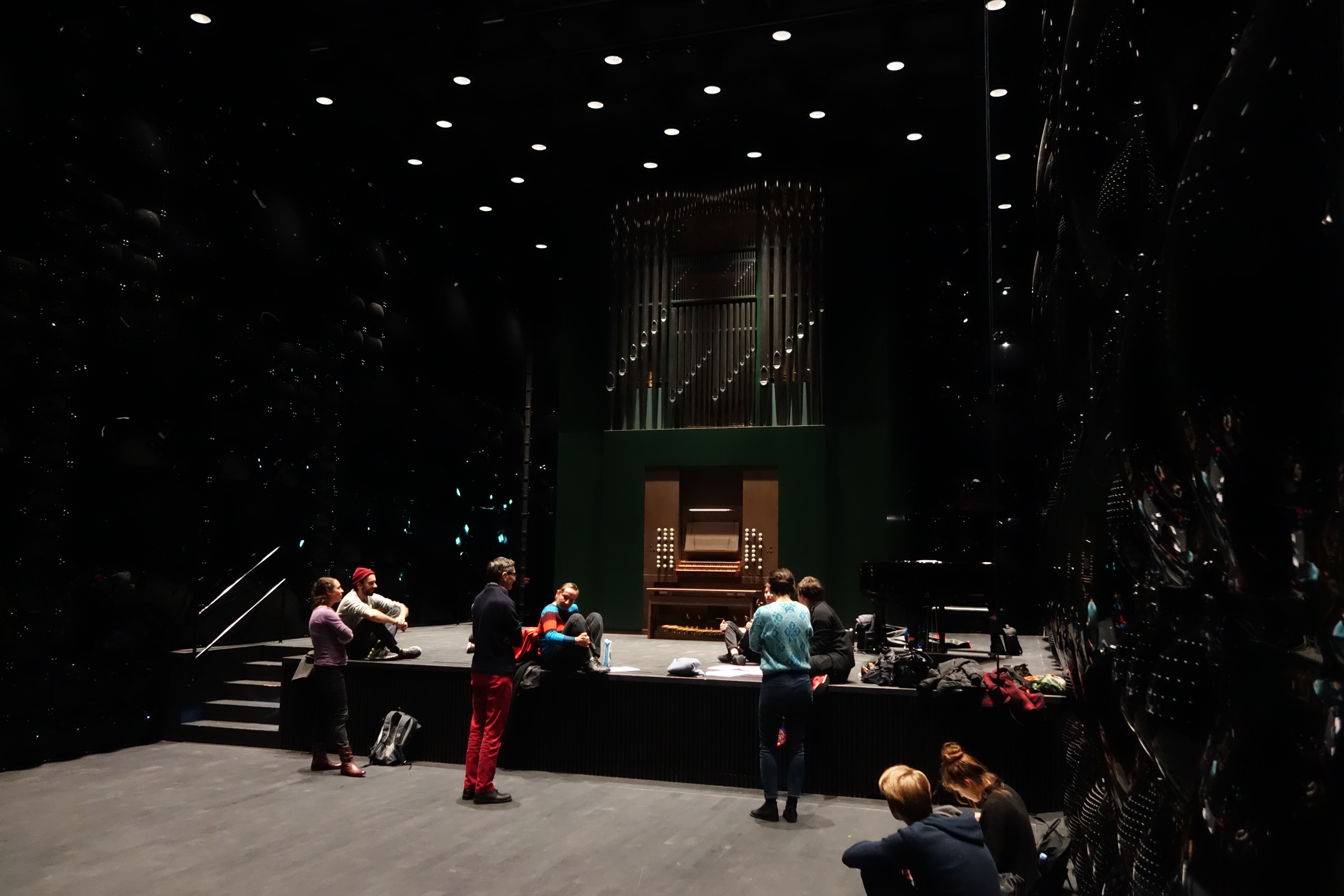

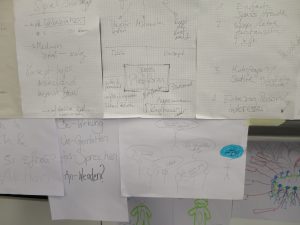

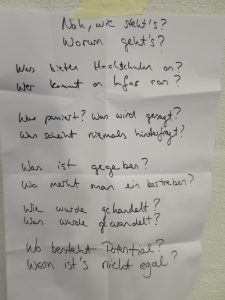

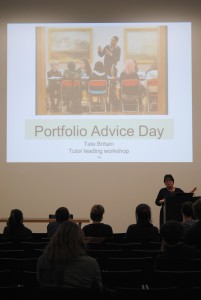

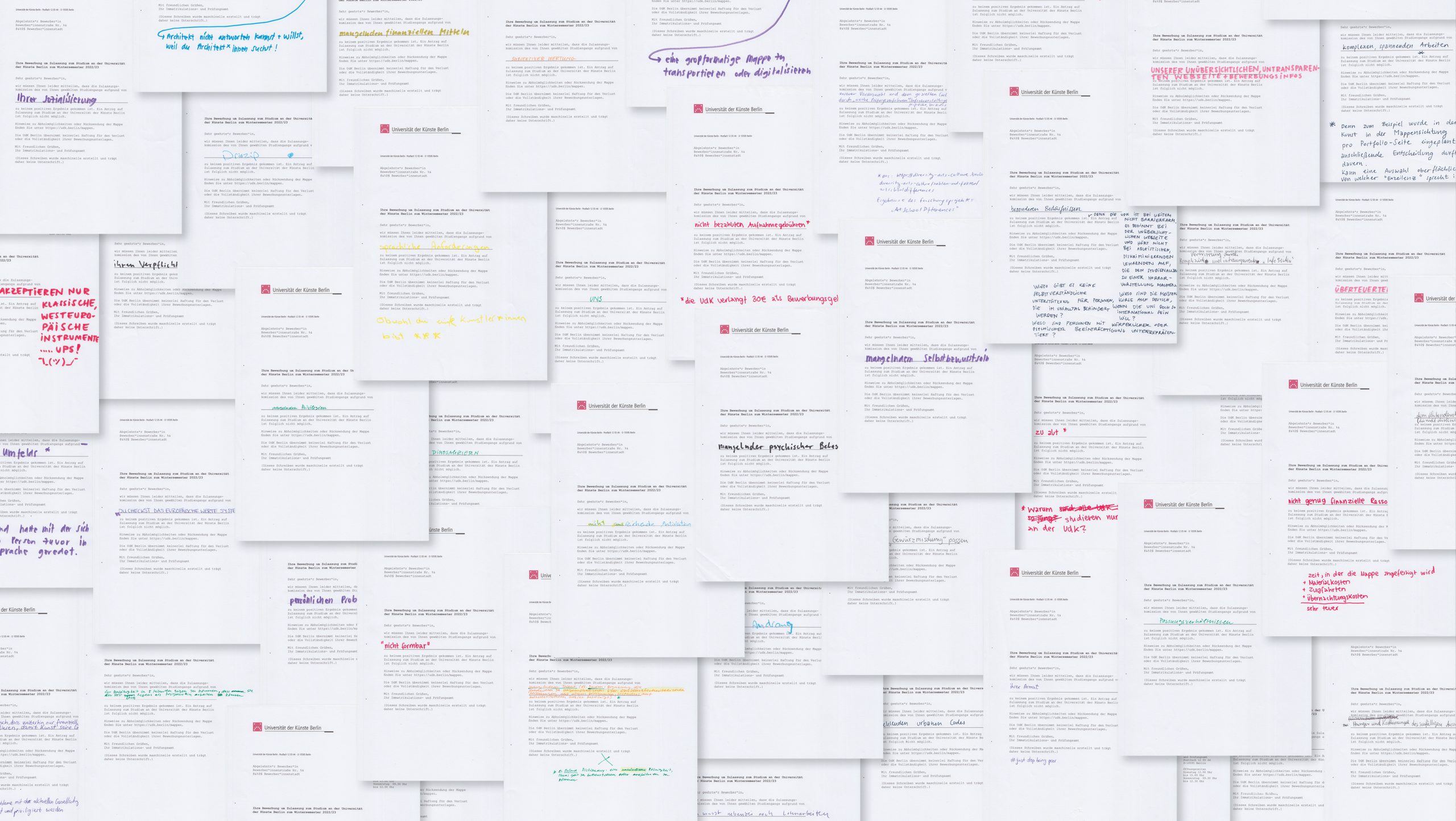

Für die zahlreichen Ausschlüsse, die Kunsthochschulen produzieren, reichen die Punkte a – z eigentlich nicht aus. Diese Sammlung an Kritikpunkten wurde im Rahmen des selbstorganisierten Blockseminars Eine Krise bekommen – Kunsthochschulen und Ausschlussmechanismen in Gesprächen, Diskussionsrunden und Workshops erarbeitet und zusammengetragen. Organisiert wurde das Seminar vom Kollektiv Eine Krise bekommen und fand im Mai 2022 im Rahmen des Studium Generales der Universität der Künste Berlin auf dem Gelände der Floating University¹ statt. Es beschäftigte sich mit den Fragen nach Ausgrenzungen und Diskriminierungen vor und nach der Aufnahme in die imposanten Gemäuer der Kunsthochschulen. Welche Erwartungen werden selbstverständlich an Bewerber*innen und Studierende gestellt? Wer kann diese überhaupt erfüllen? Wie stellen sich die Universitäten nach außen hin dar und wie erleben wir die Realität?

![[Bild 1: Seminarprogramm „Eine Krise bekommen – Kunsthochschulen und Ausschlussmechanismen“. Bild: Eine Krise bekommen]](https://blog.zhdk.ch/artschooldifferences/files/2023/02/Programm_Kunsthochschulen-und-Ausschlussmechanismen.png)

[Bild 1: Seminarprogramm „Eine Krise bekommen – Kunsthochschulen und Ausschlussmechanismen“. Bild: Eine Krise bekommen]

Das Seminar entstand aus dem Bedürfnis, Perspektiven zu diskutieren, die wir in unserem Studium an der Kunsthochschule vermisst haben. Warum wird nur über das Prestige der Zugelassenen und die Erfolge der Dozierenden gesprochen, aber viel zu selten über jene, denen die Zugänge zu diesen Institutionen und ihren Vorteilen verwehrt werden?

Schon in vorigen Lehrformaten legten wir Wert darauf, persönliche Erfahrungen in ihren strukturellen Bedingungen zu verorten und gemeinsam Kritik zu entwickeln. Um die Ausschlussmechanismen der Universität überhaupt zu erkennen, kommt man nicht daran vorbei, die Idee einer sogenannten künstlerischen Eignung infrage zu stellen. Denn der bei den Aufnahmeverfahren und im Studium produzierte und erwartete künstlerische Kanon zeigt sich in der Wertschätzung bestimmter künstlerischer, musikalischer, gestalterischer Stile und der Abwertung anderer Ausdrucksweisen. Aber auch in der Art, wie das Auftreten und Verhalten der Bewerber*innen und Studierenden eingeordnet wird, zeigt sich eine intransparent geforderte Norm: Bei den Aufnahmegesprächen wird nicht nur die künstlerische Praxis beurteilt, sondern auch die verwendete Sprache, das körperliche Erscheinungsbild, die genannten Referenzen und eine gekonnte Selbstinszenierung. Wer dann nicht den erwarteten Normen entspricht, dem*der wird eine genügende künstlerische Eignung abgesprochen.

Die aufgenommenen Studierenden bekommen diese implizierten Codes weiterhin zu spüren, indem Leistungsdruck, unterschwellige Hierarchien, Abhängigkeiten und unzumutbare aber normalisierte Arbeitsweisen ihren Studienalltag begleiten. Oftmals ist es jedoch schwierig, solche Phänomene zu erkennen oder gar verbal zu kritisieren, wodurch diese Zustände weiter aufrechterhalten bleiben. Darum war es uns im Seminar Eine Krise bekommen – Kunsthochschulen und Ausschlussmechanismen (2022) ein Anliegen, einen Austauschraum für Erfahrungen des Ausschlusses inner- und außerhalb der Institution zu schaffen.

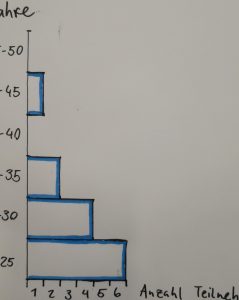

Der Großteil der Seminargruppe, die sich aus Studierenden der verschiedenen Berliner Kunsthochschulen als auch abgelehnten Bewerber*innen zusammengesetzt hat, war vertraut mit den unterschwelligen Codes und Erwartungen der Kunsthochschule und brachte ein großes Interesse mit, diese im Rahmen des Seminars zu hinterfragen. Um einen gemeinsamen Wissenspool zu erarbeiten, haben wir hierfür verschiedene Akteur*innen für Beiträge angefragt, die an Gleichstellungsarbeit, Forschung, studentisch organisierten Support-Strukturen und Aktivismus mitgewirkt haben.

Mit Forough Absalan (Common Ground), ArwinA, Daria Kozlova, Mika Ebbing (Interflugs) und Elena Buscaino (AG Critical Diversity) sprachen wir über die hartnäckige, antirassistische Arbeit studentischer Initiativen und ihre institutionellen Widerstände.²

Sie berichteten uns von der Ignoranz der Institution gegenüber ihren Vorschlägen und von der Gefahr, gleichzeitig für das Image der Universität vereinnahmt zu werden. Mutlu Ergün-Hamaz (Diversitätsbeauftragter der UdK Berlin) betonte in einem partizipativen Diskussionsformat, wie wichtig die Sensibilisierung weißer Hochschulmitglieder und die Stärkung von BIPoC im Studium für die Transformation zu einer diskriminierungssensiblen Institution sei. Seine Stelle als erster – und damit längst überfälliger – Diversitätsbeauftragter ist als Folge auf die Forderungen der studentischen Proteste und Initiativen geschaffen worden.

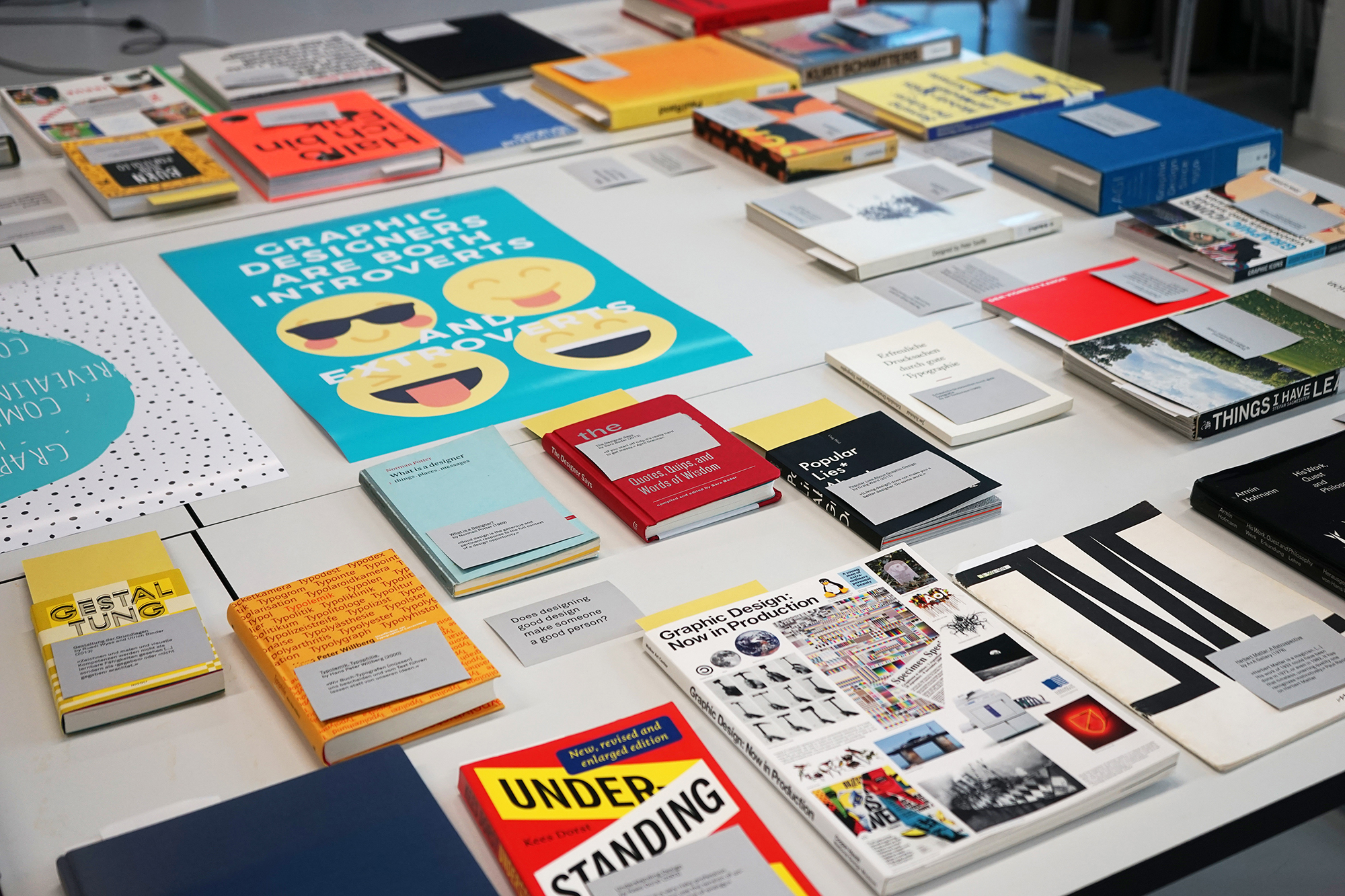

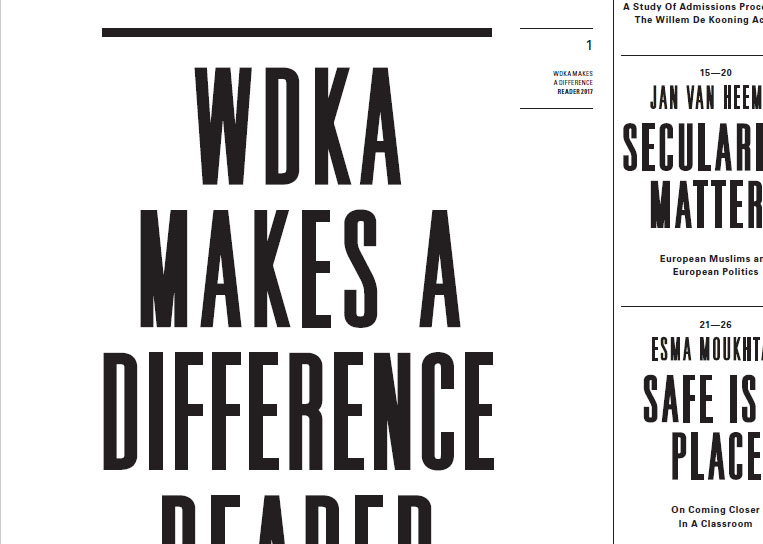

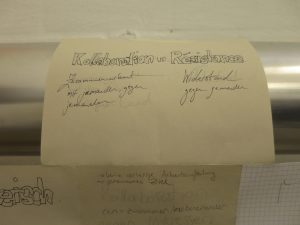

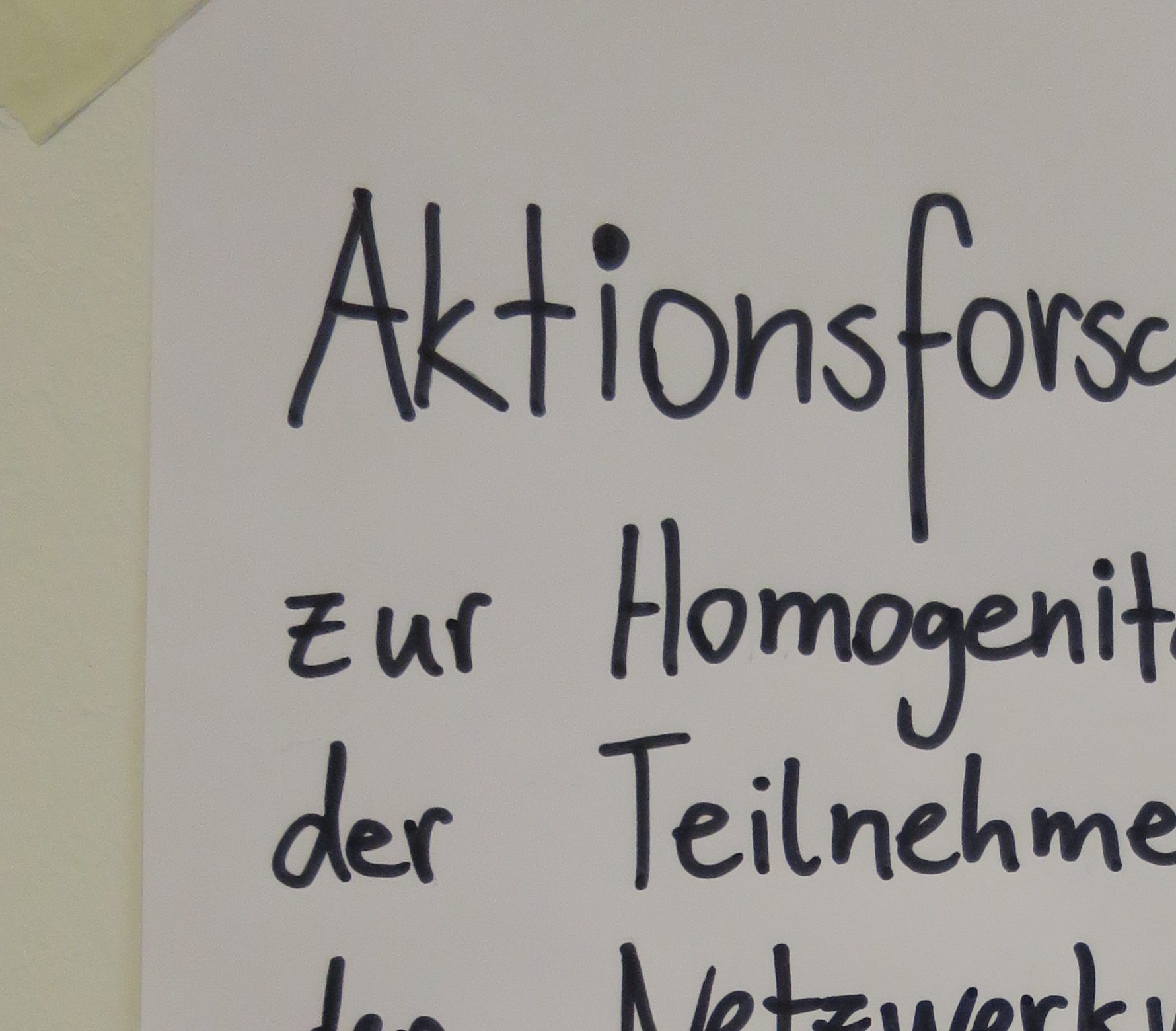

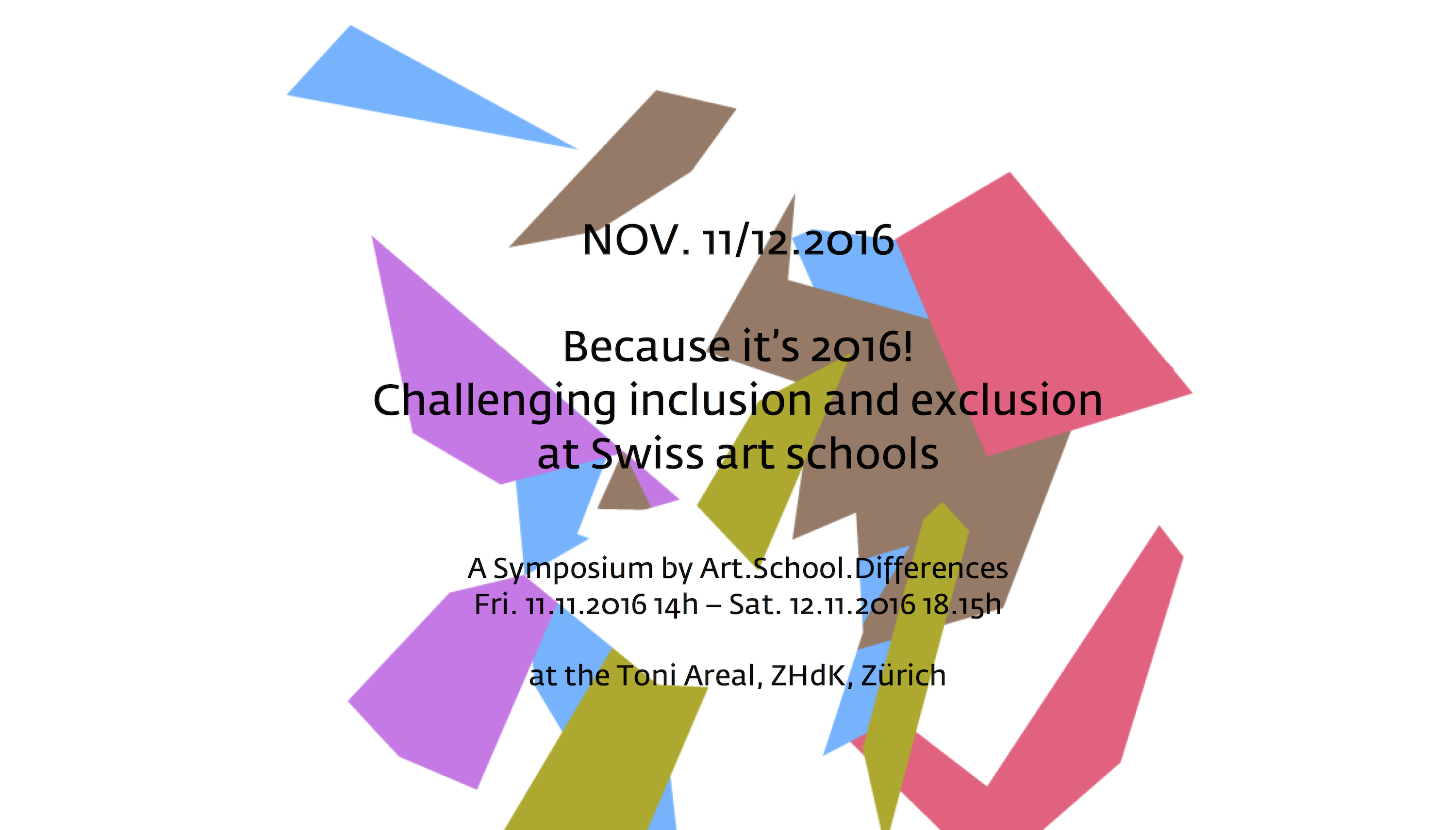

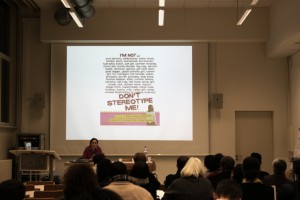

![[Bilder 2 und 3: Hybride Lernsituation während des Vortrags von Sophie Vögele über die Studie Art.School.Differences. Fotos: Eine Krise bekommen]](https://blog.zhdk.ch/artschooldifferences/files/2023/02/P1020205-2-scaled.jpg)

![[Bilder 2 und 3: Hybride Lernsituation während des Vortrags von Sophie Vögele über die Studie Art.School.Differences. Fotos: Eine Krise bekommen]](https://blog.zhdk.ch/artschooldifferences/files/2023/02/P1020213-2-scaled.jpg)

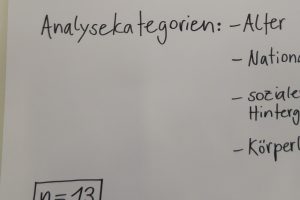

[Bilder 2 und 3: Hybride Lernsituation während des Vortrags von Sophie Vögele über die Studie Art.School.Differences. Fotos: Eine Krise bekommen]

In dem Vortrag von Sophie Vögele (Studie Art.School.Differences) erfuhren wir von Strategien zur Sichtbarmachung von Ausschlüssen durch kritische Forschung mittels Interviews mit Hochschulakteur*innen. Zudem lernten wir das Phänomen des ‚Hot Knowledge‘ kennen, also dem unausgesprochenen, vorausgesetzten Wissen, das durch bereits existierende Kontakte in die Institution und ihr Umfeld zum eigenen Vorteil bei beispielsweise der Bewerbung für ein Studium genutzt werden kann.

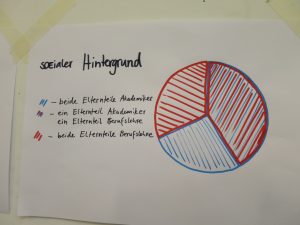

Zusammen konnten wir aufarbeiten, dass sich die Aufnahmeverfahren als zentraler Moment des Ausschlusses herausstellen. Schon in den Aufnahmeprüfungen werden die Bewerbenden auf ihr kulturelles Kapital, Auftreten und ihren soziokulturellen Hintergrund geprüft. Dabei spielt es eine Rolle, die ‚richtigen‘ Referenzen zu kennen, sich gekonnt selbst zu inszenieren und vor allem weiße, elitäre, urbane, eurozentristische Codes zu erfüllen. Dieser bevorteilte Habitus reproduziert bestehende Privilegierungen und ein normatives Konzept von ‚Exzellenz‘. Teil davon ist auch die zumutende Anforderung, das Studium zum uneingeschränkten Lebensmittelpunkt zu machen. Unbeachtet bleiben dabei Sorge- und Lohnarbeit, finanzielle Unsicherheit und geringere körperliche sowie psychische Belastbarkeiten. Entgegen dem Ruf, Kunsthochschulen seien avantgardistische und progressive Orte, wird deutlich, dass sich die Symptome des neoliberalen kapitalistischen Systems im Mikrokosmos der Institution an vielen Stellen wiederfinden und teilweise sogar verstärken.

Um diese Inhalte in eine Seminarstruktur einzubetten und greifbar zu machen, öffneten wir den Raum für unterschiedliche Situationen des Austausches. Ausgehend von den Erfahrungen an Kunsthochschulen, in denen offenbar kaum pädagogische Vorkenntnisse von Dozierenden erwartet werden können, setzten wir den Fokus auf die Konzeption von Methoden, die sich von autoritären Lehrweisen abgrenzen. Selbstorganisierte Seminare bieten daher die Möglichkeit, andere Abläufe zu entwickeln, in denen akademische Codes gemeinsam verlernt werden können.

Kompliziertes Sprechen mit dem Ziel, Anerkennung zu bekommen, wurde beispielsweise mit Methoden wie dem ‚Language L‘ aufgebrochen. Mit der intervenierenden Handgeste in Form des Buchstabens L sollte in Gruppengesprächen von allen auf zu klärende Begriffe hingewiesen werden. So kann ein Raum für Nachfragen zu Unverständlichkeiten entstehen und das Finden einer verständlichen Sprache als gemeinsame Aufgabe begriffen werden – und nicht als Eigenverantwortung von einzelnen Personen. Aber auch andere gängige Verhaltensweisen aus universitären Räumen, wie etwa eine leistungsfähige Selbstinszenierung oder Namedropping, versuchten wir kollektiv zu reflektieren und zu verlernen.

[Bilder 4 und 5: Lockerer Einstieg in die Seminartage mit einem gemeinsamen Abendessen. Fotos: Eine Krise bekommen]

So begann das Seminar für einen lockeren Einstieg mit einem Abendessen, bei dem informelle Gespräche ein erstes Kennenlernen ermöglicht haben. Diese Stimmung bot eine angenehme Grundlage, um im Laufe des Blockseminars auch eigene Erfahrungen mit Zulassungsverfahren zum Schwerpunkt von Gesprächen oder Selbstreflexionen zu machen und diese innerhalb der diskutierten Strukturen zu verorten.

[Bild 6: Gummistiefelspaziergang mit Gesprächsfragen wie „Was hat dich gestern bewegt, überrascht, geärgert, irritiert?“ oder „Was möchtest du in die nächsten Seminartage mitnehmen?“ Foto: Eine Krise bekommen]

In Gummistiefeln spazierte die Seminargruppe durch das Wasserbecken der Floating University und reflektierte dabei die bisherigen Gespräche vom Vortag. Neben den Spaziergängen gab es oft Pausen und Erholungsmomente auf dem Gelände, um den Teilnehmer*innen Rückzug und Freizeit zu ermöglichen. Wir haben zudem versucht, eine Teilnahme durch unterschiedliche Formen von Zuhören, Mitdiskutieren in kleinen und größeren Runden, für sich Schreiben, Lesen und Zeichnen zu ermöglichen.

In mehreren Feedback-Runden gab es die Gelegenheit für die Gruppe, eigene Bedürfnisse zu kommunizieren und diese in die Seminarstruktur einzubringen. Neben einschätzbaren Programmpunkten legten wir Wert auf fluide Zeitpläne, um auf Impulse aus der Gruppe eingehen zu können. Auf Initiative einer teilnehmenden Person konnte so auch ein weiterer Beitrag eingebracht werden: Es gab einen zusätzlichen Vortrag der Student Coalition for Equal Rights, die Ungleichbehandlung von geflüchteten internationalen Studierenden kritisieren und die Sicherstellung von angemessenen, zugänglichen, antidiskriminierenden Studien- und Lebensbedingungen fordern.

[Bilder 7 und 8: Unterschiedliche Lern- und Austauschsituationen während des Blockseminars. Fotos: Eine Krise bekommen]

Zum Teil war es für uns als Organisationsteam in Diskussionsrunden herausfordernd, auf unausgeglichenes Redeverhalten zu reagieren, ohne dabei in traditionelle Moderationsrollen und Gesprächshierarchien zu verfallen. Zudem setzen wir uns in unserer Arbeit immer wieder mit dem Vorhaben auseinander, einen sicheren und sensiblen Raum zum Teilen von persönlichen Erfahrungen zu entwickeln, in dem sich möglichst alle trauen zu sprechen, während gleichzeitig Wert darauf gelegt wurde, Grenzen des Kontextes und der anderen Teilnehmer*innen zu wahren. Nach dem Seminar bemühten wir uns um eine Aufarbeitung, indem Nachgespräche geführt und aufgenommen wurden, um die Erfahrungswerte des Seminars in die zukünftigen Lernformate einzubringen.

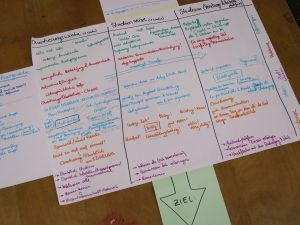

Was bleibt also nach dem Seminar? Es war uns wichtig, die Inhalte des Blockseminars kollektiv zu dokumentieren, um Anderen den Zugang zum erarbeiteten Wissen zu verschaffen. Mit nur zwei Leistungspunkten, die wir für das Blockseminar vergeben konnten, haben wir einander daran erinnert, auf unsere Kapazitäten zu achten und mit realistischen Zielen zu planen. Die gemeinsame Aktion sollte keinen zusätzlichen Druck durch ästhetische Ansprüche oder einen hohen zeitlichen Aufwand erzeugen. Mit dem Wunsch, dennoch mit der herausgearbeiteten Kritik während des UdK-Rundgangs im Sommer 2022 Raum einzunehmen, haben wir eine Diskussion aus dem Seminar aufgenommen und weiterentwickelt.

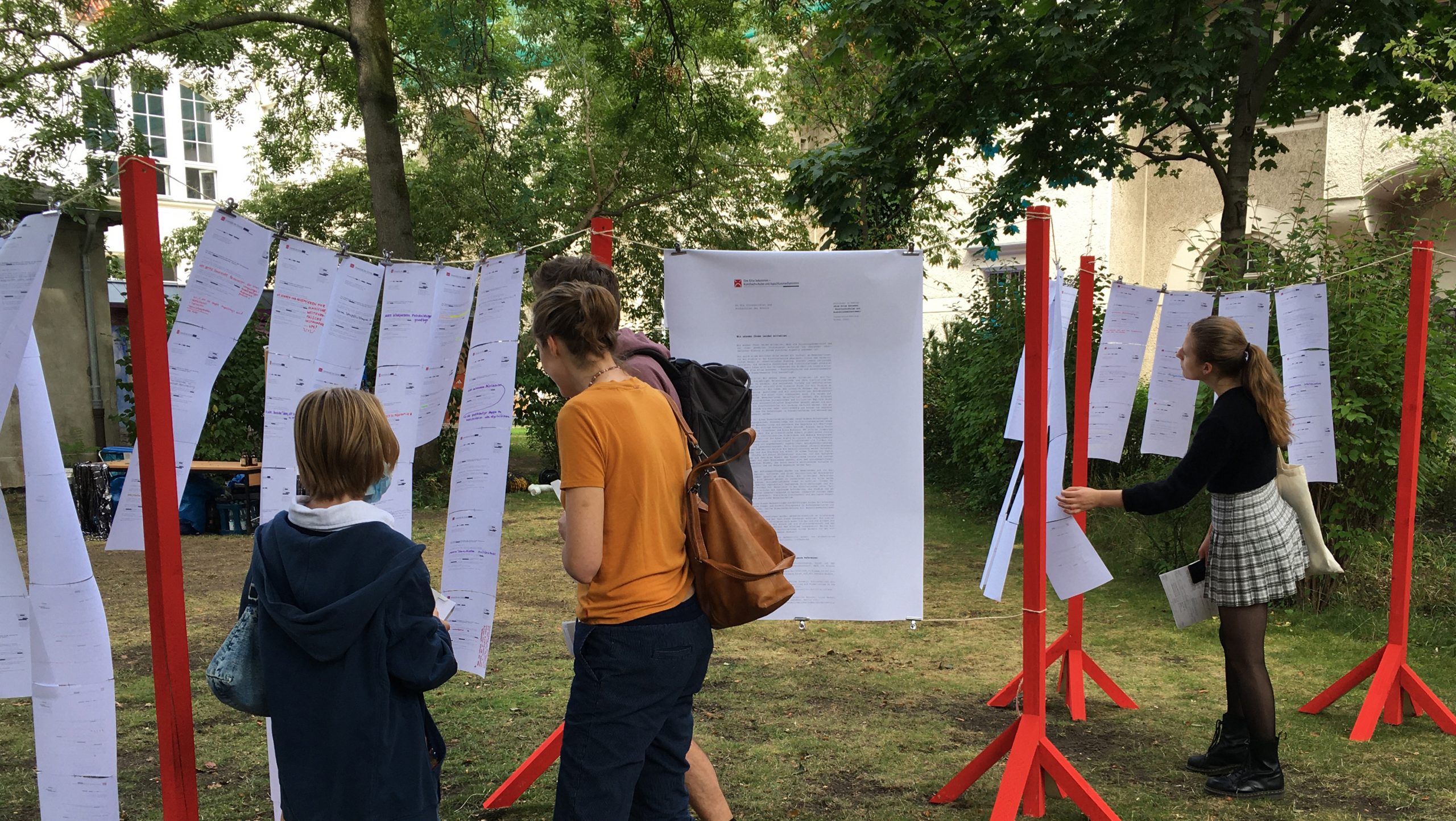

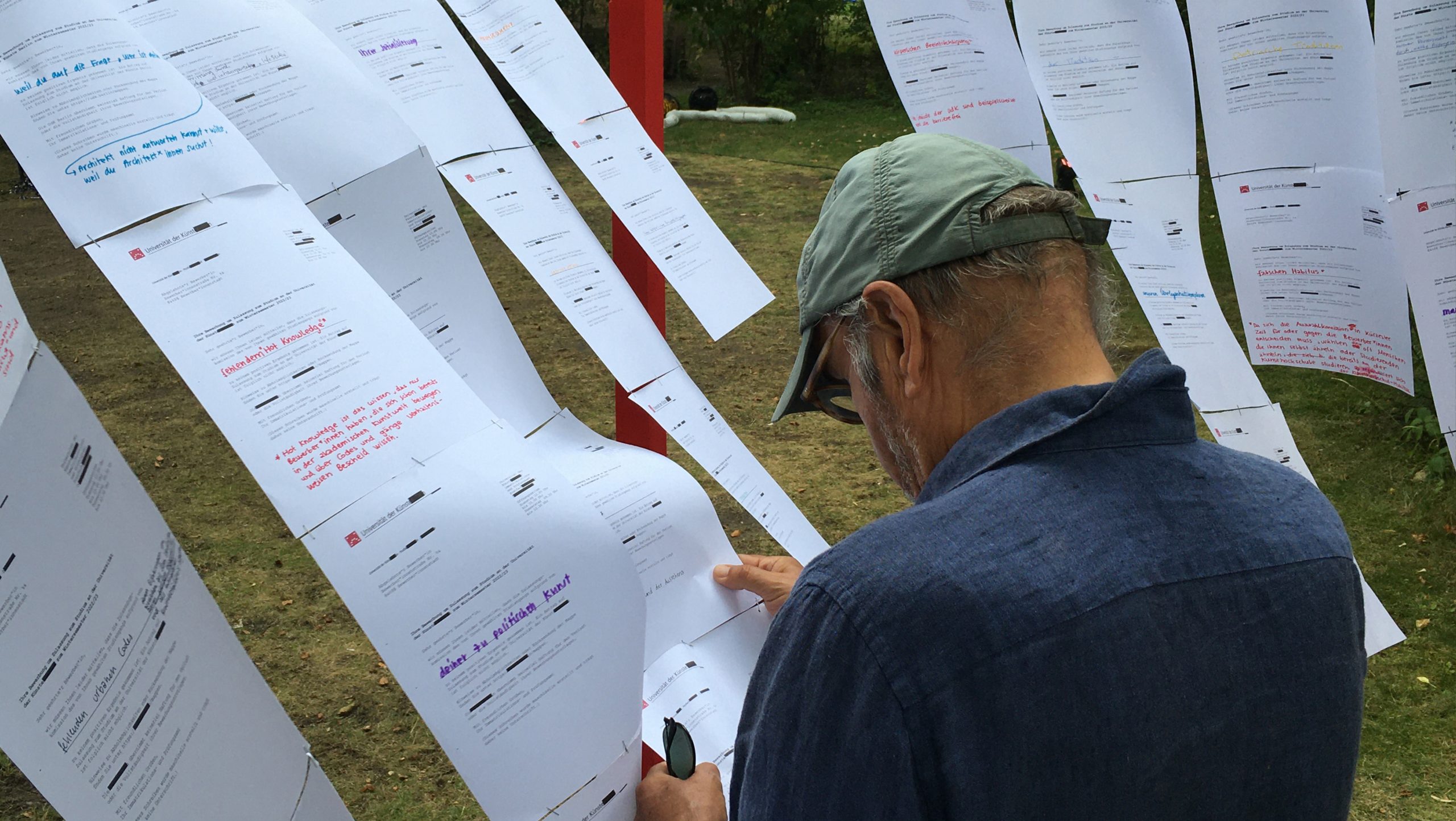

Aus der Zusammenarbeit der Seminargruppe entstand die partizipative Installation „Wir müssen Ihnen leider mitteilen …“ als eine Reaktion auf die jährlich verschickten Ablehnungsbriefe, die in den Postkästen tausender Bewerber*innen landen und ihnen den Zugang zu Kunsthochschulen verwehren. Die eigentlichen Ablehnungsgründe werden in solchen Schreiben nicht ersichtlich und bilden eine unsichtbare Mauer aus Ausschlussmechanismen und Diskriminierungen. Diese undurchdringlich scheinende Wand wollten wir auch mit der Installation räumlich darstellen. Mit dieser Intervention am Image-Event der UdK wurden nun kollektiv Erklärungsversuche gesammelt und eine Kritik an der Institution öffentlich gemacht.

[Bilder 9 bis 11: Installation „Wir müssen Ihnen leider mitteilen, …“ während des UdK-Rundgangs im Juli 2022. Fotos/Bild: Eine Krise bekommen]

Der Grundbaustein dieser Installation ist eine modifizierte Version des Ablehnungsbriefes der UdK, auf dem sonst die niederschmetternden Worte „die erforderliche künstlerische Eignung konnte nicht ausreichend festgestellt werden“ gestrichen und mit einer Leerstelle ersetzt wurden. An dieser Stelle luden wir Besucher*innen des Rundgangs ein, anonym Beobachtungen des Ausschlusses zu formulieren. Es wurden Erfahrungen bei den Aufnahmeverfahren beschrieben oder Analysen der Hochschulstrukturen und ihren Repräsentant*innen benannt. Die modifizierten Ablehnungsbriefe konnten anschließend an eine auf roten Holzstelen gespannte Leine aufgehängt werden. Während des Rundgangs versuchten wir mit der interaktiven Installation vor allem auch abgelehnten Bewerber*innen und damit auch fehlenden Perspektiven, Sichtbarkeit zu schaffen. Auch die zentrale Platzierung der Installation im Innenhof des UdK Hauptgebäudes gab die Möglichkeit, mit unterschiedlichen Personen ins Gespräch zu kommen. Dabei wurde deutlich: Es gibt viele abgelehnte Bewerber*innen und immatrikulierte Studierende, die wütend sind und Redebedarf haben!

„Wir müssen Ihnen leider mitteilen …“ wurde auch Anfang Dezember 2022 während des Aktionstags Recognizing Barriers im Foyer des Hauptgebäudes der UdK Berlin gezeigt. In Gesprächen im Rahmen des Aktionstags kam verstärkter die Frage auf, wie aus einer Institutionskritik auch konkrete Veränderungsvorschläge entstehen können. In Zukunft wollen wir uns als Kollektiv intensiver mit der Frage auseinandersetzen, wie wir Kunsthochschulen und Lehre neu denken können. Diesem Thema wollen wir gemeinsam mit In the Meantime im kommenden Jahr eine Summer School widmen, in der Studierende von verschiedenen Kunsthochschulen kollektiv und experimentell über neue Formen des Lernens nachdenken und utopische alternative Zukünfte entwerfen können. Ein Fokus der Organisationsarbeit liegt dabei auch darauf, wie unsere Arbeit finanziert und die externen Beiträge angemessen honoriert werden können, damit wir die Möglichkeit haben, uns auch längerfristig für zugängliche, multiperspektivische Lernräume einzusetzen.

¹ Die Floating University ist ein selbstorganisierter, interdisziplinärer Austauschort auf dem Regenwasserauffangbecken des ehemaligen Flughafens Tempelhof.

² Siehe Forderungen unter www.exitracismudk.wordpress.com/demands (Letzter Zugriff: 06.02.2023).

Weiterführendes Material:

– Ruth Sonderegger: Doing Class. Hochschulzugang, Kunst und das Gewürz-Andere, Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft. Heft 19: Klasse, 2018

– Beiträge der Plattform Futuress (z.B. Glowing Red Letters, Long Nights, Enough is Enough, Diversity Issues)

– Pierre Bourdieu: Die feinen Unterschiede. Kritik der gesellschaftlichen Urteilskraft, Frankfurt am Main, 1987

* Wer sind wir?

Das Kollektiv Eine Krise bekommen setzt sich kritisch mit der Lehre wie auch den Strukturen der Kunsthochschule auseinander und organisiert dazu Austausch-, Lern- und Aktionsformate. Destina Atasayar, Katharina Brenner, Lu Herbst und Lucie Jo Knilli studierten zusammen im Bachelor Visuelle Kommunikation an der Universität der Künste Berlin, wo sie sich bei der Zusammenarbeit für die Publikation Eine Krise bekommen als Kollektiv zusammenfanden. Im Rahmen des Studium Generale Programms organisierten sie die Blockseminare Eine Krise bekommen – Design und psychische Gesundheit und Eine Krise bekommen – Kunsthochschulen und Ausschlussmechanismen. Das Kollektiv stellte ihre Arbeit in Lesungen, Vorträgen und Workshops unter anderem an der HGB Leipzig, der HTW Berlin und der Muthesius Kunsthochschule Kiel vor.

Destina Atasayar ist Referentin für politische, kultur- und medienpädagogische Bildungsarbeit mit Kindern, Jugendlichen und Erwachsenen. Ihre Themenschwerpunkte sind dabei Antidiskriminierung und Erinnerungskulturen. Derzeit arbeitet sie an der Umgestaltung und Neukonzeption des Lernorts 7xjung.

Katharina Brenner studiert zur Zeit Visuelle Kommunikation an der Kunsthochschule Kassel sowie an der Estonian Academy of the Arts in Tallinn und forscht in ihrem Abschlussprojekt Sharing Knowledge – Students Teaching at Art Universities an dem kritischen Potenzial von studentisch organisierter Lehre.

Lu Herbst studiert derzeit Art in Context (MA) an der UdK Berlin und arbeitet zu den Schwerpunkten Kapitalismuskritik und Kollektivität. Mittels partizipativer Installationen und Aktionsformaten untersucht Lu die (Un-)sichtbarkeiten und Mitgestaltung in öffentlichen Räumen.

Lucie Jo Knilli hat einen Grafik- und Kommunikationsdesign Hintergrund, tauchte während ihres BA-Studiums in die Bereiche Interaction Design und New Media ein und studiert derzeit Gender Studies (MA) in Wien.